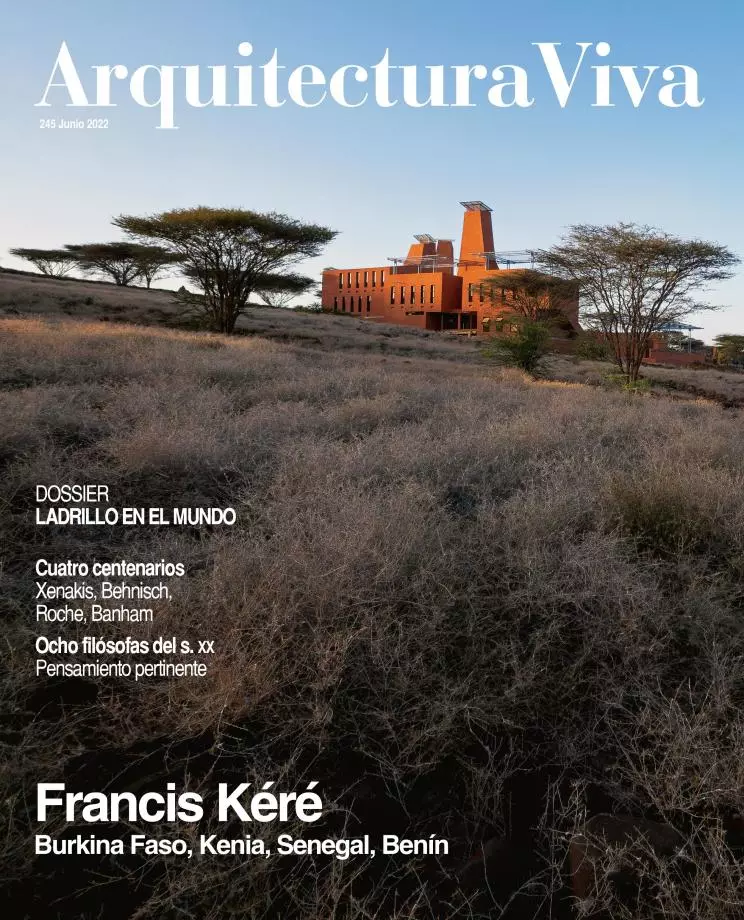

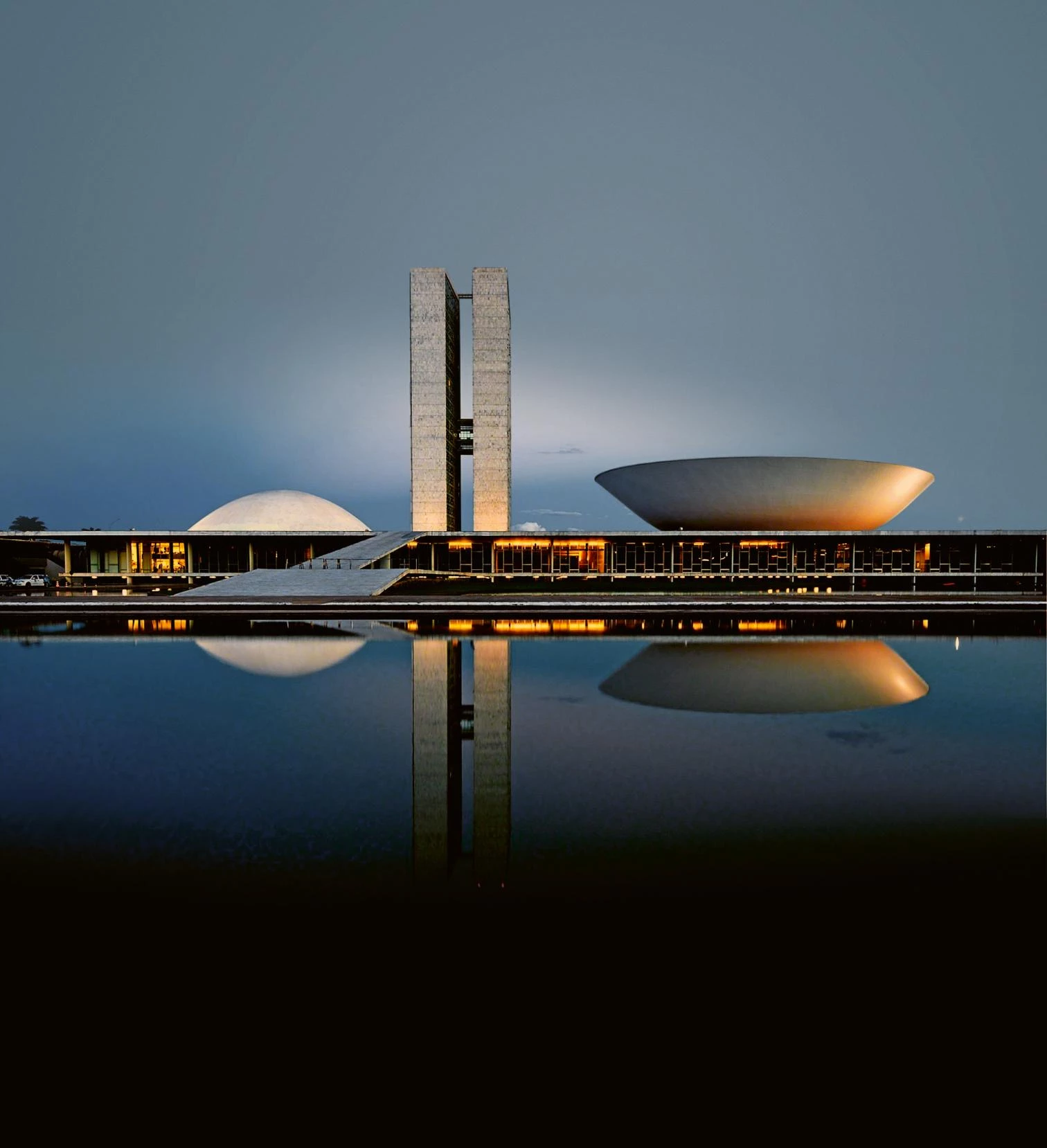

Architecture is not so much ‘frozen music’ as ‘crystallized politics.’ While Goethe understood that it has a mathematical internal order, as music does, its origin and purpose link it to politics inextricably. Organizing the ‘polis’ requires social norms, but also material structures provided by architecture and urban planning. Aristotle’s Politics discusses in detail the ideas set down by Hippodamus of Miletus, who proposed a regular grid as the ideal form for the city, and this connection between geometric order and social order extended with the founding of cities in the classical world, those shaped by the Laws of the Indies in Spanish America and the gridded expansions of the 19th century. From Thomas More to Sinapia – the Spanish utopia attributed to the Enlightenment statesman and writer Pedro Rodríguez de Campomanes – Utopian thought materialized its political ideals in the shaping of the city, and we find the same transference in the case of the French revolutionary architects or the Soviet disurbanists. The new capitals of the 20th century – the Chandigarh of Le Corbusier or the Brasilia of Lúcio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer – arose out of political needs, and at the same time tried to express the nature of the power that created them. The tight marriage between city and politics extends even to the libertarian urge to flee the oppression of the urb, to the sprawl that mistakenly promises individual autonomy, or to the dystopias of today’s literature and film that present social disorganization as urban chaos, and the menace of a totalitarian future of ominously exact metropolises. There can be no politics without a ‘polis,’ nor antipolitics without a negation of the city...[+]