Babel vs. Babylon

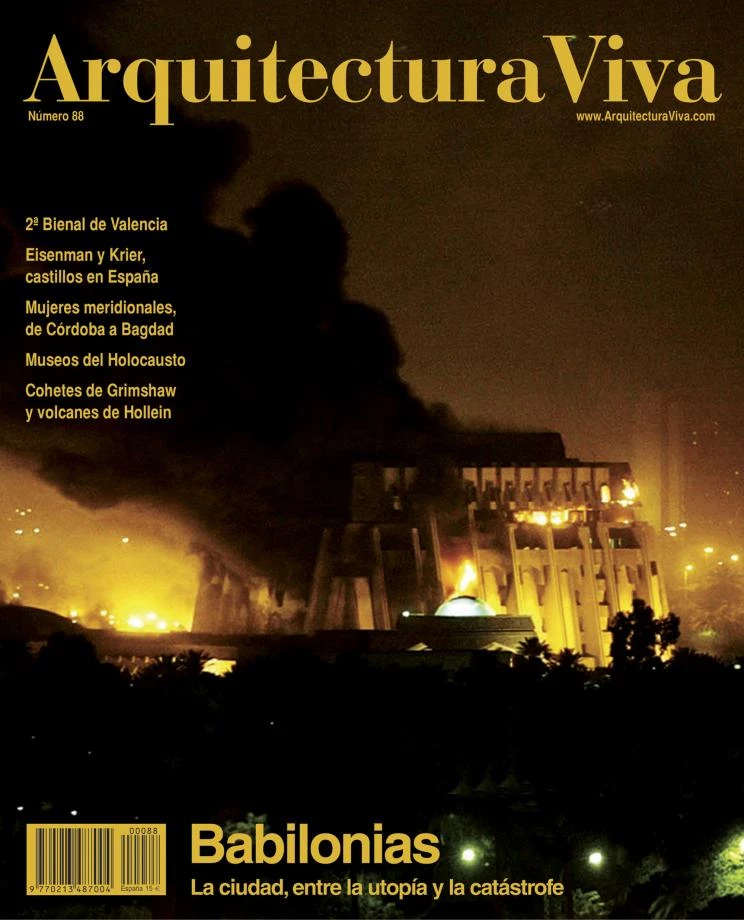

The Iraqi conflict has a symbolic dimension: the monuments of the Arab world clash head on with the built emblems of American democracy.

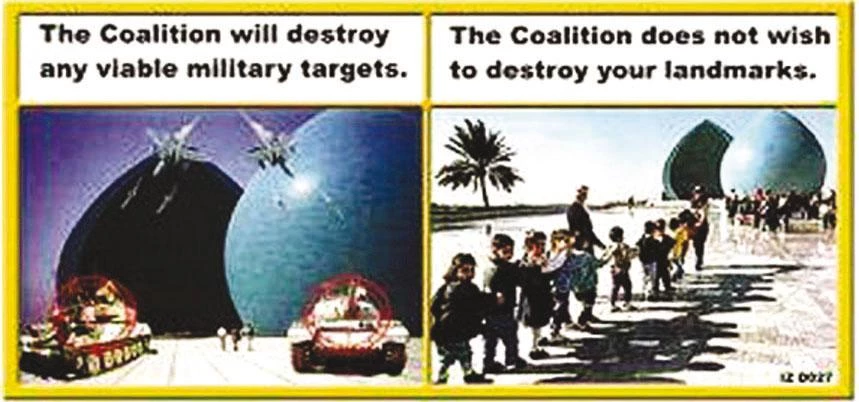

Wars destroy individual lives and collective symbols in equal parts. In the conflict that is closing in on the Near East, the terrible threat of urban bombings is cynically softened with the promise to respect the despot’s monuments, but the victims of this wave of violence will find little consolation in such sparing of architectures. If there is an architecture that deserves respect, it is the architecture of the city, that formidable human creation that has traveled in time from the Fertile Crescent all the way to the Manhattan Babel where Baghdad’s future is being dealt these days. After a century of colossal urban holocausts, the empire should not taint the dawn of the third millennium with the crepuscular fire and blood of an urbicide in Babylon. According to the American media, the Pentagon’s plan is to launch more cruiser missiles on the first day of battle than were used in the forty days of the Gulf War of 1991, following a strategic concept baptized as “Shock and Awe” whose objective is to annihilate the enemy’s will to fight in one stroke, through a sudden devastation resembling Hiroshima. With the prospect of an anonymous apocalypse, the innumerable casualties of which would be concealed under the pious denomination of “collateral damage”, the canonizing of architectural landmarks by the pamphletsof the so-called Coalition is intolerable: it is as if the megalomaniac monuments of an Asian satrap deserved more respect than the vulnerable lives of so many people.

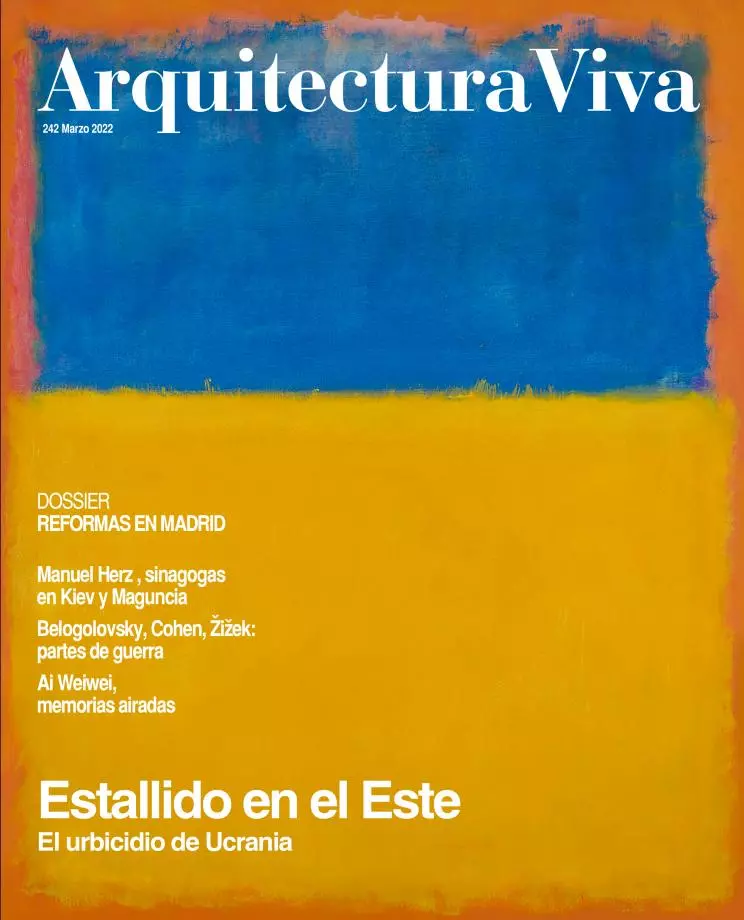

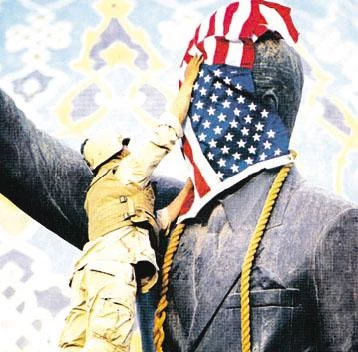

No one – and much less the politician – can ignore the muscular power of symbols. But when the inanimate emblem takes priority over human life, a heinous crime implants itself in the gaze that judges the world and the hand that acts upon it. In a recording broadcasted by Qatar’s TV channel Al Jazeera shortly before the U.N. Security Council session on Valentine’s Day, a voice claimed to be Osama bin Laden’s once again celebrated the destruction on that September 11 of the “idols of the American infidel,” presenting the extermination of thousands of persons as the mere elimination of a symbol. However, the architects who have these past months presented proposals for the replacement of the Twin Towers – on a site which was immediately given the name used to indicate the epicenter of a nuclear explosion, Ground Zero – have seen for themselves how this devastated plot cannot call itself the defiant seat of the USA’s economic power, nor the inevitable memorial of a young empire’s wounded pride, without simultaneously acknowledging its sorrowful status as a unanimous cemetery. After the trauma of 9-11, the federal government set about thoroughly documenting three other national icons – the Statue of Liberty, the Capitol dome and the presidential busts of Mount Rushmore – to facilitate reconstruction in case of terrorist attacks on them, and it is obviously the same kind of candid obsession with symbols that underlies the disconcerting concern for Saddam Hussein’s monuments in Irak.

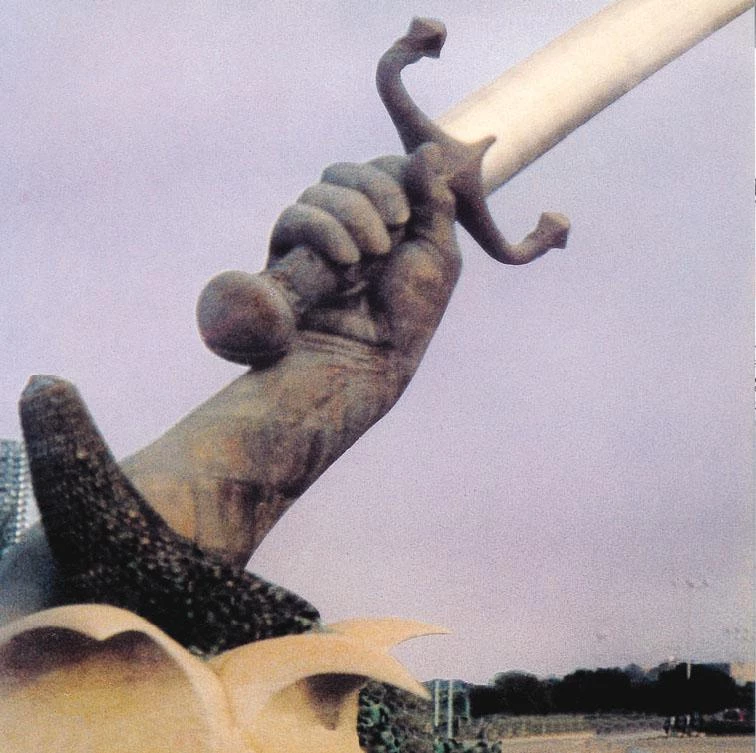

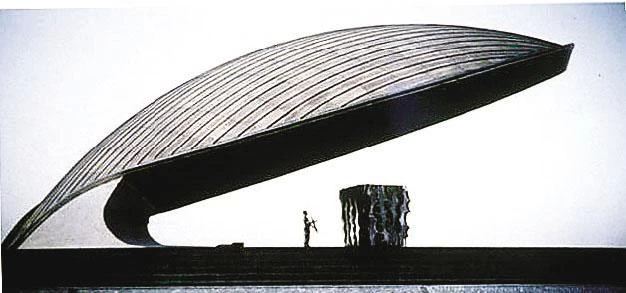

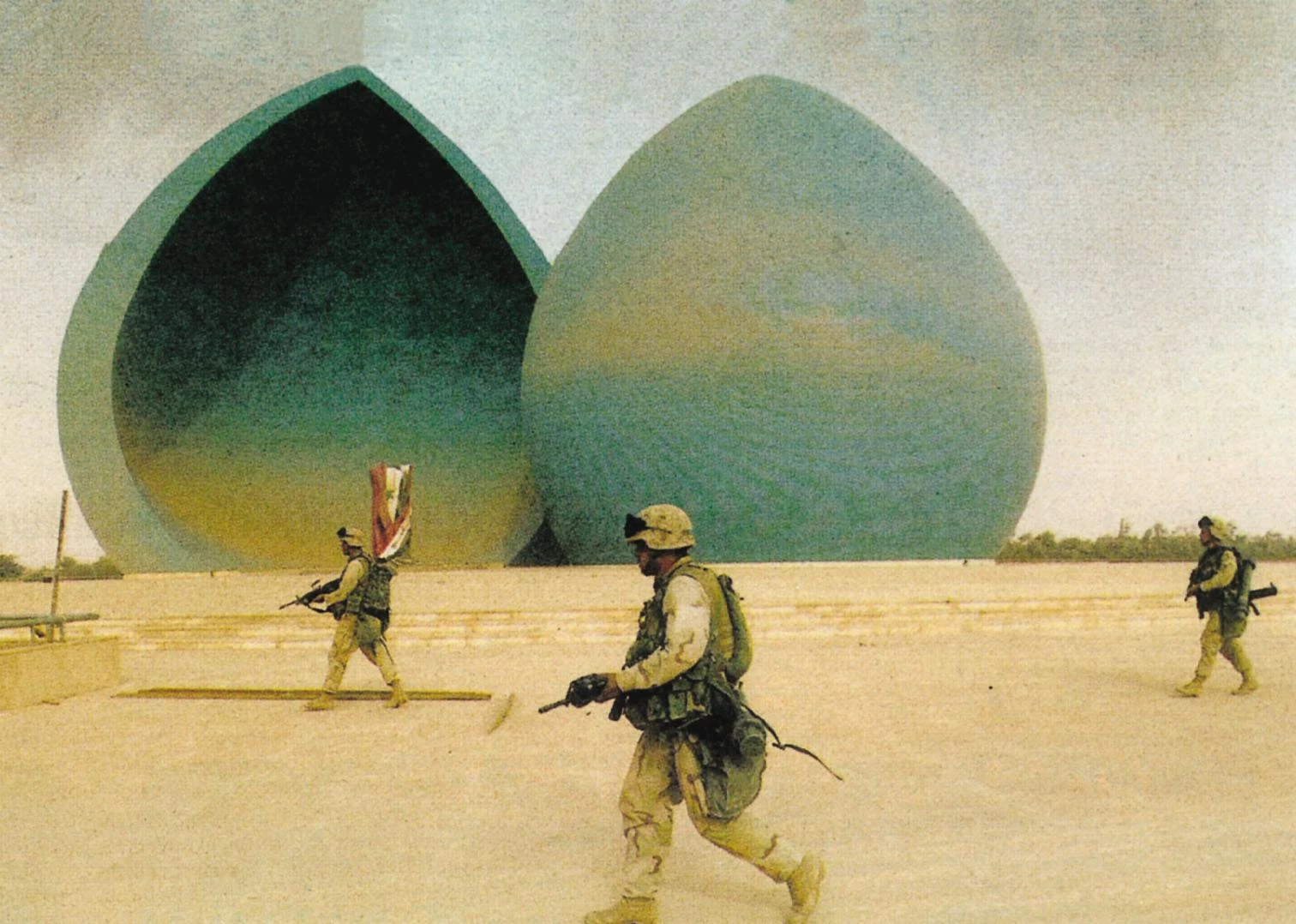

As grandiloquent as Saddam’s regime are its monuments: the Shaheed, devoted to the martyrs (below); that of the Unknown Soldier (above); and the Arch of Victory (above), raised after the war against Iran.

The most representative constructions of the Baathist regime commemorate the war with Iran and frame the ceremonial spaces of Baghdad. The Shaheed or Martyrs’ Monument – initiated in April 1981, a few months after the start of the protracted conflict with Iran, and finished in 1983 – is formed by two halves of a sectioned dome; clad with tiles of a turquoise color, its onion shape evokes the cupolas of mosques. A work of the sculptor Ismail Fattah al Turk with the engineers of Ove Arup (the same firm that had managed to raise the colossal shells of the Sydney Opera House ten years before), the dome with a 40-meter diameter was built with a cost of 250 million euros in the middle of a manmade lake, and its titanic combination of vernacular representation and à la Kapoor abstraction has since then fascinated numerous visitors. Chosen by American pamphlets as Iraq’s most characteristic monument, on February 16 (the day after the massive anti-war demonstrations worldwide) it again made the headlines as the scene of a parade celebrating the anniversary of the so called massacre of Al Amirya, a refuge in Baghdad where 400 civilians perished during the first Gulf War. Almost at the same time as the Shaheed, and also surrounded by a large artificial landscape, rose Saddam’s second emblematic project, a Monument to the Unknown Soldier that combines a gigantic slanting disc – inspired by a traditional shield but closer to a flying saucer or a giant clam – with a futuristic ziggurat that is a reinterpretation of Samarra’s famous minaret.

American soldiers in front of the Martyrs Monument in Baghdad

Appealing to the symbols of national identity, the United States has used the same iconography as its enemies, as can be seen in the North Korean propaganda poster and in the pamphlets addressed to the Iraqi people. The latter cautioned that the bombings would not destroy collective symbols, though the images of US troops in monumental sites bear witness to the actual seizure of the country.

Conceived in 1985 and built after the end of the war with Iran in 1988, the Arch of Victory is the third of Saddam’s great monuments and completes the dictator’s program of urban icons. Formed by two pairs of swords that meet forty meters above a broad avenue, the double arch marks the far ends of a processional axis, on one side of which rises a grandstand crowned by an enormous canopy resembling a shell. The swords refer to the Arabian leader who defeated the Persians in the year 637, making way for the Islamization of Iran, and the fists that brandish them are supposed to be modeled on Saddam’s own hands. Scene of the regime’s most spectacular ceremonies, the nocturnal images of the parades with fireworks recall the mass rallies of Nazi Germany, but with a kitsch touch of postmodern representation: “a combination of Nuremberg and Las Vegas,” in the words of Kanan Makiya, the exiled dissident who in 1991 published, under the pseudonym Samir al Khalil, an abrasive book about this unique monument, at once totalitarian and pop. In his memoirs, published the year after, General Schwarzkopf mentioned having suggested to Colin Powell that it be blown up: “to my surprise, Powell was all for it, although he suggested we check with the President first, and a couple of days later Pentagon lawyers vetoed the idea.”

Saddam Hussein, fond as he is of monumental architecture, does not seem to share such scruples when it comes to breaking the symbolic spine of his enemies. On February 27, 1991, withdrawing from Kuwait, the Iraqi forces burned down the National Assembly building, a masterwork of the Danish architect Jørn Utzon that had been inaugurated only a few months before, and which HOK subsequently reconstructed at a cost exceeding 70 million euros. In spite of the fictitious nature of the Kuwaiti democracy – an ephemeral parliament of dignitaries, in a country where most of the population lacks citizenship and where women still do not have suffrage – Utzon’s orderly labyrinth and concrete canvases were a sign of hope that Saddam’s troops did not hes-itate to destroy, moved by the same hostility that North Korean propaganda shows when it places the emblems of American democracy as the target of their missiles. It is likely that the fourth airplane of 9-11 was headed for the Capitol, and this Islamic aggression would have been more real a threat than the irate messages of Pyongyang posters. But Saddam is neither Osama bin Laden nor Kim Jong II: his military dictatorship is far from religious fundamentalism, no matter how much his ambassador to the U.N. ritually begins his speeches by invoking Allah; and his crumbling cruel regime simply does not have the nuclear weapons with which Korea’s deified lunatic has been regularly threatening the US and his own neighbors, however much his stubborn resistance to disarmament is succeeding to divide the EU and NATO as the very real risk of nuclear proliferation has never done before. Impoverished and exhausted, the people of Iraq do not deserve to star in the last chapter of what W.G. Sebald called the “natural history of destruction.” In the end, the symbols of American democracy are ours too, and the Empire does not need to assert its strength by chastising the wretched paradise of Baghdad with a thousand and one nights of pain.