Almond with Garlands

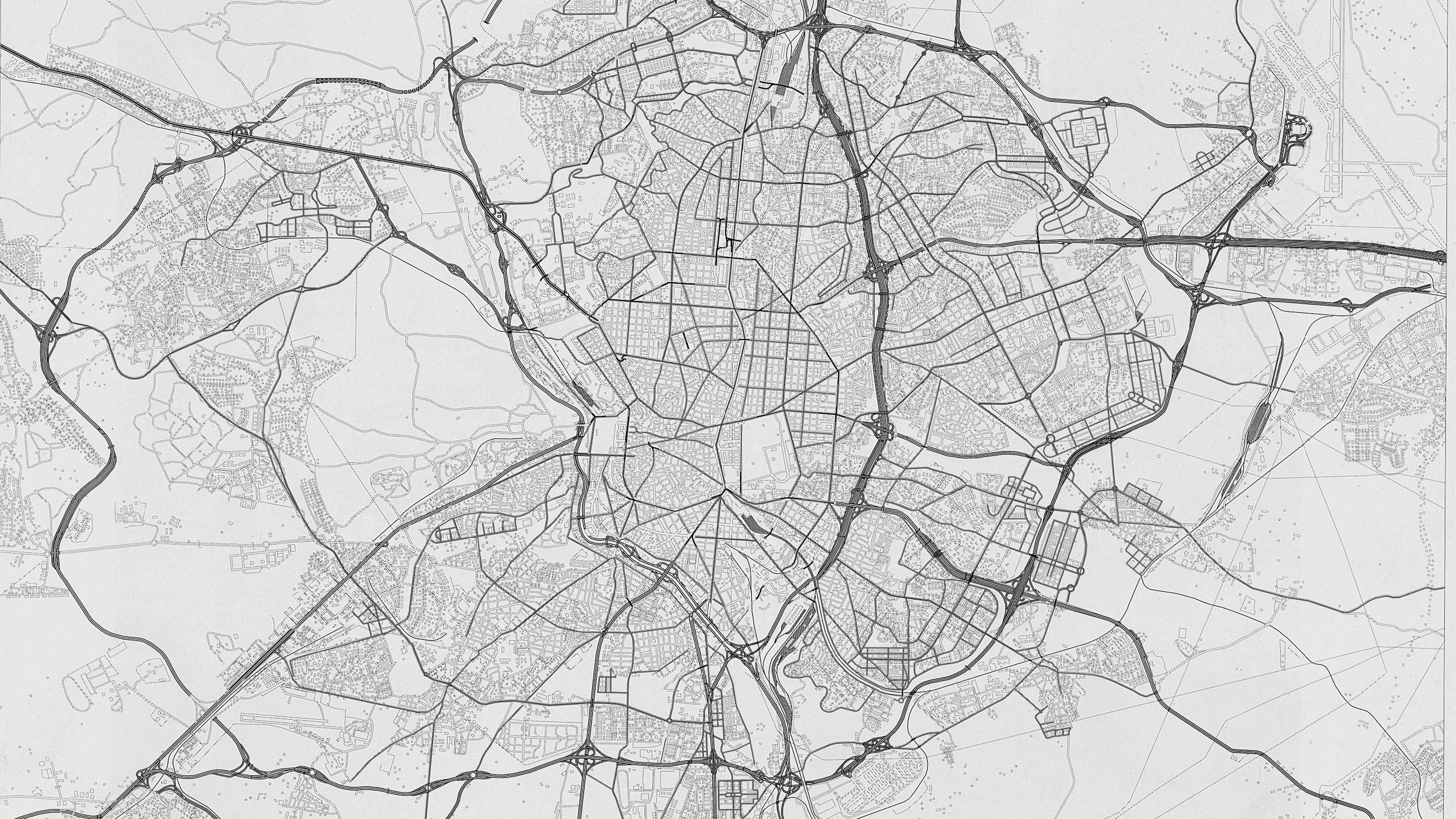

The three rings of traffic encircling Madrid accurately portray its cartography and compensate for the radial layout of its avenues.

Some images drastically alter our way of looking. The view from space that can be had of the planet transformed our very perception of the world, whose unitary and delicate nature was from then on clearly fixed in our minds and retinas. Similarly, the methods of representing architecture, the city and the territory throw as much light on the objects being represented as they do on the authors of the images. Between Renaissance perspective and computer graphics, or between medieval cartography and the contemporary aerial shot, lies not only a technical and scientific abyss, but also a symbolic one that gapes between gazes and intentions. Every epoch looks and records in a different manner; and every epoch sees differently.

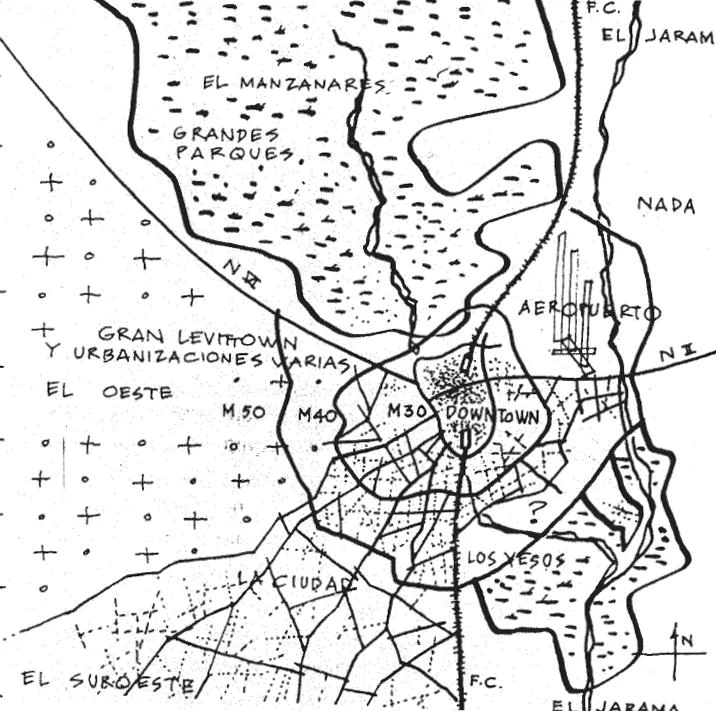

Madrid has been seen in many ways, but a recent one strikes me as especially significant: this is a map in which the belt of highways figures as the most important feature, and which in several versions has appeared in the press in past years, usually in the context of the completion of the M-30, the closing of the M-40, or the drawing up of the M-50 - the city’s three successive rings. For those used to thinking of Madrid as kilometer zero in a web of radial roads (with a knot at the Puerta del Sol that the metro network served to reinforce), such a picture of what urban planners called the ‘central almond’, surrounded by the dizzying snarl of the M-30 and the tentative wiring of subsequent peripheral halos, must have traumatic perceptive consequences: this mystical almond provokes either panic or conversion.

A map of the capital allows one to read its layout as an almond laced by the M-30 ring road and a second ‘garland,’ built only in part, that connects the urban nuclei which have emerged along incoming routes.

From its automobile Pantocrator, where the almond’s shell has given way to the frantic tangle of traffic, the new Madrid strikes a sharp contrast with the capital’s more persuasive image of the seventies: the multicolor scheme of subway lines, in whose exact geometric abstraction flowed the even pulse of the city. The everyday systole and diastole were regulated by the underground solar heart of interchanges, and the population circulated within an at once noisy and mute network of electrical ganglions. Not even the construction of the bridges and tunnels of peripheral boulevards could alter the general perception of Madrid as a radial place. But the M-30, which was finally closed on the north by three timid parallel strands, would change it all.

Our Madrid, which began its democratic career with the romantic gesture of eliminating the Atocha overpass, has entered the nineties with several garlands of highways hanging from its cartographic neck, in the amiably carefree manner of Pacific tribe chiefs or Formula 1 racers. Between the asphalt roses of the ribbons and the coiled laurel of the knots still beats a cordial, almond-shaped center, split by the vertebrated river bed that is the Paseo de la Castellana. In the years of weak economy, it sufficed to cure Madrid through urban acupuncture; during the prosperous second half of the eighties, the city has been put through general surgery with extracorporeal circulation. Thus, in just a decade, the city has passed from alternative medicine to advanced hospital therapy. The urbanism of repair and continuity has given way to the urbanism of highways and outskirts.

The symbolic and polemic force of the garland decked almond pales the architectural images of past years. Some certainly deserve mention, and the most significant of these are located at the two far ends of the split between cotyledons, that torrent of traffic that pierces Madrid from north to south, and which has more right to be the city’s river than the anonymous Manzanares: to the north, the latest upgrowth of office skyscrapers; to the south, the rehabilitation of old buildings to accommodate new museums. It is between these emblematic poles of money and culture - the leisure south and the business north - that the life of Madrid still pulsates.

Up north along the Castellana, the Picasso Tower rose in the second half of the eighties as a faithful representation of the opulence and economic optimism of those years. Designed some time back by an architect who died not long after, Minoru Yamasaki, its perfect banality and its adequate location in a paradigmatic non-place (the Azca zone) made this building, incidentally the peninsula’s tallest, a coveted set-up for companies whose business it is to represent. It unnotoriously inscribed itself in the city’s skyline, and only the spectacular night lights, enhancing the crown that Gerardo Alas had added to the project, could prevent it from becoming outright trivial. The tower’s clumsy daytime bulk transforms phantasmagorically at nightfall, rising like a slender shaft whose blinding whiteness describes the pale and exact firmaments of money.

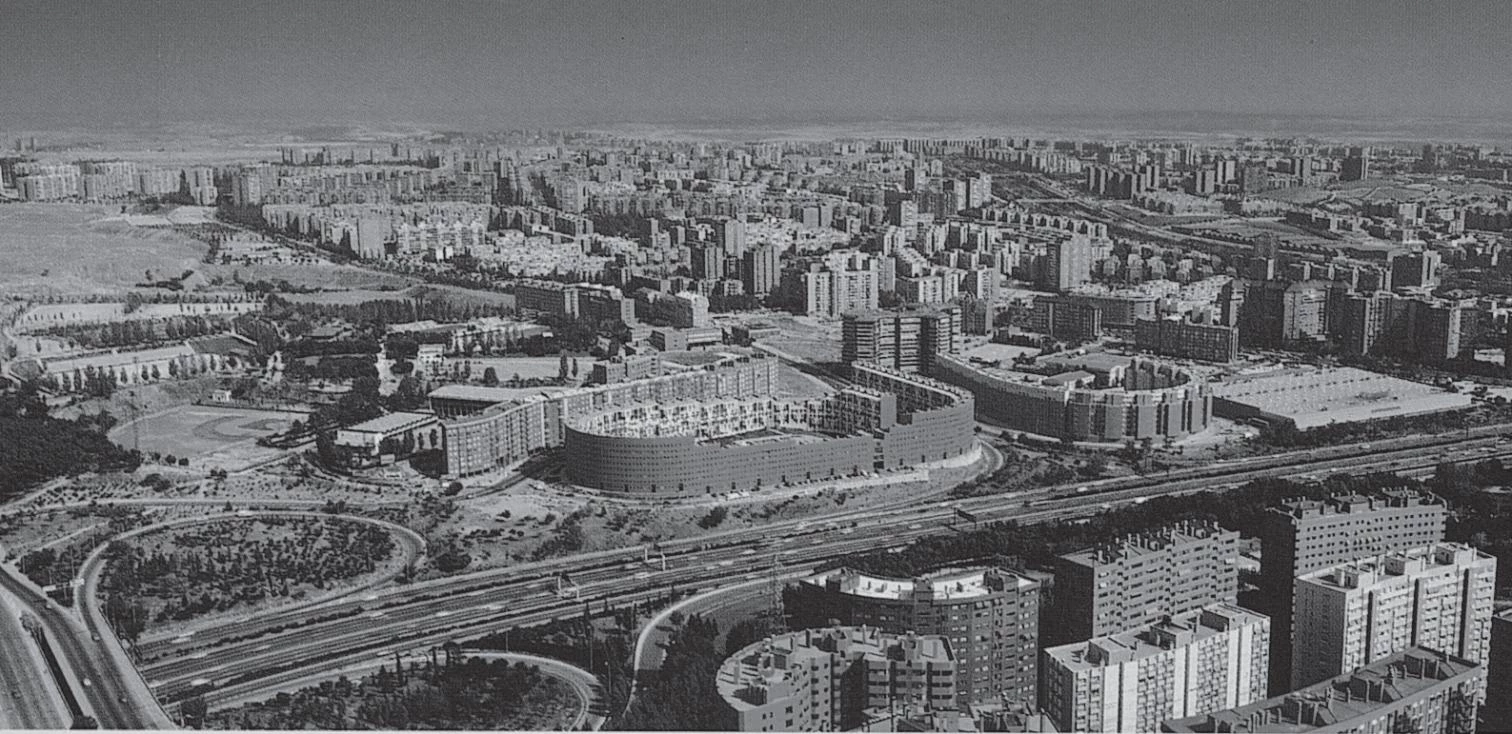

Linking corporate headquarters in the north (above) to Atocha Station in the south, the Castellana avenue splits the city in two. Among the residential projects that sprang up along the M-30 in the eighties, the dwellings of Sáenz de Oíza stand out (below). Now that this route has been fully developed, the M-40 belt has been declared as the new display window for a Madrid which has yet to be built.

If the Picasso Tower represented the prosperity of the eighties, the leaning KIO towers on Plaza de Castilla perfectly reflect the economic and political crises of the decade’s end. Designed by the American firm Johnson & Burgee for the Kuwait Investment Office, which has considerable interests in Spain, everything about them seems to be in crisis. In crisis is the investing country, which has still to recover from the invasion, the war and generalized destruction, and where democratizing hopes and promises formulated on the occasion of the western intervention have only met with frustration. In crisis are its interests in Spain, all jumbled up in an impossible maze. In crisis is Spain itself, a nation plunged into a period of economic adjustment, pulled away from Europe’s leader group, and increasingly demoralized by its politicians. In crisis is the real estate sector, all paralyzed by uncertainty and having witnessed the collapse of giants like Olympia and York. In crisis, finally, are the architects themselves, who in the wake of a bitter separation pecked with any number of lawsuits have declared their studio bankrupt.

These inclined towers, pompously named the Gateway to Europe, wonderfully illustrate the instability of European dreams and the precariousness of recent opulence. But badly regarded as they are on both sides of the Atlantic, with Madrileños and New Yorkers alike denouncing their vulgar build and urban insensibility, the fact is that they have inserted themselves into the city’s distant profile with resounding eloquence. Despite the lamentable crudeness of the gesture, it is hard to deny that they already form part of Madrid’s characteristic silhouette. In addition, their rhetorical slant captures both the fantasies of an Olympic Spain and its awakening from the dream.

On the southern end of the Castellana axis, a hospital and a palace turned into museums reveal at once the limitations and aspirations of Spanish and Madrid culture. The Reina Sofía, an old hospital converted into a museum by Antonio Fernández Alba, José Luis Íñiguez and Antonio Vázquez de Castro, inaugurated its permanent collection just a month after the opening of the Thyssen Collection, which has a ten-year lease in Villahermosa Palace, as remodeled by Rafael Moneo. Situated in the vicinity of the Prado, the Reina Sofía and the Thyssen join with it to form a magical triangle of the arts. In contrast to the overwhelming dimension and richness of the Prado’s holdings, however, the Reina Sofía and Thyssen boil down to two projects: a collection project and a permanence project. The former painfully brings to light certain lacunae in our visual culture of the past century; the latter ostentatiously expresses the stubborn determination to fill them up, however ludicrous the cost. It might be in such cyclothymic arrhythmia that the city’s ignorant and courtesan nature rests.

The Reina Sofía hides its patrimonial and programmatic miseries behind a pair of glass elevators designed by Britain’s Ian Ritchie that make it a caricature of the Pompidou Center, while the Thyssen Museum nestles its inured ecumenical possessions in a soberly exquisite, palatial candy box that constantly brings to mind the economic dimension of the works and the financial engineering behind the operation. In both cases, one’s esthetic pleasure or pain is accompanied by the venial tremor of greed or amazement: art presents itself as the ultimate luxury of decadents and moderns, who swim around like impeccable sharks amongst tempered windows and peach-colored walls.

If the Picasso and KIO towers form part of Madrid’s physical profile, the Reina Sofía and Thyssen museums grace its symbolic profile with equal aplomb, situated as they are around the magnetic stone of the Prado, imaginary core and heart of the city’s almond. All other operations dim in its categorical presence. Some are more visible, or perhaps more critical to the competitive future of the metropolis, but nothing represents its essential ambiguity as efficiently as these towers of the north and museums of the south.

The large-scale operations in the transport field, namely the huge hypostyle Atocha Station and the interminable acres of the new fair premises, close to a Barajas Airport in dire need of enlargement, have a physical size that far exceeds their symbolic scale. The new sport arenas, such as the beautiful, impassive peineta of the track-and-field stadium or the megastructure of the remodeling of Real Madrid Stadium , lack both the central location and programmatic novelty thatwould otherwise ingrain them onto the awareness of citizens. The ironic,Venturian classicism of the new Congress building and the contained, pragmatic postmodernism of the new Senate construction are obscure works in comparison, on one hand being mere extensions, and on the other, due to the presently low profile of the institutions they house. Finally, the latest additions to the canonical silhouette of the city’s west cornice, including the dispensable lighthouse of the Moncloa Observation Tower and the historicist dome of the obdurate Almudena cathedral, simply lack the esthetic refinement that the dignity of the surroundings demands.

Significantly, the only building of the past years to have aroused impassioned controversy is the ‘bullring’ on the M-30, a housing complex designed by Saénz de Oíza whose domestic nature should have shielded it from public attention, but whose location on the circular highway route has put it in the hub of general interest. The fact is that this speedy and populous belt is now our plaza mayor. And in this busy garland of the almond, we have learned a new way of looking at things. When we have a bird’s eye view of it or see it transcribed on new maps, we can hardly avoid the vertiginous and lasting conviction that this murmuring tangle of routes is the most genuine vista of Madrid.