Evoking the events

Seville Expo, Barcelona Games

With the Seville Expo and the Olympic Games of Barcelona, Spain lived in 1992 an annus mirabilis. Twenty-five years later, the two cities have commemorated this anniversary with a crop of exhibitions and events. And yet, while the celebrations of the Expo have had a negligible impact beyond the Andalusian capital, everything that has been organized to remember the Olympic Games has had huge media coverage, no doubt owing to the coincidence with the secessionist challenge of the Catalan government, which has encouraged stressing the fervor of the organizational and sports successes that braided Barcelona’s splendor with Spain’s pride. The boost of self-esteem was also economic, and the large investment in both cities made it possible to renew their urban fabric with infrastructures and buildings. In the end, the fiestas of Seville and Barcelona were also fiestas of architecture, and both AV Monographs and Arquitectura Viva dedicated issues to the works and projects in both cities, documenting the constructions that went up for the events and offering an early assessment of the transformations. Joining the celebration of the anniversary of that magical moment for the country, our website has recalled the chronicle of the inauguration ceremony of the Games, which Luis Fernández-Galiano published in El País under the title ‘La soledad del arquero’ (The Loneliness of the Archer), and the following pages reprint the introductory texts of the AV monographs devoted to the Seville Expo and to Olympic Barcelona. In both cases, the presentation has an oxymoronic tone that ravels praise and caution: in Seville, combining futuristic silicon with media silicone; and in Barcelona, bringing foolhardy Icarus face to face with hospitable Icarius. A quarter of a century later, and dramatically coinciding with the terrorist attack on Barcelona’s Rambla, it is perhaps fitting to remember that moment of joy.

Silicon and Silicone

Seville Expo

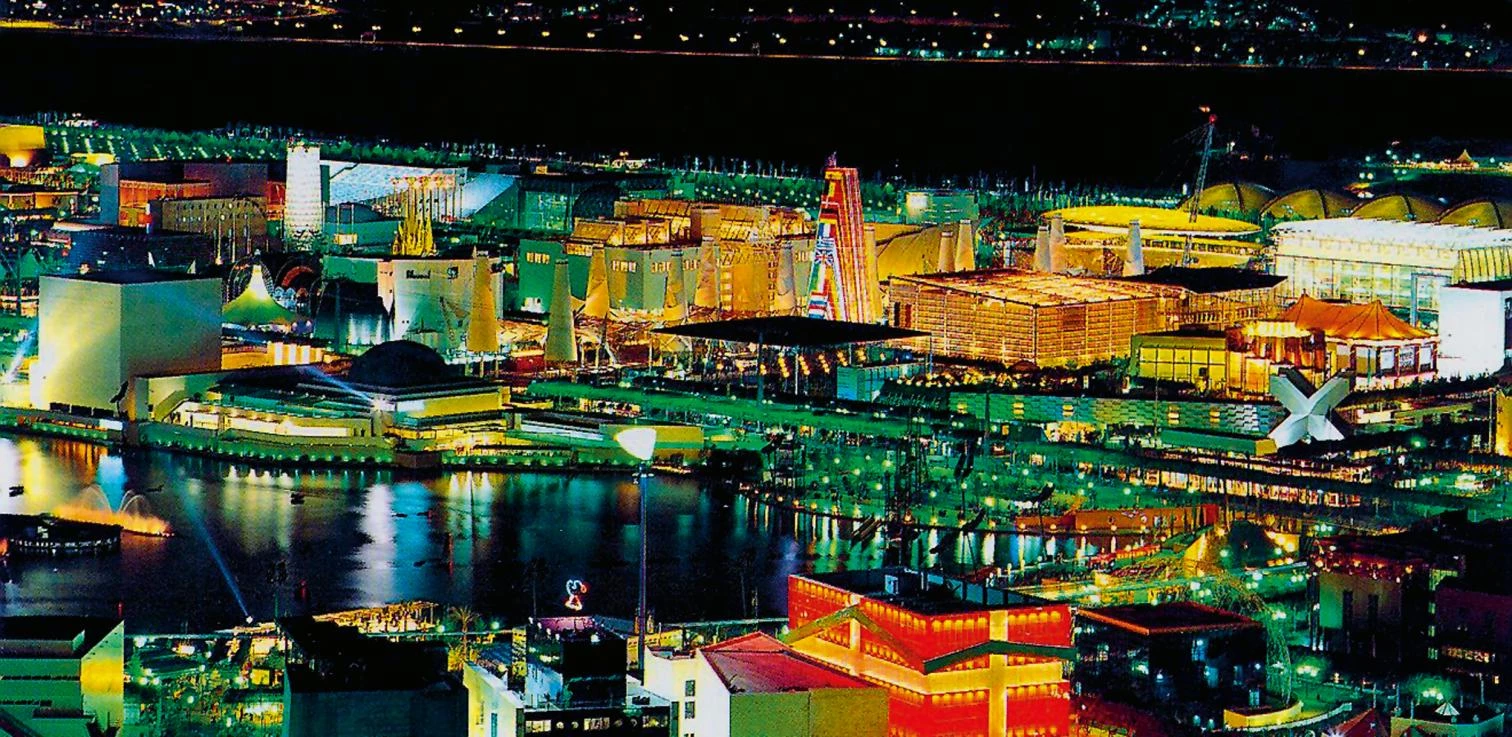

The Expo mixes silicon with silicone. The island of La Cartuja is home for six months to a magical circus that mixes the technology of image with the image of technology by blurring the line between knowledge and appearance, research and spectacle, semi-conductors and prostheses. In the wake of the Expo the island is to be turned into a technological park, but whether it will look more like a scientific park or an amusement park remains to be seen; it probably matters little, as long as the graft catches and the social fabric of Seville does not reject the transplant like a foreign body.

The rhetorical comparison between California and Florida as possible futures of the Spanish south ignores the fact that Cape Canaveral and Orlando have coexisted in Florida, as have Berkeley and Hollywood in California: Silicon Valley is not far from the Mecca of silicone. The false dichotomy between the industrial economy and the economy of services does not take into account the contemporary fusion of production and spectacle, which has turned scientists into communicators and artists into business people.

A technological project today needs a media project, and in the world of media it is impossible to survive without sound technical and organizational skills. The leisure industry brings silicon and silicone together, just like high-tech architecture needs microelectronics for climate and communication control as much as it needs joint sealants to build smooth facades: silicon, then, and silicone; physics and chemistry of the technical image.

Here, technological show is the architectural key to the fair. In the twilight of this century, power chooses to depict itself through the futuristic cosmetics of ephemeral constructions. Its baroque fiesta, which has transformed a potential vanity fair into a true bonfire of the vanities, laminates distinction to exalt difference; but beneath these deceptive differences that form the substance of representation – that’s how it is if that’s what it appears to be – technical figuration unanimously rules the modernizing approach of the fair.

Significantly, the commemoration of the discovery of America has been rid of any colonialist bone that might be too hard to gnaw. Not only the imperial adventure, but even the Hispanic dimension and Spanish language play a modest role; the ideological foes of the 5th Centenary flog a dead horse. Even Spanish unity, represented in Seville in 1929 by the bold semicircle of the Plaza de España, is hesitatingly proposed today as a fragmented arch of pavilions by the water, while some regions propose, 500 years after the conquest of Granada, to refound the state.

Technology and representation are the grooves here for the surrogate experience of the visitor, always ready for the ‘suspension of disbelief’ required in fiction, accessible only from the minority of age that opens the doors to magic, parades, and fireworks. And a formidable fiction is this corporate image campaign that amnesically tries to rebuild Spanish identity in its most characteristic city.

The magnitude of such enterprise makes architectural remarks futile. But if I had to choose an image from the Expo, I would hesitate between two works by Santiago Calatrava: the Alamillo Bridge and the Kuwaiti Pavilion. To a good part of the public and to many Sevillians, the giant harp of the bridge – which cameras magically superposed with the Giralda tower – will be a symbol of the Expo endeavor to fuse modernity with ambitions of scale and efforts in the field of infrastructures and communications.

Other visitors, surely a minority, will find in the small pavilion of the country that put the world’s TV screens on fire a year ago, the true image of contemporary culture: its two rows of sharpened fangs crowned by a light forest of palm trees that cross for a split second as they are raised, like Saddam Hussein’s arch of scimitars in Baghdad, talk at once about celebration and aggression, appearance and reality, anatomy and mechanism, biology and technique: of media silicone and futuristic silicon.

Trip to Icaria

Barcelona 92

Barcelona has got the power. As sung by Peret in the rumba that closed the games, Barcelona has shown, with the transformation of the city and the organization of the Olympic Games, its many powers. The power of talent, hard work, and money have remodeled the city’s physical texture, diffused its image all over the world, and improved the self-esteem of its inhabitants. Barcelona, Catalonia, and Spain have thrown a big party, the remains of which are a renewed city, a few debts, and many expectations.

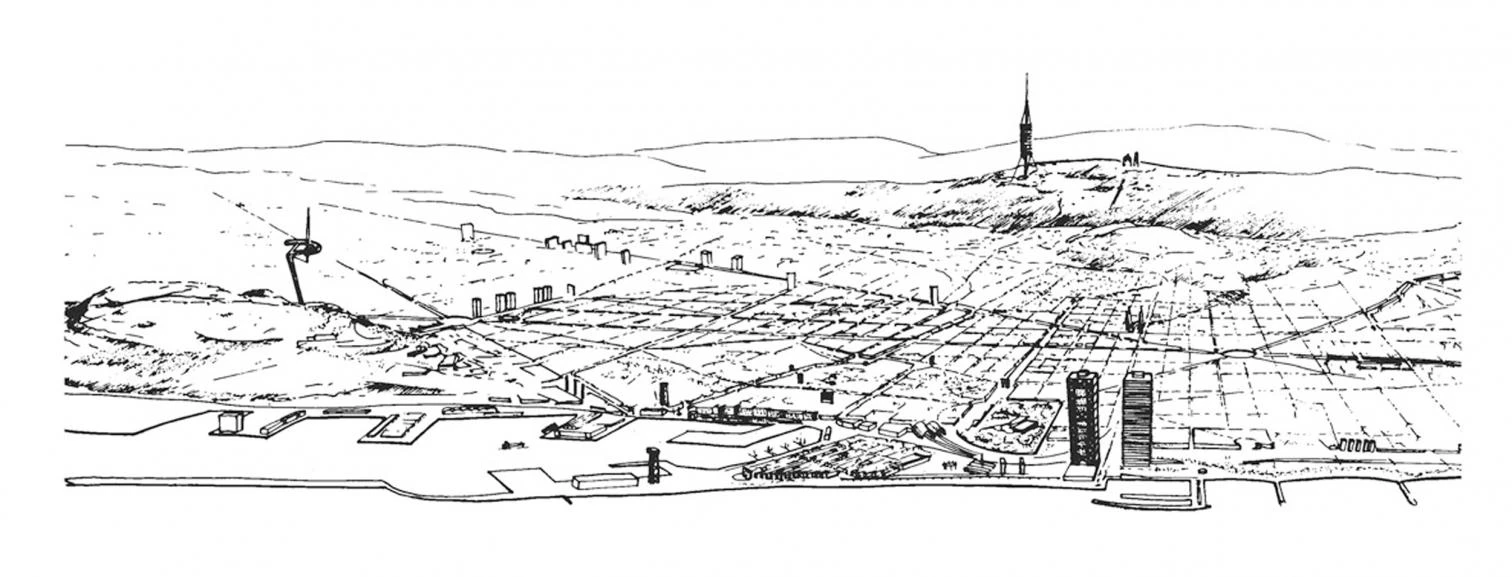

The city that has for two weeks played lady of the rings boasts a new airport, an elegant communications tower, and a circulatory road belt that links the four new Olympic areas and connects the city, now opening on to the sea through the most important of them all, the village that housed the athletes and the new recreation port.

So Barcelona has power and confidence in the future. As it wraps up the cultural buildings that were not finished in time for the Olympics – the theater, the auditorium, and the new museums – the city has decided to develop the Poblenou coastline, with an area three times that of the Olympic Village, and to stretch the Diagonal all the way to the sea. In the euphoric wake of the 10-billion-dollar Olympic success, the Catalonian capital seeks the standing in Spain and in Europe that it claims a right to by virtue of its condition as ‘north of the south.’

At this uncertain turn-of-the-century, the people of Barcelona have talentedly and tenaciously used the games as an opportunity to enhance their competitive position. The Barcelona Olympics, the first to be held since the end of the Cold War, have not set capitalism against socialism, but Nike against Reebok: they have been games of money and show, but not too different is the game played by cities, a competitive game certainly preferable to the ritual spectacle of destruction that follows a violation of rules and which, horrified and impotent, we have had to watch in Bosnia or Croatia.

The romantic Left may pine the fact that ‘the rose of fire’ of early 20th-century anarchists has given way to a rose of artificial fireworks. Yet no one can accuse Barcelona of not having assumed its role in grand style. The rhetorical question raised by Architectural Record – “Atlanta: can you top this?” – is now being answered by the introduction into society of the mascot of the southern city famous for Scarlett O’Hara, Coca-Cola, CNN, and fried chicken: Barcelonians who might have compared the indescribable Whatizit to Mariscal’s Cobi have inevitably had to indulge in chauvinism.

A good illustration of the ambiguous attitude with which Barcelona has confronted the urban challenge presented by the games is the sentimental and cynical name it has given to the real estate promotion of the Olympic Village: New Icaria. To adorn the city’s major commercial and urbanistic operation with the extravagant credentials of a French Utopian socialist who founded an ephemeral colony in Illinois, sounds as disconcerting as the determination to reconstruct the Mies and Sert pavilions or to finish Gaudí’s Sagrada Familia. In any case, the Icaria of Greek mythology provides better metaphors of Barcelona than the Icaria of Cabet.

Icarus, son of the architect Daedalus, perished upon flying too near the sun, which melted the wax of his wings: the land to which the sea dragged his corpse was named Icaria. Later the hero Icarius would live on it and receive from Dionysus, as a reward for his hospitality, the secret of wine. He in turn offered it to some shepherds, whose friends, finding them stricken by drowsiness and believing them to have been poisoned, then killed him.

To some people today Barcelona is a foolhardy Icarus, engendered by imagination and technology, sure of itself and inebriated by power, approaching the sun more than it should. To others it is a hospitable Icarius which has toasted us narcotic spectacles, facsimiles of architecture, and escapades from world conflicts. Whether Icarus or Icarius, son of Daedalus or pupil of Dionysus, neither technology nor celebration deserves as severe an ending as that assigned it by mythology. Barcelona today is a winged city with a wine glass in its hand, but it will know how to protect itself from the sun and from ignorant shepherds.