The generic title Alexandrine Years has caused some bewilderment, and I find myself compelled to explain it. On the one hand, it refers to the Alexandrine verse form of fourteen syllables divided into two hemistiches of seven, numbers that matched the fourteen years during which I was in charge of architectural criticism in the newspaper El País, precisely the final seven of the 20th century and the first seven of the 21st. This is not easy to translate, as, for instance, the French Alexandrine only has twelve syllables, but the heptasyllabic matching of the Spanish titles of the two volumes –La edad del espectáculo and Tiempo de incertidumbre – is in continuity with a stubborn determination to use titles of seven syllables, from La quimera moderna, El espacio privado, or El fuego y la memoria to those of my academic investitures, Discurso contra el arte and Arquitectura y vida. This metric preference – used by clerical minstrels, in contrast with the octosyllabic of popular ballads– extends to the hendecasyllabic and obviously the Alexandrine, but is far from the numerological considerations that led Ernst Neufert, for example, to propose a system of Octametric normalization, warning against the use of the number seven, which appears in “many ritual activities, especially in the case of Jews everywhere.”

But beyond these literary ramblings, the term Alexandrine was meant to suggest that our time recalls Alexander’s, a cosmopolitan and individualistic period we have called Hellenistic, with a culture formed – as J.J. Pollitt writes – “by diverse peoples in very distant geographical areas,” and art that has been described as mannerist, baroque, and rococo: far from the restraint of Greek classicism, and in a heterogeneous environment where figures like private clients, collectors, and dealers appear. In tune with the emotional dimension of that artistic output emerges an architecture that is theatrical, often colossal in its pursuit of spectacle, and curiously rigoristic in its pedagogical dissemination of erudite canons. A case in point is Pittheus, who, hating the Doric because of the dimensional problem posed by triglyphs, built strictly modular temples; another is Hermogenes, who created a system of proportional relationships whose prescriptive didactics reach all the way to Vitruvius. In the Roman, incidentally, we find the best anecdote on the meeting of Alexander and Dinocrates, the architect attributed with drawing the regular scheme of Alexandria, but who in order to get the king’s attention disguised himself as Hercules and proposed the visionary project of carving a mountain with his likeness, as would be done 2,300 years later in Mount Rushmore, with the effigies of four American presidents.

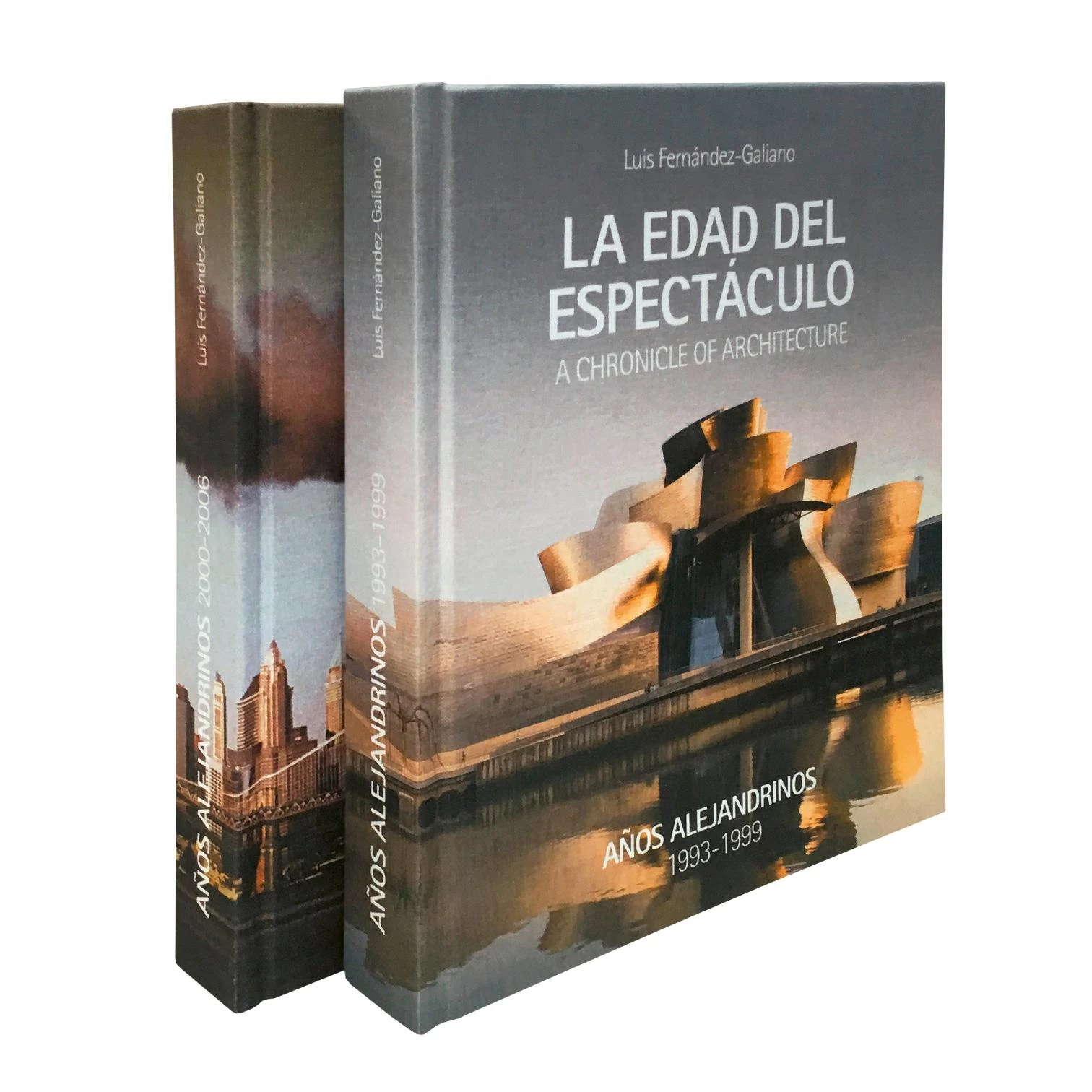

The grid of Alexandria pursues a long tradition, dating as far back at least to 7th century bc, for doling out pieces of land in new colonies, a practice developed two centuries later by Hippodamus of Miletus, an urban planner to whose theories Aristotle devoted several pages of his Politics, summarizing his contributions while also describing him as “a strange man, whose fondness for distinction led him into a general eccentricity of life,” similar perhaps to that of the Dinocrates who would take over the baton from him, or to that of so many contemporary architects. In the rarefied and erudite environment of the Library of Alexandria, the poet Callimachus – not to be confused with the sculptor of two centuries before, traditionally considered the inventor of the Corinthian order – censured a work of his rival Appolonius of Rhodes with an epithet that has gone down in history: mega biblion, mega kakon, “big book, big evil.” The two heavy volumes of Años alejandrinos perhaps deserve this jibe, because in the end, in their cosmopolitan colossalism, obsessive geometry, and visual drama, they are in themselves mannerist, Alexandrine like us all.