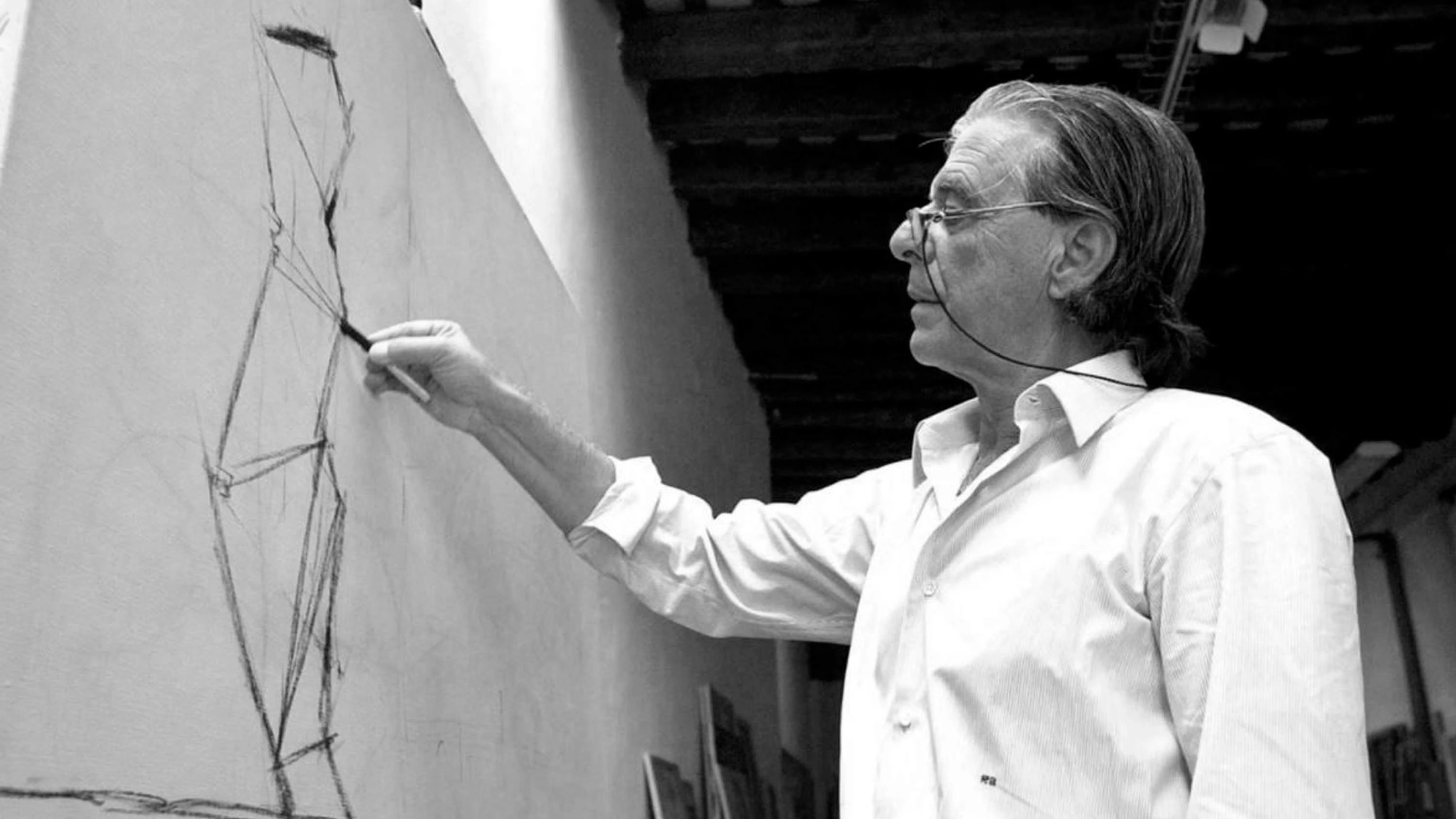

1939-2022

Master of geometry and of the media, Ricardo Bofill was the closest to a star-architect Spain has ever had. That is not a small merit, if one remembers that the Catalan became a star in the years when Spanish architecture was of interest to just a few. Considered, from the beginning, as a child prodigy, the young Bofill received all the laurels and got used to all the excesses, and with the same ease with which he accepted his own genius he raised in the seventies a crop of splendid buildings that in their own way expressed the liberality of the Barcelona of the gauche divine: from the Mediterranean pagoda of Xanadu to the vertical casbah of the Red Wall or Walden 7, that Corbusier-style hippiesque utopia dyed with LSD experienced by some of the best friends of Bofill, like Xavier Rubert de Ventós, José Agustín Goytisolo, Manuel Vázquez Montalbán…

All this success made it hard to think that Bofill would end up working mainly abroad, but the fact is that he moved out shortly after. The admiration he awakened outside Spain was directly proportional to the irritation and perhaps envy he aroused in his compatriot architects. An irritation or envy that became tinged with estrangedness when Bofill abandoned his presumed Mediterranean style, slightly postmodern or postmodern-friendly, to embrace an ironic and unique classicism where triglyphs and metopes appeared alongside mirror curtain wall facades.

The years of classicist mirages were the best of Bofill’s career. Transformed into an international star, he designed everything from his large studio: wineries, perfume bottles, neighborhoods in the ‘third’ world and airports in the ‘first’ and credit cards, as well as monumental and efficient residential developments he gave baroque names like Les Espaces d’Abraxas and Les Échelles du Baroque. In such way that, when his creative star declined, Bofill kept on thinking the same he thought at the beginning of his career: that he was better than all the architects of his generation but much worse than Michelangelo.

This was, of course, another exaggeration. An exaggeration that does detract from the fact that beneath the ashes of Bofill – a master – hide some of the most memorable works of 20th-century Spanish architecture.