Buildings for Music Since 1950

Acoustic Traces

Hans Scharoun, Philharmonie, Berlin (1963)

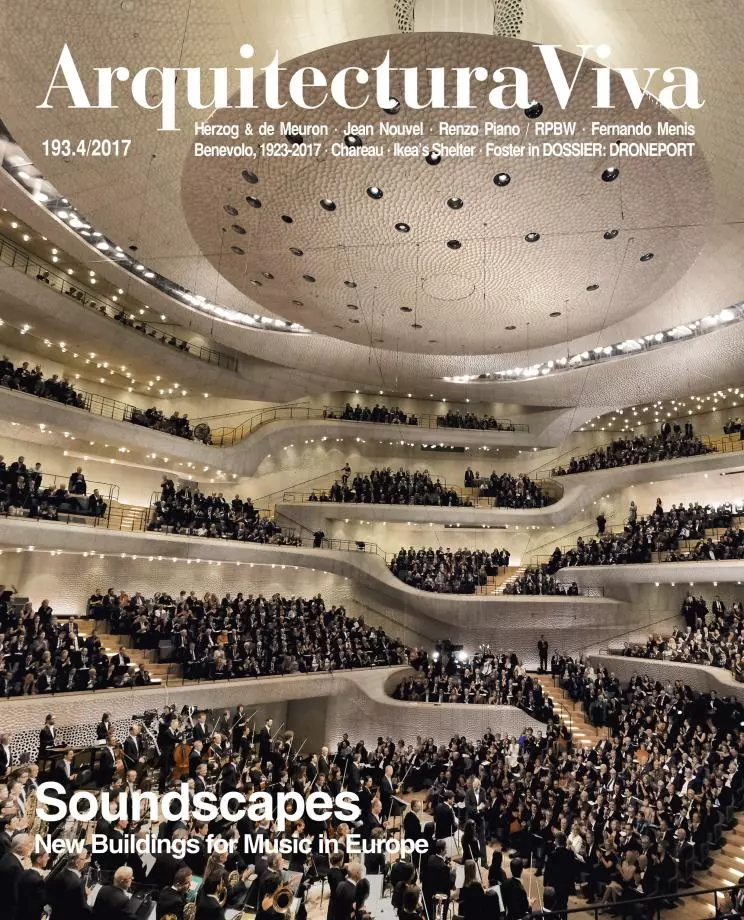

Between the opening in January 2015 of the Philharmonie de Paris, a work of Jean Nouvel, and the much-awaited inauguration in January 2017 of the Elbphilharmonie of Hamburg, designed by Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron (see Arquitectura Viva 191 and 192), the polemic unleashed by Sir Simon Rattle, the new director of the London Symphony, asking for a new concert hall for London, only goes to show how European capitals are interested in maintaining their leadership in the musical world, in a panorama that demonstrates a lack of harmony with the youngest audiences and which seems to be clamoring for different kinds of spaces for the latest in music.

This growing interest led to the contemplation of the new concert halls – most of them conceived in the manner of Scharoun’s Berliner Philharmonie, with the stands, like terraces or vineyards, embracing the stage – as just another step in the search for the ideal musical space, but also as the consolidation of a specific building type in the city. A search that has been anticipated in some built cases in the course of the 20th century in Europe and the United States, whose influence impregnates the new generation of auditoriums in Europe and also the numerous ones now springing up in exotic Eastern places which until a few years ago were distanced from musical traditions of the West.

If the 20th century started with the 1900 dedication of the first ‘technological’ concert hall, the Symphony Hall of Boston, the 21st century took off in 2003 with the sophisticated Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, whose success lay in combining a dazzling image with the reliability of a sound system entrusted to the acoustic engineer Yasuhisa Toyota, who is, after all, responsible for the sound excellence of the major auditoriums of the last decades, from Suntory Hall in Tokyo (1986) by Shin Miyake and Shoichi Sano, the Nagaoka Lyric Hall (1996) by Toyo Ito, and the Danish Radio Concert Hall in Copenhagen (2009) by Jean Nouvel to the Philharmonie de Paris (2015) by Jean Nouvel again and the already mentioned Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg (2017) by Herzog & de Meuron. Clearly there is continued confidence in the power of grand auditoriums to transform the city and rejuvenate music, and live up to expectations of a monumental image, maximum acoustic quality, and the right atmosphere for musical life, as expressed in the brief of the current competition for the future Konzerthaus of Munich, a city of strong ties to music that has been losing its philharmonic protagonism.

To address such requirements, one has to understand that the very idea of an auditorium entails, on one hand, remembering all the different places, open-air and enclosed, where music has been performed through the ages, and on the other hand, considering the fact that people who go to a performance, without giving up individualities, become a single audience participating in a transcendental event. Unity and individuality together take part in a special ritual of absorption that once could also be found in nature, which reminds us that the first places for music were neither inside a building nor inside the city.

Short History of the Auditorium

To understand the current music-performance building, it can help to look at previous cases which introduced aspects still seen in auditoriums: the Royal Festival Hall of London (1951) by Robert Matthew and Leslie Martin, the Kresge Auditorim at MIT in Cambridge (1955) by Eero Saarinen, the Kulttuuritalo of Helsinki (1958) by Alvar Aalto, and the Berliner Philharmonie (1963) by Hans Scharoun. All were built in the years following World War II, and expressed impulses that explain their urban and social importance. They burst onto the scene charged with novelty and surprise, criticizing modern architecture of prewar decades and setting a new way for music buildings to engage with their cities.

The Royal Festival Hall is a functionalist building whose volume clearly expresses its internal layout, much marked by the transparency of the foyers, which give continuity to the exterior platforms that stretch towards the Thames, where the BBC Proms (summer season of daily orchestral classical music concerts, and therefore informal outdoor-related music-listening), take on new meaning. Its contribution lies in the autonomy of foyers thought out as spaces with a life of their own, used all day as a venue for exhibitions, matinée concerts, and jazz gigs, mixed with the activity of shops and bookstores, restaurants and cafés; a mix of activities that ultimately turns the tiered foyers into a continuation of the terraces of the Thames, a precursor, thus, of other informal spaces for musical happenings, and giving London one of its most popular and open public spaces.

The concert hall is rectangular in plan and the longitudinal section shows three areas – orchestra (musicians and public), terrace, and balcony – arranged under a continuous, trumpet-shaped ceiling, a descendant of the one that Gustave Lyon used in the Salle Pleyel in Paris, which in the music world would come to be as prestigious as Pleyel pianos, built in 1927 to become the music center of the French capital, a status it maintained until the recent inauguration of the new Philharmonie at the Cité de la Musique came with a governmental decree against including classical music in its programming.

A few years after the inauguration of the Royal Festival Hall, the Kresge Auditorium in Boston opened its doors with the aim of serving as a “meeting place for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.” On a circular platform, slightly elevated, rises a self-withdrawn form, a spherical cupola triangular in plan, resting only on the triangle’s three vertices, which in turn produces three elevations of slightly curving glazed arches. Present in the spherical membrane of the Kresge Auditorium is the large tent in the landscape of Aspen, and the work marked the start of a new path in the career of Saarinen, who defined his architecture by linking architectural form to a wider context of thought. In this context, form was seen by Saarinen as an expression of his humanistic conception of life, a conception where geometry is attributed with a capacity to create a unity that is spatial, structural, and conceptual at the same time. Inside, Saarinen sought to reduce the structural complexity of the roof to a single basic stand. The entire audience is accommodated in its variable slope, under a roof that wishes to disappear as if it were the vault of heaven. There are no balconies and no boxes, just some white reflectors floating over the audience and orchestra, hanging from the vault, like clouds necessary to counter the effects of the sphere’s concavity, which is inevitably bad for sound.

If in 1950s and 1960s social-democratic Europe most auditoriums built were rationalist, medium-sized, and acoustically different from theaters, Alvar Aalto’s expressive work opposed this tendency. His numerous projects for theaters, cultural centers, and auditoriums are so outstanding in quality and aesthetic power that they became permanent references for architects designing concert halls.

In 1958, on a street on the outskirts of Helsinki appeared the solid and sinuous volume of reddish brick of the concert hall of the Kulttuuritalo. In this strange form rests all the building’s power to surprise, but paradoxically the interior harbors a hall of amiable geometry, and this explains the enduring lure of a unique construction whose bold volume seems to belong more to the rocky hill on which it stands than to the urban fabric. The hall’s floor plan deforms the fan geometry, making it asymmetrical, and this is typical in the Aaltian repertoire, which always preferred it to the more conventional schemes, which were rectangular, deep, and frontal with respect to the audience.

Scharoun’s Philharmonie

In 1956, while the House of Culture in Helsinki was going up, a competition was organized in Berlin for the purpose of making a home for the Berliner Philharmonie, whose original building was destroyed in 1944, with the rest of the city. The jury, after positively judging the visual impression of the hall and the advantages of making the audience surround the stage, declared Hans Scharoun’s entry the winner, highlighting that the shape of the ceiling, resembling a camping tent built in Aspen, Colorado, would help ensure good acoustics. The building’s unique image is to a large extent due to the extraordinary historical and political momentum then being lived by its city: a Berlin tormented by the construction of the Wall, just when it seemed in for an economic takeoff, while experiencing a climate of renewal in art and music, a heyday of randomness and informality, and also the end of the avant-gardes.

Add to all this the needs of an exceptional philharmonic orchestra, the demands of an audience with a firm musical tradition, and the personality of the Berliner Philharmonie’s erstwhile principal conductor, Herbert von Karajan. All this seemed to happily coincide with the interests that pulsated in Scharoun’s architecture, and they crystallized in the Philharmonie: a new kind of musical and also social space, the inventiveness of which deserves acknowledgment as a new architectural type. The model of the competition entry was already clear about the choice of topography for the music space. It also showed the position of people: the director and musicians at the center; the audience around them, arranged not symmetrically but mostly right before the stage; and the rest in groups of tiers on the sides. Because of the position of the box and organ, the asymmetry is more pronounced behind the choir.

Auditoriums come from other typologies, but here is a new one with the capacity to evoke nature without resorting to literal mimicry, using poetic images instead: Scharoun’s valley of vineyard terraces, the eroded rock that Alvar Aalto left as if by accident in the Helsinki topography, the lightweight blue sphere that Saarinen placed over the rows of seats in the Kresge Auditorium, or the river terraces sliding into a diaphanous space of platforms that Leslie Martin opened on to the Thames. Each of them stands out in its city.

In the making of musical spaces, forms and materials are definitely determinant. They are what make the space ‘sound.’ But it is still people who give the space wholeness and social intensity, to the extent that in gathering in the auditorium, they express the need for union that pulsates in the music itself. The architect has to delve into that need before drawing the plans of the musical space. Architects have to do this if they wish it felt that the auditorium is really a mechanism endowed with the capacity to ‘transport’ us, without moving us from the city we live in, to a faraway open-air nature that already exists only in our imagination.

Ignacio G. Pedrosa is the author of the Ph.D. dissertation ‘Auditorium: a 20th-century Typology.’