I have no doubt that two substantial vectors of the evolution of 21st-century architecture are sensuality and sustainability. Sustainability is unavoidable for obvious reasons, but architecture is also in debt to comfort. Sensuality, the pleasure of the senses, fell into oblivion when the Modern Movement, obsessed with geometric minimalism, held it in contempt. Eileen Green expressed it well: “As if a house should be conceived more to please the eye than to address the well-being of the inhabitants.”

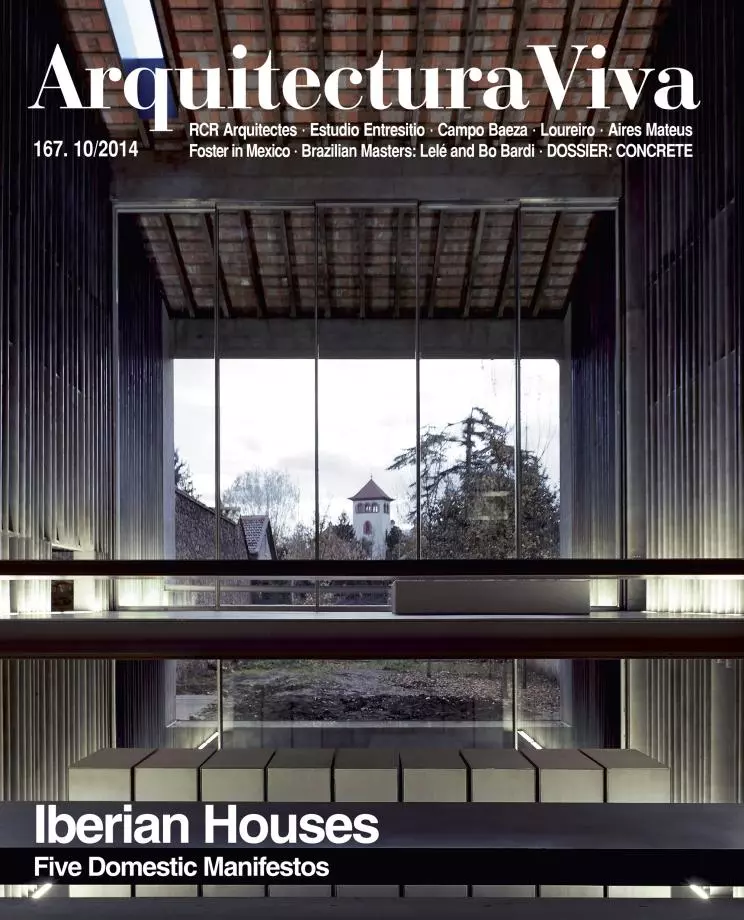

The answer to these demands can be given by filters. On the website ‘filt3rs,’ it is clear that all the facades analyzed are protected by elements through which comfort and energy flows can be controlled. Does this mean that the facade of sustainability and comfort will be one of blinds, awnings, and shutters? In theory these elements suggest a picturesqueness that is rejected by minimalist outlooks, and many architects and clients will continue to ask for the terse glazed skin of office buildings.

Let us now talk about sustainability, in particular solar protection. Is there a solution that could preserve the glazed look while solving the problems of excessive sunning? We can resort to physics: if the material used for indoor protection is reflecting, whether white or silvery, the reflected radiation penetrates the glass again and escapes to the exterior. This is the reason for the white color of traditional lace curtains and hangings. The reflection of much of the energy is valuable, but it is insufficient if heat continues to be produced inside, as happens in office buildings. But if we were to place these reflecting elements in an air chamber and we extract through the air inside, we could solve the problem. Unfortunately the volume of air to be moved is excessive, so it would not be worth the effort. Nevertheless, with the air that must be extracted if we are to comply with ventilation regulations, it is possible to form a lamina that maintains the inner glass at the temperature of the interior space.

Again, physics can come to our aid. In the dynamics of fluids, there is a little known effect that could be expressed in this way: a lamina of a fluid in motion whose stream near a surface tends to attach itself to that surface and remain unaffected, in such a way that the interior air moves through the chamber licking the inner glass and without mixing with the rest of the air, very hot air, of said chamber.

We cannot here take stock of these phenomena in all their complexity, but I do wish to draw attention to how little is left of our physical intuitions. Accustomed as we are to moving with the imagery of mechanics, we are clumsy when it comes to the dynamics of fluids, let alone that of the chemical.

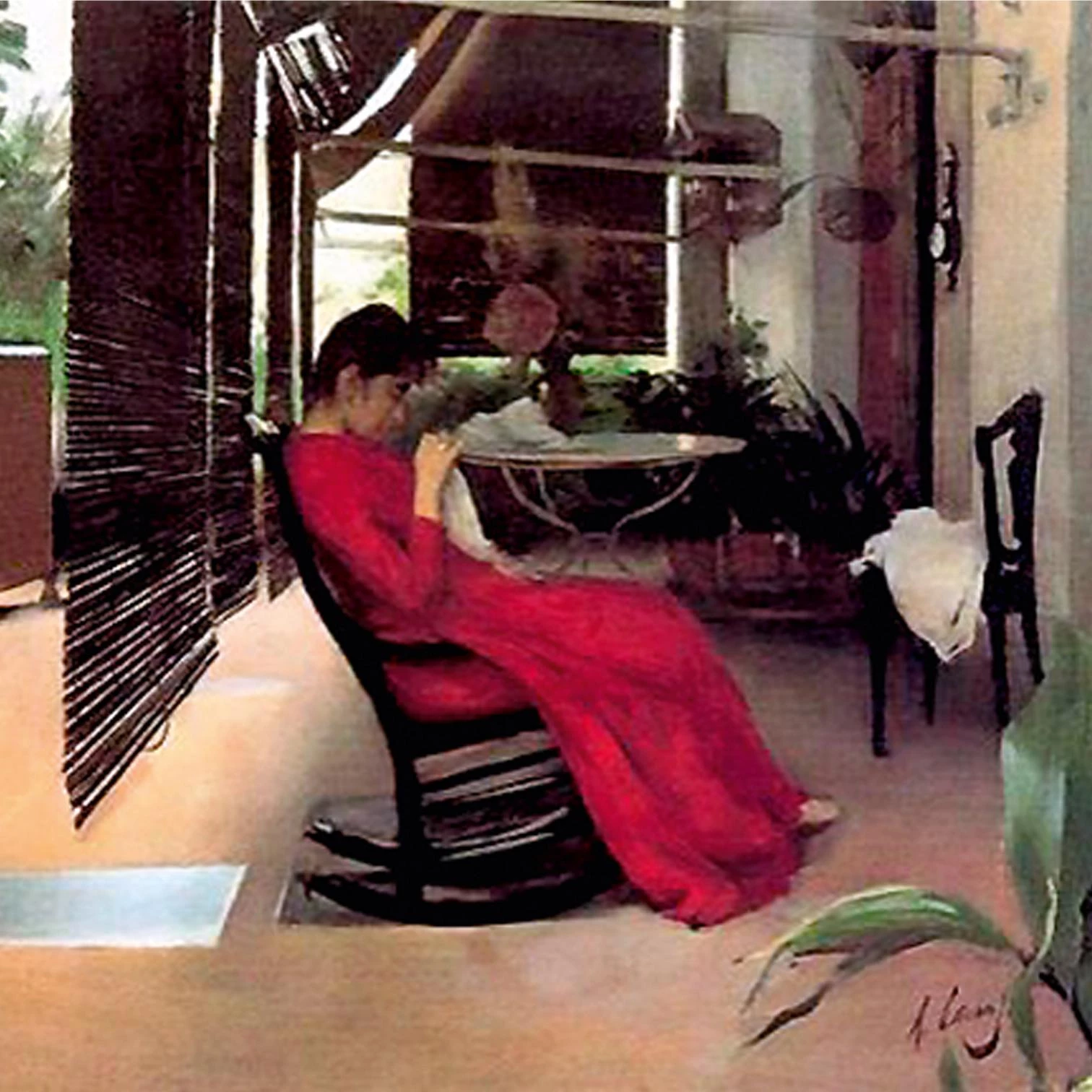

Let us return to sensuality and think of the ascetic, arid, and unprotected spaces of our residential architecture. Let us turn to the treatment of light, the character of windows. The beautiful composition of the frames in the Maison La Roche conceals a disdain for comfort that is evident in the divan of Le Corbusier which looks impossible to lie down on. James Turrell explains why: “We are not made for so much light, but for the light of twilight. Our pupils only dilate when very low intensities of light are reached. When they at last dilate, we begin to really feel the light, almost like touching it.”

I wish to encourage my colleagues to make sustainable buildings and sensual interiors. Interiors drawn with the right penumbra, swept by gentle breezes, and acoustically cushioned. Interiors where we can open a window to intimacy.