Troubled times

Natural catastrophes and social convulsions have provided the backdrop to an architectural year marked by the loss of a large number of masters.

This has been a year of natural catastrophes and social cataclysms. From the echoes of the tsunami of the Indian Ocean to the Kashmir earthquake or the Caribbean hurricane which devastated New Orleans, the violence of the elements made us discuss climate change. In Spain, the fire that destroyed the Windsor building in Madrid and the collapse of the Carmelo neighborhood in Barcelona stressed the fragility of our cities. In the social and political field, the never-ending tragedy of the near East (with the bloody conflict of Iraq, the instability of Iran or Lebanon, and the uncertainty of both Israel and Palestine without Sharon or Arafat) resonates with the anarchy of the American superpower, embarked on an aimless journey of military aggression and clandestine prisons, and the impotence of a Europe that, after rejecting its Constitution and entering a leadership crisis that only seems to have spared the newly arrived Merkel, has been shaken by Islamic terrorism in London, the wrath of the youth in the decaying urban peripheries of France and the desperation of the illegal immigrants in the Spanish cities of northern Africa.

Natural catastrophes and social convulsions have provided the backdrop to an architectural year marked by the loss of a large number of masters.

Apart from that, architecture followed its own path, increasingly spectacular and self-absorbed, using the great exhibition and sports events as fuel for urban renovation. Hence the importance of the vie to host the 2012 Olympic Games, that Madrid – under transformation with the ‘big dig’ of its ringroad – did not win, falling behind the victorious London and a stubborn Paris, but before two imperial metropolis, the martyr New York of 9-11 and the Moscow of Putin; all of this while Valencia prepares the America’s Cup of 2007 and Zaragoza the Expo of 2008, which have sparked numerous competitions and projects. In the world, the year witnessed the celebration of the Universal Exposition of Aichi, where the London-based architects Zaera & Moussavi built a fine Spanish pavilion with ceramic hexagons, and the triennial congress of the UIA, which awarded its medal to the Japanese Tadao Ando in a ceremony held in Istanbul.

The Windsor building fire and the destruction of New Orleans by Katrina showed the fragility of our cities.

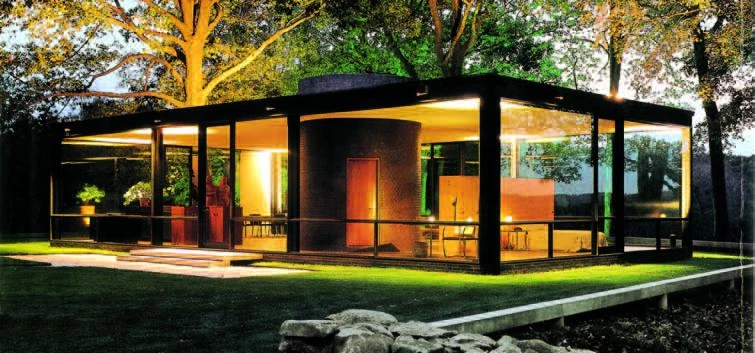

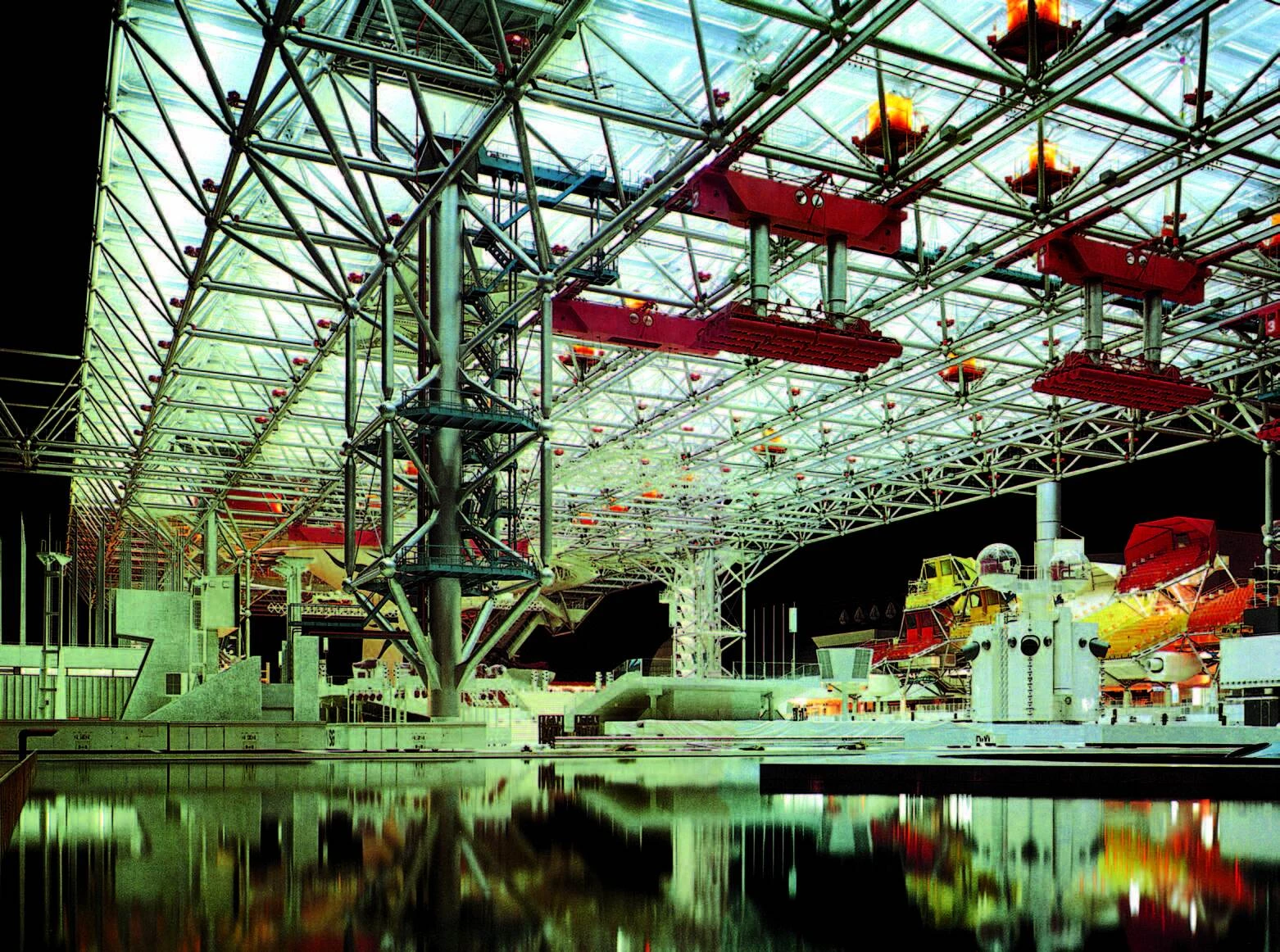

In a year marked by the live broadcast of the death of the Pope John Paul II, architecture had to mourn the disappearance of many masters, though almost all of them had stepped off the stage a long time ago: Philip Johnson, the great arbiter of the New York scene; Ralph Erskine, the British-Scandinavian pioneer of ecology and participation; Kenzo Tange, who used technique to build the symbols of post-war Japan; Giancarlo de Carlo, the engagé humanist Italian who was the last survivor of Team X; Fernando Távora, master of Siza and founder of Portuguese modernity; James Ingo Freed, the partner of I.M. Pei who designed the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington; or Constant, the Dutch sculptor author of the New Babylon. Besides the Spaniards, from Francisco de Asís Cabrero, author of the Trade Union building, who built fascist and rational architecture, to the Sevillian Manuel Trillo, the Alicante architect Juan Guardiola or Madrid’s Javier Feduchi, member of a distinguished saga of architects and furniture designers.

The American Philip Johnson (right, the Glass House of 1949) and the Japanese Kenzo Tange (below, the megastructure of the Expo’70 in Osaka, his metabolist testament) were two of the figures dissapeared in the year.

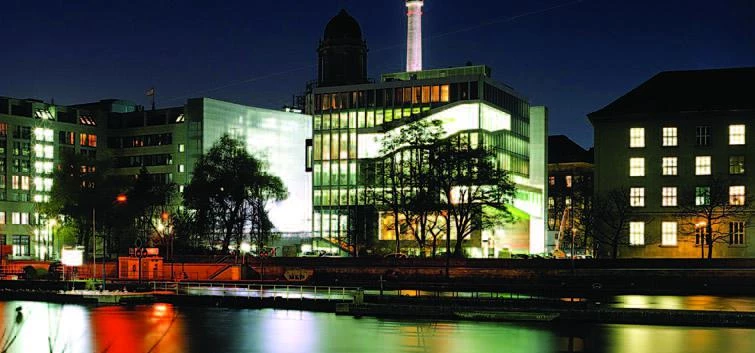

The European Mies award went to Rem Koolhaas for the Dutch Embassy in Berlin (left), while the Pritzker Prize winner was the California architect Thom Mayne (below, his Caltrans headquarters in downtown Los Angeles).

The same can be said of the drizzle of prizes, which celebrated careers or noteworthy buildings without opening different paths to that of the exaltation of the author and the oeuvre. So, the Pritzker went to an enragé, sexagenarian California architect, Thom Mayne, and the Japanese Imperiale was rightly bestowed on the author of the MoMA remodeling, Yoshio Taniguchi; both the British and the American gold medals distinguished architecture with an engineering flavor, the first going to Frei Otto and the second to Santiago Calatrava; Rem Koolhaas won the Mies award for the Dutch Embassy in Berlin, and the late Enric Miralles received, for the Scottish Parliament – completed by his widow Benedetta Tagliabue –, both the British Stirling Prize and that of the Spanish Biennial; lastly, the National Award of Spain went to Guillermo Vázquez Consuegra for the redesign of Vigo’s seafront, while the FAD, an award that now covers the whole peninsula, to Eduardo Souto de Moura for the muscular concrete shapes of Braga’s stadium.

The Spanish pavilion in Aichi (right), by FOA, was as media-savvy as the Agbar tower by Nouvel in Barcelona or the City of the Arts and Sciences by Calatrava in Valencia, which was rounded off with a grand auditorium.

The Art Review published its annual list of the one hundred most influential people in the art world, and on this occasion the list included four architecture firms: the Swiss Herzog & de Meuron, who after inaugurating the pneumatic Allianz Arena in Munich have opened two museums in the United States, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and the New De Young Museum in San Francisco; the Genoan Renzo Piano who, aside from completing the Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern, has finished the extension of Atlanta’s High Museum of Art; the aforementioned Koolhaas, who has opened a Prada Store in Los Angeles and a colossal Casa da Música in Porto; and the Anglo-Iraqi Zaha Hadid, who has completed works in Wolfsburg and Leipzig. Much praised buildings that join the Holocaust memorial by Peter Eisenman in Berlin, the pavilion by Frank Gehry in Chicago’s Millennium Park, the Fira of Milan by Massimiliano Fuksas, and the works by Jean Nouvel in Madrid and Barcelona, to compose a still life of excellence or fatigue that also includes some significant completions in the peninsula or the islands, from the Palace of the Arts by Calatrava in Valencia to the Congress Center by AMP in Tenerife. The chapter of anniversaries and events was reiterative and duly foreseeable. The year of Einstein was also that of the four hundred years of the Quixote, spurring a fuss of hyperbolic celebrations, with no other architectural fruits than a tribute to La Mancha’s most universal architect, Miguel Fisac; the centennials of Albert Speer and Juan O’Gorman, two architects of extraordinary and antithetical political dimension, went more unnoticed than that of Las Vegas, which is quite revealing about the ideological temperature of the times; and also meaningful is the scarce commemorative effort sparked by the 50th anniversary of Hiroshima, a historic abyss that shuns compassion and forgiveness. It has been a year of memory and amnesia, drowsy and convulse, tragic as much for the calamities experienced as for the sensation of loss of direction in the governance of this vulnerable planet.