Metallic Forest to Ceramic Forest

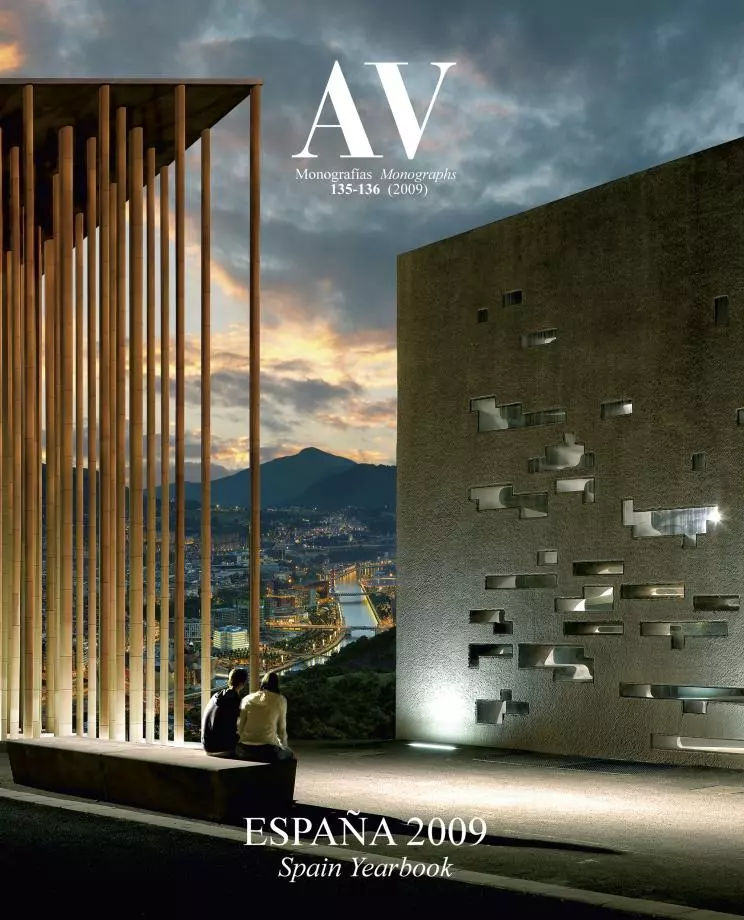

The Spanish Pavilion at the Zaragoza Expo recalls, with its foliage of slender columns, that which represented the country at Brussels in 1958.

Half a century after the Brussels Expo, Hanother Spanish pavilion becomes part of the history of our architecture. In the shadow of the Atomium, José Antonio Corrales and Ramón Vázquez Molezún built a canopy of hexagonal umbrellas on slender shafts, colonizing a park with a luminous, metallic forest that effectively used the ephemeral nature of the pavilion to express the yearning for modernity of a country that was beginning to come out of an economic and social dark age, and that combined the lyrical and mechanical talent of its authors with the organic currents then dominating the international scene. It was a memorable work that marked a turning point in Spanish architecture of Franco times, and its sad reconstruction in Madrid’s Casa de Campo, damaged by time and oblivion, hardly does justice to the splendor of its avant-garde, heroic memory. The original had the laconic austerity of one who avoids excess baggage, freed of historical gravitas by the lightness of its portable design, and the industrial look of those who dream of technique and translate in this code a past of geometric traceries and hypostyle spaces. By the Ebro River, fifty years later, Francisco Mangado’s Spanish Pavilion in Zaragoza’s Expo is a ceramic forest that boldly measures up with its famed predecessor, similarly embracing many contemporary concerns in a happy architectural synthesis.

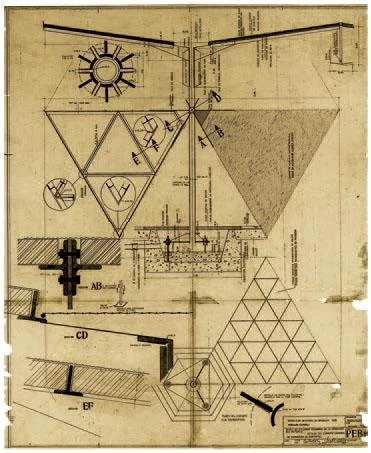

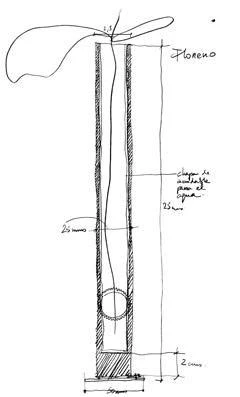

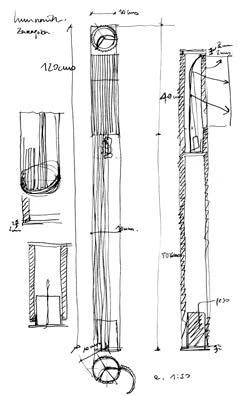

The detail drawing and the period photograph show the great ingenuityof the light ‘umbrellas’.Fifty years separate the delicate hexagonal metal ‘umbrellas’ by Corrales and Molezún at the Expo of Brussels from the dense lattice of ceramic columns surrounding the pavilion by Francisco Mangado at the Expo of Zaragoza.

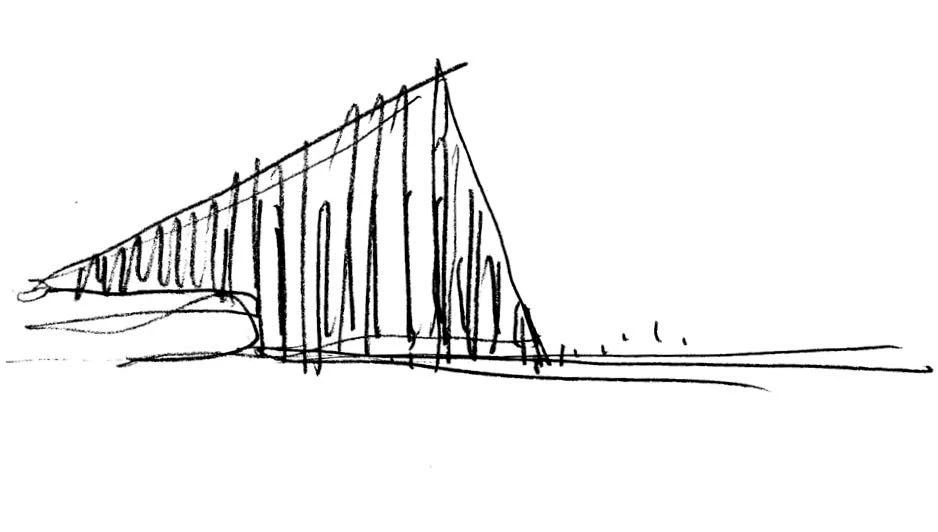

Like all works that transcend their times, the Zaragoza pavilion lends itself to many interpreta-tions, aligning readings that make it part of today’s debates with others of a more timeless nature, and fusing many historic and current references in a syncretic conjunction that rhetoric convention calls polyhedral, but which the composition of the building prompts to describe as fascicular. Whether like facets of a crystallographic solid or like a tight sheaf of fibers, this hank of tangencies is a kaleidoscope pixeled or woven with antithetical elements, which tangle up in ultimately complementary pairs. On one hand, the pavilion joins the duality romanticism/classicism, summed up in the contrast between its most direct metaphors, the essential forest and the classical column. On the other hand, it bridges the opposition of crafts and industry through a building process that goes from the workshops where pieces are designed in dialogue all the way to the site where they are assembled. Finally, it finds a midpoint be-tween representation and abstraction by reconciling the easily recognizable references that Expo visitors demand with the rigorous detailing that marks the work of the Navarrese architect, who, in this work, achieves an exceptional degree of maturity, mastery of craft, and expressive intensity.

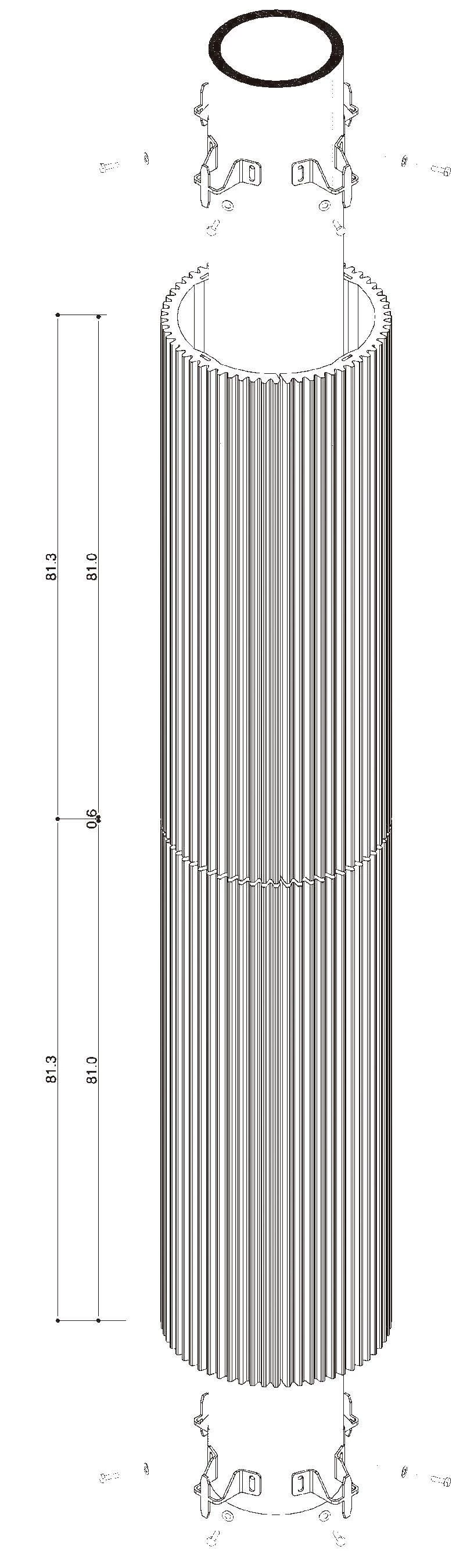

The perimeter columns, with striations that evoke the grooves of classical shafts (also echoed in the merchandising items), filter natural light, buffering direct solar impact in the interior of the Zaragoza pavilion.

Both a peripteral temple and a primitive forest, the pavilion is first of all both culture and nature, reinterpreting the grooved shafts of the classical column with steel cylinders clad with pieces of ceramic that evoke the bark of trees, but whose striations and joints also recall the drums of stone of the most slender Ionic, reconstructing, in passing, the ligneous origin of Greek orders. Classic, therefore, in its dimensional and modular discipline, and romantic in its cluttered profusion of supports, whose ceramic pieces are of different diameters and degrees of firing, the building combines the homogeneous regularity of its 750 soldier-like columns with the picturesque and random variety of their sizes and color tones; the strict order of the subjection to the regular, weightless roof edge with a careful adaptation to the capricious disorder of the site’s topography; and the military reiteration of the palisade of shafts with the triangular and truncated geometry of the perhaps indifferent floor plan.

In the second place, the Zaragoza work brings to a conclusion an exemplary construction process, one where ceramic and metallurgic workshops have collaborated with the architect in designing claddings and frames, spanning the gap between crafts and industry through an assemblage system that fertilizes the vernacular wisdom embedded in the pieces with almost factory-like building methods. Industrial design, a field where Mangado has given many proofs of excellence, in this case joins hands with conventional construction to produce a building whose authorship is both individual and collective, because being orchestrated with violent precision by a demanding director also involves the anonymous or choral knowledge of many craftsmen, and where technical resourcefulness – shown in cases like the cork panels of the ceilings, adapted from those used as insulation in refrigerators –, tries at once to improve the economy of construction and to innovate in stagnant industries.

Finally, the Expo building is faithful to the laconism in detail and the taste for bare matter that distinguishes its architect’s work, but does not hesitate to incorporate the representational and even illusionist features that a pavilion of its kind demands, with that ceramic forest that floats immaterial on a shallow pool, multiplying in reflections and rising amid clouds of water vapor that cool the atmosphere, affirming its identity in a context without qualities – at the start of the process because of a lack of references, and at the end because of an excess thereof – through a foliage of columns, some of which are honestly loadbearing and others not, hiding their scenographic function in the same way that the building’s structural organization conceals its material heterogeneity to put itself at the service of the large spans of the halls. Functional and also spectacular, rigorous and theatrical, abstract and figurative, the pavilion extends the fortunate finding of the grooved ceramic piece through smart, witty merchandising, thus once again linking the productive logic of industrial design with the commercial seduction of emblematic forms.

Just like Molezún and Corrales in Brussels, Mangado in Zaragoza has delivered an efficient representation of the Spain of the times, and if the former Spain dreamt of the modern promises of technology, the latter is a prosperous and satisfied society that recognizes itself in the opulent ele-gance of symbolic language, at once populist and hermetic, with the elementary messages of a fair of smoke and mirrors side by side with archaic references that evoke the isotropic labyrinth of hypostyle space and the warm touch of timeless clay. Temple, mosque or cistern, this forest of columns that rises from the water portrays the fiction of nature with painful lucidity while meekly subjecting itself to the thematic spectacle of the Expo, with the stratifica-tion of intentions displayed by the best architec-ture. This is how the pavilion must be judged in the career of Mangado, who, having turned fifty, now begins a period of assured fertility, endorsed by a work that can measure up with that which half a century ago represented his country in what is now the capital of Europe. Between that metallic forest and this ceramic one, Spain’s political, economic, and social landscape has undergone a historic change, and there is no better representation of this mutation than the architectural voyage charted by these two extraordinary pavilions.