The Coming Gale

Democracy’s fatigue and general indignation with social and cultural elites prefigure a period of political storms and economic mutations.

Europe has observed the anniversaries of the beginning and end of a short century with mixed feelings. The centenary of the Great War has given rise to commemorative monuments, promises of atonement, and historical studies which pinpoint responsibility for the catastrophe on sleepwalking elites perhaps no different from today’s; for his part, the twenty-five years since the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War have been remembered with good intentions and retrospective satisfaction, enhanced by the thawing of tensions between Cuba and the United States, although a pall is cast over them by the unequal distribution of the dividends of peace and the proliferation of conflicts in the Russian glacis, most dangerously in Ukraine.

All this in a geopolitical context where migrations continue to threaten the fortresses of prosperous countries; where popular protests have arrived at the threshold of the planet’s most populated country; where energy again plays a dominant role, with the drop in oil prices doing as much harm to authoritarian populist regimes – from Russia to Venezuela – as to renewables and fracking, while Asia asserts itself with strong leaders like Xi Jinping, Narendra Modi, or Shinzo Abe; Africa reveals its structural weaknesses with the ebola crisis; the Middle East bleeds with the persistent war of Syria and the cruel rise of the Islamic State; and the Americas concentrate on their own problems, paying less attention to connections and interests shared with the Old World.

The Venice Biennale, the Mexico City airport, and the Rotterdam Markthal were the show, project, and work of a year that in London remembered the centenary of the outbreak of the Great War with a sea of ceramic poppies.

In Spain, lukewarm economic recovery has done little to alleviate the climate of malaise created by lingering unemployment and proliferating scandals, which have brought citizens’ confidence in institutions down to a minimum while bringing about the dazzling rise of a new political movement – Podemos (We Can) – which puts into question the two-party regime that arose from the Transition and promises some electoral quakes in the near future. Not even the generational changing of guard in the house of the Head of State – with King Juan Carlos I abdicating in favor of his son, now Felipe VI –, in the socialist party – with Pedro Sánchez replacing Alfredo Rubalcaba –, and in the leadership of several large banks and companies has significantly lessened the divorce between public opinion and a bloc of political and economic elites holding on tight to their privileges, painting a picture of uncertainty that the tenacious secessionist tensions of Catalonia only increases. For architects, the return of confidence and growth has meant a certain promise in the field of real estate, as well as the confirmation of the arrival of international investment in the sector; but the virtual inexistence of public promotions is still forcing many of the best to look for work abroad.

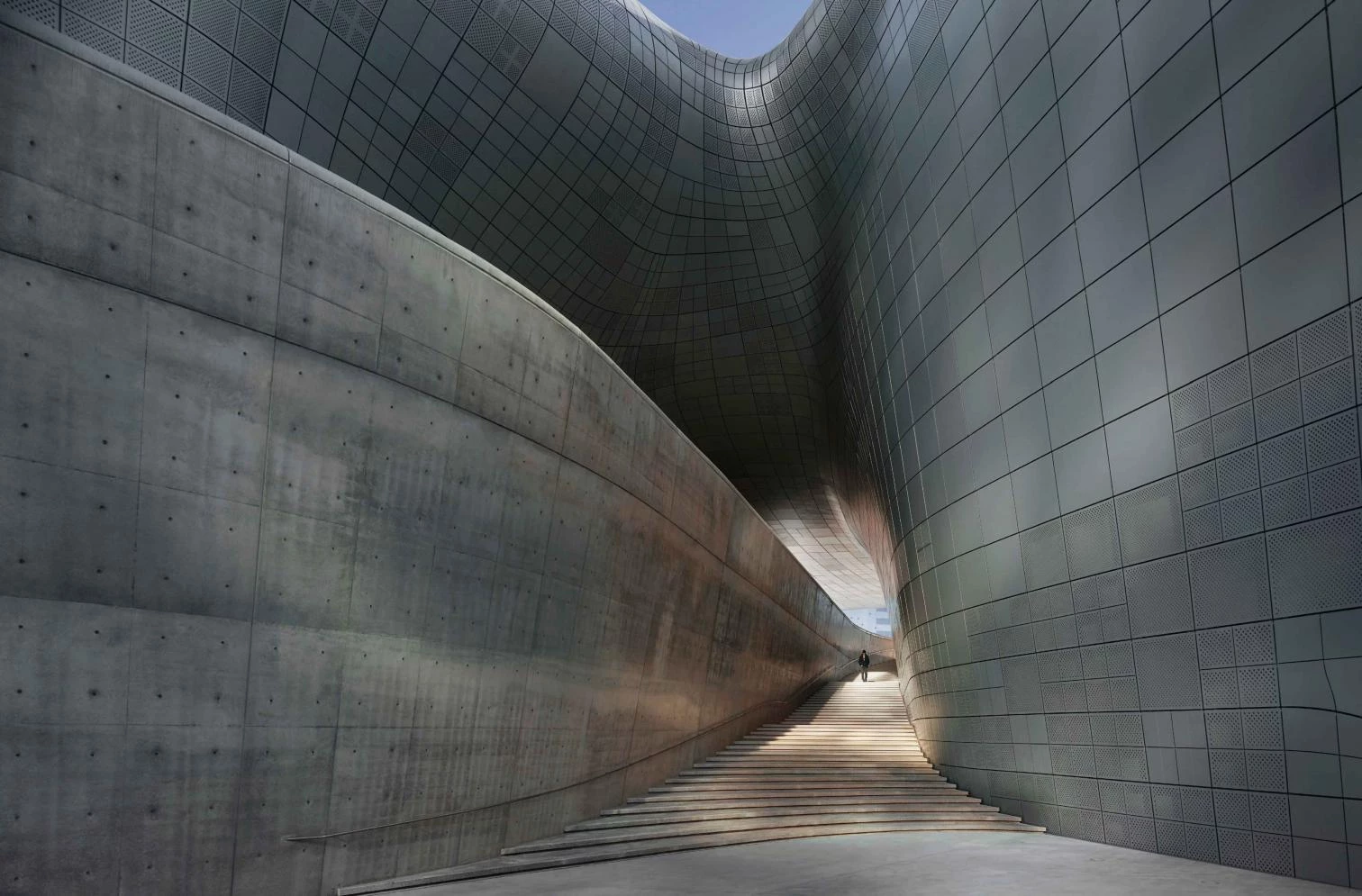

The year of the Rosetta probe in science and the fourth centennial of El Greco in culture had Rem Koolhaas as its architectural main character. With a large exhibition on the Elements of Architecture, the Venice Biennale curated by the Dutch drew attention to the fundamentals of the discipline, challenging the protagonism of architects and architectural language in the past decades, and perhaps expressing a certain weariness with icons. The exhibition coincided in time with a speech of China’s president censuring ‘weird’ architecture – ironically using the CCTV of Koolhaas, no less, as example – and both the exhibition and the speech reflect the change in the aesthetic climate, something also evident in ‘The Architect is Present,’ a show-plus-workshops where Francis Kére, TYIN, Solano Benítez, Anupama Kundoo, and Anna Heringer presented new paths to young people, and in ‘Necessary Architecture,’ a congress organized by the Fundación Arquitectura y Sociedad and held in Pamplona, where Álvaro Siza explained the extent to which we also need beauty. But the mutation of the critical mood has significantly affected architects possessing an artistic dimension, and so it is that Zaha Hadid has suffered heavy criticism for her works for Soho in China, her cultural complex in Seoul, or her successive projects for the stadium of the Tokyo Olympics, and the same can be said about Steven Holl and his extension of Mackintosh’s Glasgow School of Art (the library of which would, to boot, be razed by fire later in the year), or about Frank Gehry and his last two openings, the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris and the BioMuseum in Panama, despite the aesthetic merits of both.

Criticized by many,

the year’s iconic works include two by Gehry, the Biomuseum in Panama and the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris, and two by Zaha Hadid, the Wangjing Soho in Beijing and the DDP in Seoul.

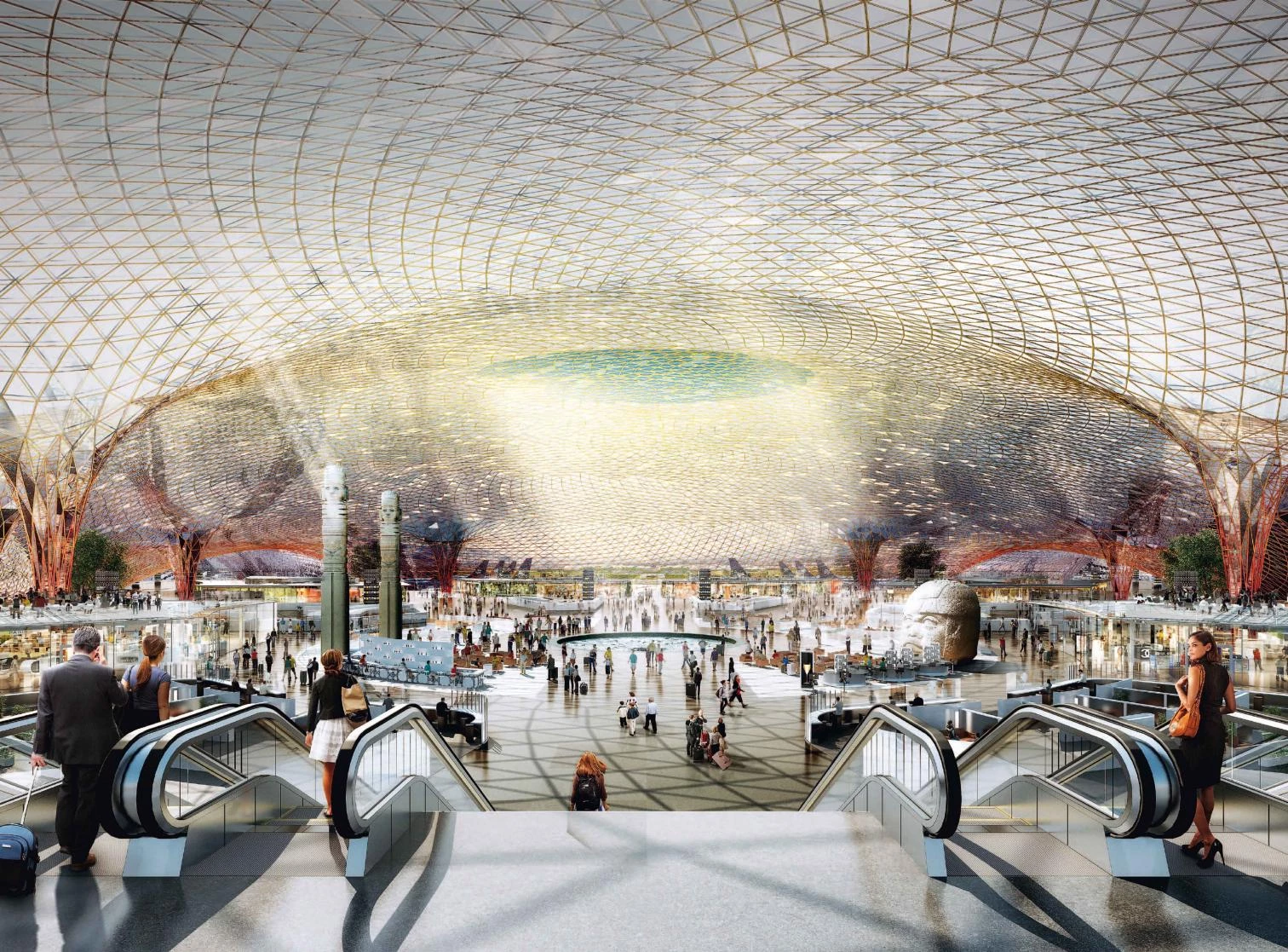

The year has been kínder on Norman Foster, who gave up the prospect of establishing his Foundation in Madrid, but won the competition to build Mexico City’s new airport with a visionary design that picks up on his early collaborations with Buckminster Fuller; on Renzo Piano, who opened the biomorphic Pathé Foundation in Paris and the exemplary renovation of the Harvard Art Museums in Cambridge; on Herzog & de Meuron, who completed his fourth building for Ricola, an exquisite shed raised with large panels of rammed earth, and a gymnasium under a colossal roof on the edge of a Brazilian favela; or on MVRDV, whose Markthal in Rotterdam mixes marketplace, dwellings, and public square with pop sensibility and figurative daring. And despite the difficulties in Spain, some Spanish practices completed major works on the Peninsula: Nieto Sobejano the Barceló Market in Madrid, Francisco Mangado the Fine Arts Museum in Oviedo, Carme Pinós the CaixaForum in Zaragoza, Rafael Moneo a tower in Barcelona, and the team formed by Pancorbo, De Villar, Chacón, and Martín Robles a topographical Congress Center in Villanueva de la Serena. In contrast, Barrozzi Veiga opened their most important work so far in Poland, the philharmonic hall of Szczecin, as did RCR in the south of France, with the ascetic and lyrical Musée Soulages.

In the awards chapter, the Pritzker went to Shigeru Ban, the Imperiale to Steven Holl, the Prince of Asturias to Frank Gehry, the Swiss BSI to the Spaniard José María Sánchez, and the Basque BIA (in its first edition) to Norman Foster. Besides, Phyllis Lambert received the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale, I.M. Pei the UIA Gold Medal, Joseph Rykwert the RIBA’s, the mythical Julia Morgan the AIA’s, the Andalusians Cruz & Ortiz the Spanish Gold, and the Santander-born Juan Navarro Baldeweg – who also inaugurated an anthological show in Madrid – the National Architecture Award; while the Stirling and the FAD were given to the Everyman Theater in Liverpool, by Haworth Tomkins, and the pedestrian route in Lisbon, by João Pedro Falcão.

Finally, the year of the centennials of José Luis Fernández del Amo, Denys Lasdun, Ralph Erskine and Lina Bo Bardi also bid farewell to the British Kathryn Findlay, the Austrian Hans Hollein, the Brazilian Lelé, the Cuban Ricardo Porro, the Portuguese João Á. Rocha and the French Michel Corajoud, and to planners Peter Hall and Bernardo Secchi, or David Mackay and Tony Díaz, a Brit and an Argentinian based in Spain; and the list also includes the master Rafael Aburto and the architect-teachers Manuel de las Casas and Albert Viaplana, who left works and disciples in Castile and Catalonia.

Spain saw the opening of the CaixaForum by Pinós in Zaragoza and the museum by Mangado in Oviedo, and France and Poland, the Musée Soulages by RCR in Rodez and the concert hall by Barozzi Veiga in Szczecin.