Seven Lamps

The Seven Lamps of the Necessary

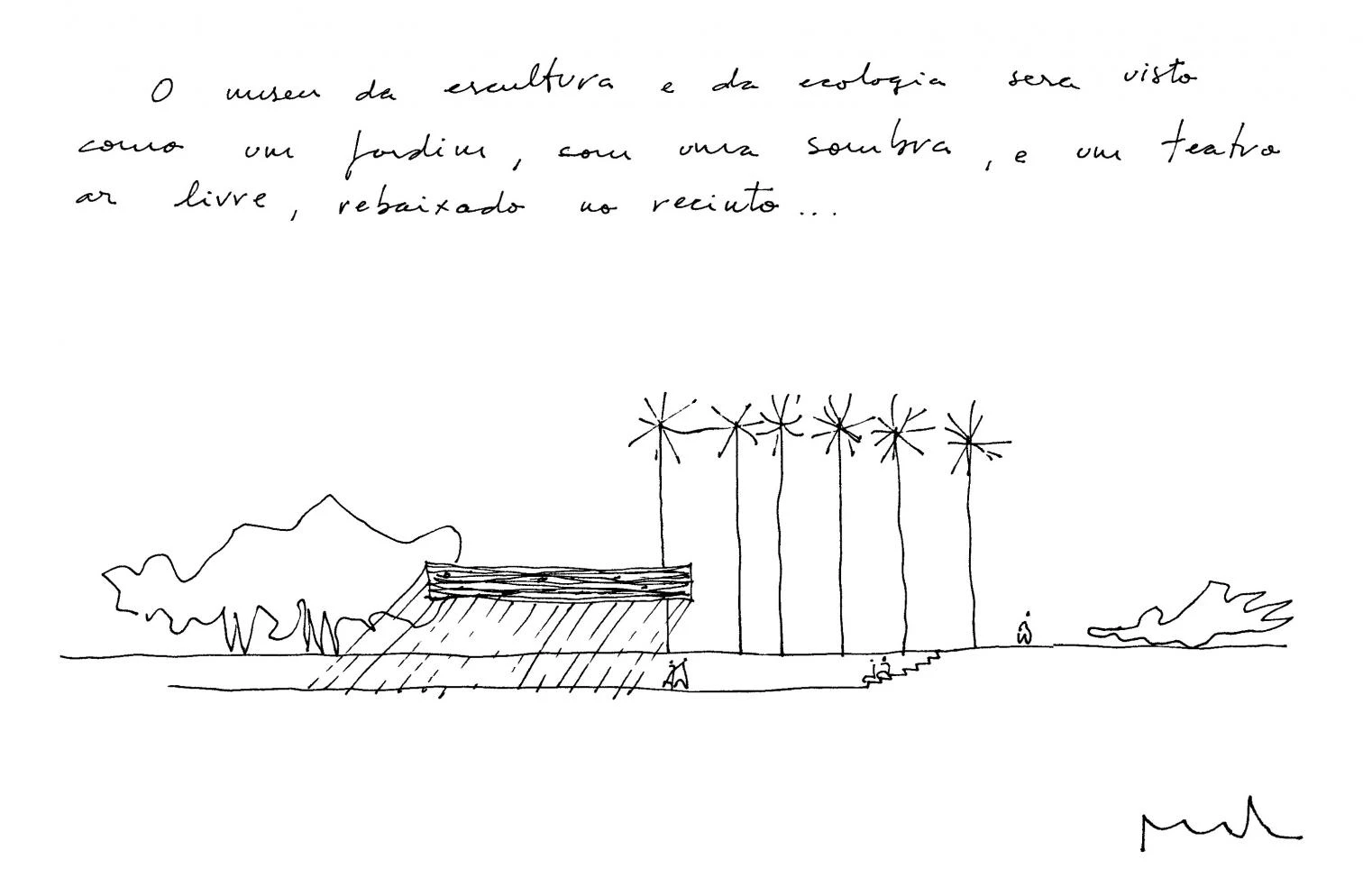

Regarding the main issue of this congress, ‘necessary architecture,’ Luis Fernández-Galiano has suggested summing it up with a quote of Tatlin: “Not the old, not the new, but the necessary.” This definition of necessity can be matched with the contemporary statement of the great Brazilian master Paulo Mendes de Rocha: “Everything that is not necessary becomes grotesque, especially in our time.”

But, before my colleague architects argue this proposition with all the skill of their work and the knowledge of their craft, I shall address the audience with a request that I consider unavoidable: how can we define the concept of necessity in architecture, as, in general, in any other aspect of our spiritual and cultural life?

We always associate necessity with something that presses towards an immediate decision. Something associated with the idea of emergency, low-budget architecture, primary needs: for food, shelter, living conditions. It is no accident that when we surf the web in search of ‘necessary architecture,’ whatever comes out sounds like ‘austerity,’ reuse, sustainability, affordable housing, or even first-aid shelter. Though convinced that iconic architecture is, fortunately, over, and that it is time for architecture to reinstate its status of problem solving, I nonetheless think that we should avoid this identification. In short, I am firmly persuaded that ‘necessity’ is a virtue, not a typology.

But this is only possible if we clear the ground of all the conditionings that in these years of crisis have radically altered our attitude towards architecture, its public role, and its internal laws. We can fight any narcissistic practice of architecture as a private statement of power, and we can also oppose the idea of the architect as a ‘form giver’ demiurge. We can oppose this with a vision of architecture as service to society, a way of thinking the act of building without the excess to which we have been accustomed until now. Architecture as a language without ‘adjectives,’ as Giuseppe Pagano warned from the pages of the magazine Casabella. An architecture conscious of the need to preserve the environment and distribution resources more fairly: in a word, moving its center of gravity from art to necessity.

Ya durante la primera modernidad, Giuseppe Pagano advirtió en las páginas de Casabella sobre la necesidad de frenar el esteticismo con el ‘orgullo de la modestia’ de edificios que fuesen honestos y necesarios.

But we have to understand that the word ‘necessity’ is like a Russian doll; it contains different elements (sometimes synonyms) inside the same shelter: low environmental impact, sustainability, advocacy planning, decision sharing, budget building, and so on. And of course, necessity means going back to the core business of modern architecture, the one that has shaped the social and artificial skyline of the last two centuries: housing, public space, infrastructure. As Adolf Loos clearly pointed out: “The house has to please everyone, contrary to the work of art, which does not.”

This can be easily shared. But the question is still pressing. Is necessary architecture only the one based on primary needs?

The issue is not new. In fascist Italy, when monumentality was the first issue on the agenda, Giuseppe Pagano gave it moral evidence, writing harsh words against Giuseppe Terragni, an unquestionable master of 20th-century architecture. Against the sophisticated (and yet somehow desperate) linguistic experiments leading, for instance, to the Casa del Fascio in Como, Pagano evoked the request for a moderate architecture of modest, honest, necessary buildings. The expression ‘pride in modesty’ became his motto, giving evidence to an idea of the task of the architect addressing his social agenda. Nonetheless, can we really say that the Casa del Fascio is not a ‘necessary’ architecture? Could we dismiss Terragni’s ‘torments,’ his exploitation of his immense talent, as superfluous? Going back to our time, Mendes da Rocha admits: “Unlike many people who are afraid of poverty, I have always been attracted to it, to simple things, without knowing why. Not hardship, but the humility of essential things. I think everything superfluous is irritating.” Can we forget that the reason for our interest in and admiration of his work lies exactly in his ability to translate all these ethical concerns into wonderful masterpieces?

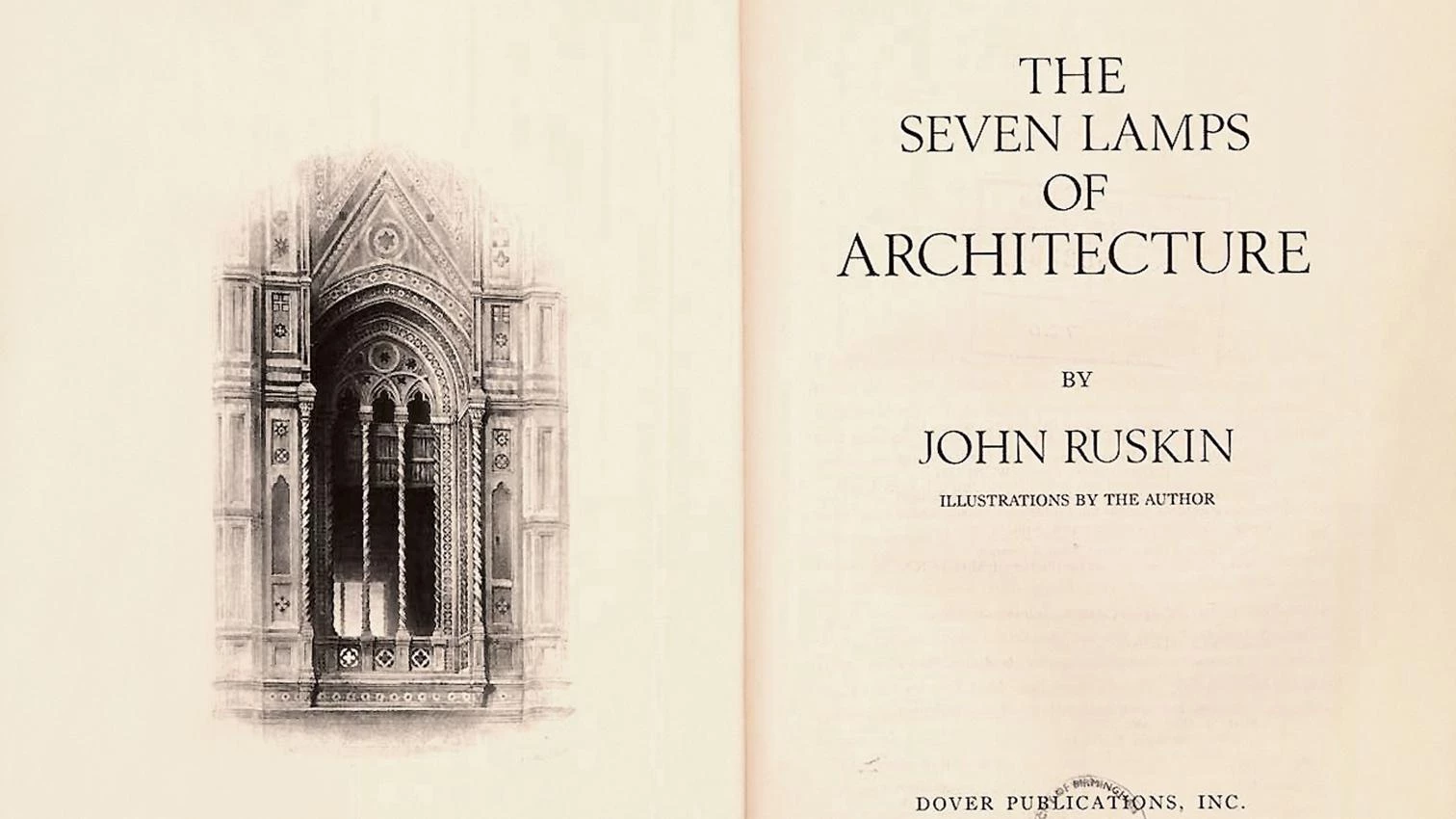

So I would like to launch a modest manifesto for ‘necessary architecture,’ following John Ruskin’s celebrated The Seven Lamps of Architecture, a seminal book where he very clearly posed the terms of the architectural debate in an era strongly conditioned by social pressure caused by the impact of hard industrialization.

Many of his ‘truths’ may seem obsolete for us today, but they are still, in my opinion, a valid ethical and philosophical stance by which to define concepts like beauty, quality, and pleasure as distinctive signs of any architectural enterprise.

Let us think, for instance, about the issue of social necessity – that is, access to shelter for people who have none – or that of public space in a consumerist society that has discredited the same idea of ‘public’ as something cheap, dilapidated, and maybe even dangerous. It is clear that these notions must be reinstated in a proper and pivotal place. But is this enough? Is it enough to reinstate the importance of public space? Don’t we have the need to build a new iconography of public space in the 21st century, one satisfactory enough for people to recognize and appreciate?

From Beauty to Memory

So, I will take the concept of beauty as the first point in our manifesto. Beauty is a right, not a superfluous gift. Housing for the poor doesn’t mean building ‘poor houses,’ but beautiful houses that, starting from a realistic acknowledgment of budget conditions, are the best they can be. They must work perfectly in terms of space standard, of course; they must stay within a fixed budget and offer a perfect shelter for the needs of future dwellers. But this is not enough if we want to avoid a charge of paternalism. Every human being needs beauty as part of his relation with the world.

This leads us to the second issue: quality. Quality is necessary in architecture: without quality, no architecture can be said to be necessary. Quality resists time and its endurance proves its necessity. Quality entails beauty, but doesn’t coincide entirely with it: quality is a result of knowledge and craftsmanship in doing and thinking. An expression of a both rational and visionary attitude: we must keep in mind that sometimes the recourse to science and technology gives the false impression that a building can be designed without a creative hand, without a strong idea behind it.

Quality comes from devotion. Devotion is also necessary in architecture: without devotion, no good architecture is possible. Devotion is a moral attitude that comes from passion, from a commitment to our duty as well as to the need to testify to the necessity of well-executed things. Devotion has a strong religious reference: we are devoted to Gods and to Ideas, and must also be devoted to Architecture. The ardent dedication to a principle is often synonymous with love, and being devoted implies a personal involvement that goes beyond any purely rational motivation. Devotion is a total involvement with its object of love: it is an aim that can be pursued partially.

And then we need desire, because only desire forces us to search for the best. Desire has to do with the future, it is the spring that promotes the vision of what our next future could be: an imagination that pushes the limits of reason, that predicts a better future. Desire possesses the fire of will, but is not purely logic. Desire is the engine that puts architecture on the move.

El discurso, a la vez ético y estético, de Las Siete Lámparas de la Necesidad se ejemplifica bien en carreras como las de Paulo Mendes de Rocha, para quien la «arquitectura no debe ser funcional, sino adecuada».

But how can we distinguish desire from just a whimsical search for the new? Architecture needs truth: truth avoids falling into the fake, into the ephemeral, into a personal fancy. It gives architecture soundness and depth. Truth is necessary, even when it is not shared by common opinion: it is the proof of the necessity of our work; the touchstone for measuring the intensity of our proposals.

And then we need vision, the prophetic quality that goes beyond strict necessity. Because, as we said, necessity is not a value in itself. It is a virtue whose effect we have to demonstrate each time. The avant-gardes who sought to explore the hidden face of modernity felt their predictions and their experiments were necessary, not just a fancy joke.

To avoid this risk, we need the help of memory, our sheet anchor against the danger of shipwreck. Memory is not the worship of the past: it gives us the sense of rooting that we need more than ever if we are to build a better society. Memory is the acknowledgment of our common ground, the antidote to the tyranny of the new at any cost.

Perhaps The Seven Lamps of the Necessary are not enough for us today and we ought to search for some more words with which to define the field of our engagement. But I would like to conclude by borrowing once again from Paulo Mendes de Rocha: “Architecture,” he once said, “does not wish to be functional, but just suitable.”