“The problems of long-lasting sexual relationships are aggravated by economic dependence and are really imposible to solve.” With this statement Wilhelm Reich – psychotherapist and inventor of one of the craziest sex machines of the 20th century, the orgone – began the chapter ‘The Problem of Marriage’ in the book The Sexual Revolution, translated to English in 1949, and his veiled allusions to the ambivalences of marriage seem clear. To address unsolvable frustrations, Reich proposed a therapeutic technique in which liberation of desire in the patient would take on a basic role through the attitude of the professional, and through the abovementioned orgone, a kind of pleasure cabin which, according to its autor, releases a liberating sexual energy.

A few years after the publication of this text, when these outlandish and very fleeting techniques were in full swing, another eccentric masculinized inhabitable spaces and filled them with desire. Or he turned them into pure lust by governing the world from the round bed in his mansion. From there Hugh Hefner established his Playboy empire, which, though hard to believe, was born in the 1950s – a time full of role impositions – as a cry for masculine freedom.

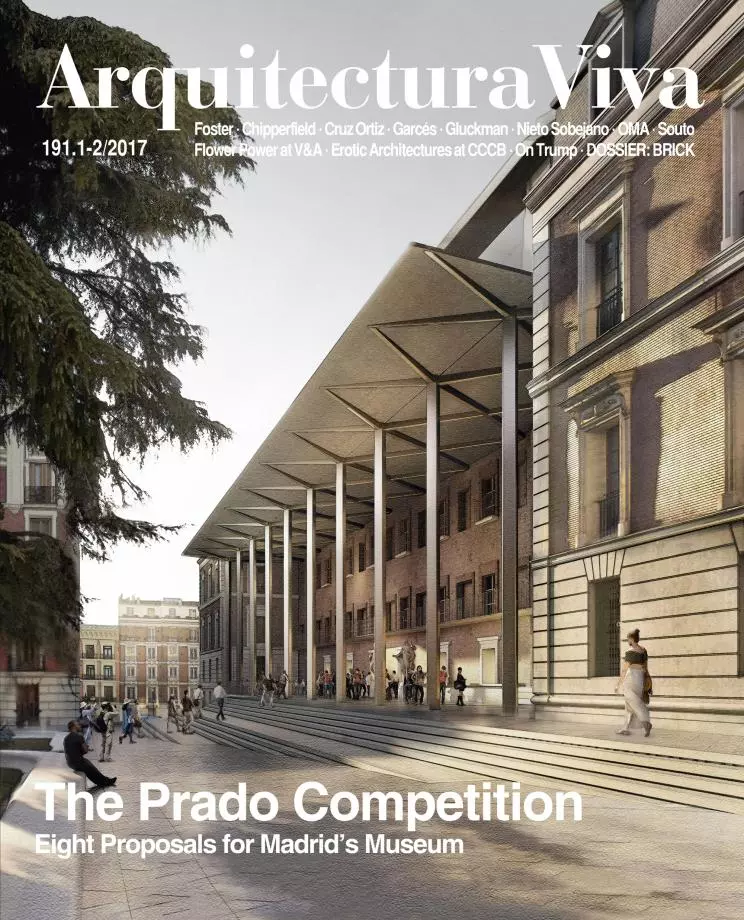

That is, among others, the fascinating story that Beatriz Colomina critically takes stock of in her excellent contribution to the exhibition ‘1000 m2 of Desire: Architecture and Sexuality,’ on view at the CCCB of Barcelona, whose curators, Adélaïde de Caters and Rosa Ferré, have set it up also thanks to the skill of a team of consultants who are very convincing in the subject matter: Esther Fernández and Marie-Françoise Quignard, aside from Colomina herself.

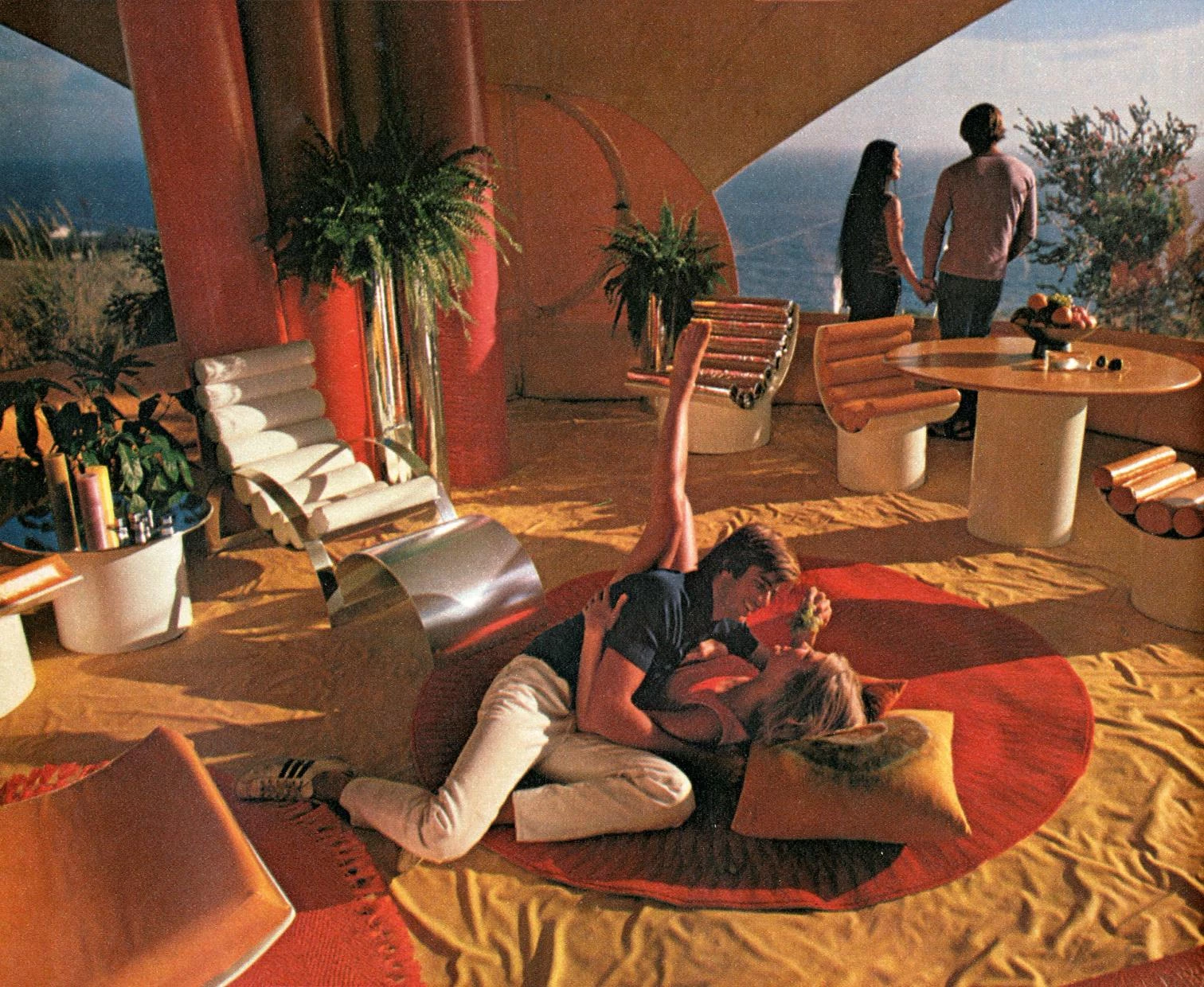

And so, when Playboy hit the stands, everyone thought it was a magazine about women made by men and for men, when in truth it was a masculine claim for what was traditionally a feminine space: the interior space. It’s not in vain that architecture has a strong presence in the publication, complete with famous names, and Playboy males assert their right “to Picasso, Nietzsche, jazz, sex” in their homes. “We like our pad,” said Hefner, as Ehrenreich recalled in the 1983 book The Hearts of Men: American Dreams and the Flight from Commitment. In the final analysis, the magazine’s photographs of naked women were metaphors of the heterosexuality of its promoters and readers. These men had trespassed the metahistoric territory reserved for women, but be careful not to misunderstand: they weren’t gay, and this emphasized once again the entire battery of preconceptions at hand at that moment in time.

In the final analysis, they also rebelled against the cute picture of the happily married couple of the 1950s, with its impositions on the bread-earning family man. What if this supposed privilege was just another false advantage, a privilege as perverse as the precooked meals so in vogue during those years, which, instead of freeing women from having to cook, further enslaved them through the obligation to be more inventive in their homecooking? And what if life outside the home became an inexhaustible source of that stress that Dr. Hans Selye associated with men and their work?

Of course the idea of a house for sex – the successive Playboy mansions inhabited, like the surrealist castle that Breton described, by “women of extraordinary beauty” – still had lots of gray areas: why design for only one woman when we can design spaces in which to enjoy lots of women? But, though as impregnated with inequality as Breton’s, the Playboy project broke the dynamics of private space – that assigned to the “angel in the house” – and made it public, communal, even the quintessential intimate place: that which was meant for sex, and which thus was the kingdom of the male world.

In the Playboy project, moreover, the bed breaks past its role as a mere temple of sex, becoming an office. It almost puts itself in the territory of experimentation, where fragments of desire and even of the story come together naked, even though it remains part of the same masculine narration that has always compartmentalized feminine desire (or its absence), including spatially. In fact, throughout history women have been doomed – as in the discussions about sex that the surrealists engaged in when talking about feminine desires, without inviting any women to take part – to inhabit territories that have been desired by men, subjected to a mapping that wasn’t theirs, yet sought to establish what to desire, when to desire it, and even more, where to desire it. Bedrooms, boudoirs, dressing rooms, bathrooms, or even kitchens; corners in which to catch women in their everyday business, unawares, exposed to the elements; the spell of a desire which has been guesswork – see what one aspires to see – fills male spatial aspirations and imposes on females ones.

Voyeuristic Spaces

This way, women and spaces overlap in masculine fantasies, as what happens with Le Corbusier’s comments about Josephine Baker, when comparing her music with something that can become the expression of “a new age, as with the new architecture.” Or the never executed voyeuristic project that Loos proposed for Baker’s own house: space looking inward, unveiling of private zones presented as actual metaphors of the artist’s insolent body. If the room he designed for his wife, Lina Loos, is a continuous space, with no interruptions or divisions, in which to sink oneself like someone sinking into the female body and getting entangled with it, what the design for Baker has, really, is a certain aftertaste of the exasperation caused by those who see themselves as extreme otherness: do not touch.

So, from the spaces of the voyeur and libertine of 18th-century Paris to the kitchen as a cinematographic spot for wild sex – sex on the kitchen counter, pornographic fantasy as quintessential territory of the “angel of the house,” overflowing with and conquered by urge and passion –, the spaces we inhabit, including those we take to be ‘normal,’ are adjusted, especially to accommodate desire, those male drives and tactics that on the other hand have been dictated, uncontested, by the laws of the modern architectural project, which is quintessentially patriarchal; laws that have hastened to blot out the few diverging fingerprints and exceptions.

The complex historical framework of places for desire and pleasure in architecture thus unfolds in the evocative exhibition ‘1,000 m2 of Desire. Architecture and Sexuality,’ from the sex spaces unleashed in the 18th century – the time of the first impulses of modernity – to those of the 20th and 21st, with certain transformations that ultimately were guises of change. The show presents a mix of literary and theoretical precedents – from Sade to Bentham, a sexual reformist in his way; reproductions of spaces, drawings, prints, and plans that illustrate the contributions of hygienists; the above-mentioned invention of Playboy or the new pleasure routes that propose psychogeography linked to the International Situationist, a mortal enemy, incidentally, of the architectural tyrannies of the modern project: “We have a world of pleasures to win and nothing to lose but boredom,” wrote Vaneigem.

Sex would later leave the house and fill X-rated moviehouses, reproducing here the dark spaces of the long tradition of performed intimacies, but becoming abrupt, solitary, or even anonymous. In the ambiguity of dark rooms, where inside and outside implement each other and cancel each other out, the designed spaces serve as background for fantasies in the midst of a sometimes sordid reality. Virtual spaces in computers, indiscreet games with webcams and their opposite, public spaces without intermediaries, have created a web of desires that no longer need traditional spaces, nor have much influence on them.

So the Situationist lesson – the design of a map of pleasures – is now a cruise à la carte, in real time and on the iPhone screen, that indicates who happen to be nearby… and available; and the searcher doesn’t even have to get to the agreed places, doesn’t have to look, nor require. Liquid sexuality looks for spaces to perform in, spaces which, like the new sexuality, have no fixed location: they are the consolidation of the non-place presaged by Augé. Nevertheless, the question remains: up to what point have these new forms of pleasure had a bearing on modern tradition and its epilogues? To what extent have they modified or revised it? In the end, maybe not much. Which is why Niki de Saint Phalle’s vaginal architecture, which drew people into the Modern Museet of Stockholm in 1966, echoes bright in our memory. Demystified and up to a certain point ironic; unveiled, the fantasies erased, the female anatomy was a mere non-place, a foyer and passageway; public and functional. Owner of herself.