Conjunto La Nogalera, Torremolinos (1962-63)

In the last stage of a long career as an architect, builder, and developer, Antonio Lamela vividly remembers advice from his father, an industrialist of the flour-milling and bread-making sector who continues to be his main professional and personal benchmark, and to whose practical intelligence he attributes the success that has accompanied him from the start. The paternal factory was in Carabanchel, now a modest district but at that time a village on the outskirts of the Spanish capital, and this was the setting of his comfortable childhood and also of the difficult years of the Civil War. After schooling at the Salesians, his desire to pursue technical studies led him to architecture, for which he enrolled at the then very domestic Madrid School, where he was dazzled by the young professor Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza, and where he stood out as the most active member of his class.

Residential Exercises

Still a student and with stimulus from his father – who would act as capital-providing partner – Antonio Lamela ventured to raise a building with all phases of the process under his control, from looking for a site to drawing up the project and on to actual construction and sale of the property. The result of this discipline is perhaps his best work, the rational and elegant apartment building at O’Donnell 33, which would be a testing laboratory for all his subsequent work, and from 1958 on, the location, on the sixth floor, of his home and office. Some years later he repeated the format, again with considerable success, in another rationalist work, the dwellings he developed on what was then called Avenida del Generalísimo, the grand north-south axis of a Madrid that was beginning to grow vigorously, and the 1950s ended with Motel El Hidalgo in Ciudad Real, a road inn for travelers and hunters that drew inspiration from American models and which he carried out in association with José Meliá, a hotelier with whom he undertook major projects connected to the incipient tourism of Spain’s coasts and archipelagos.

Rational Relax

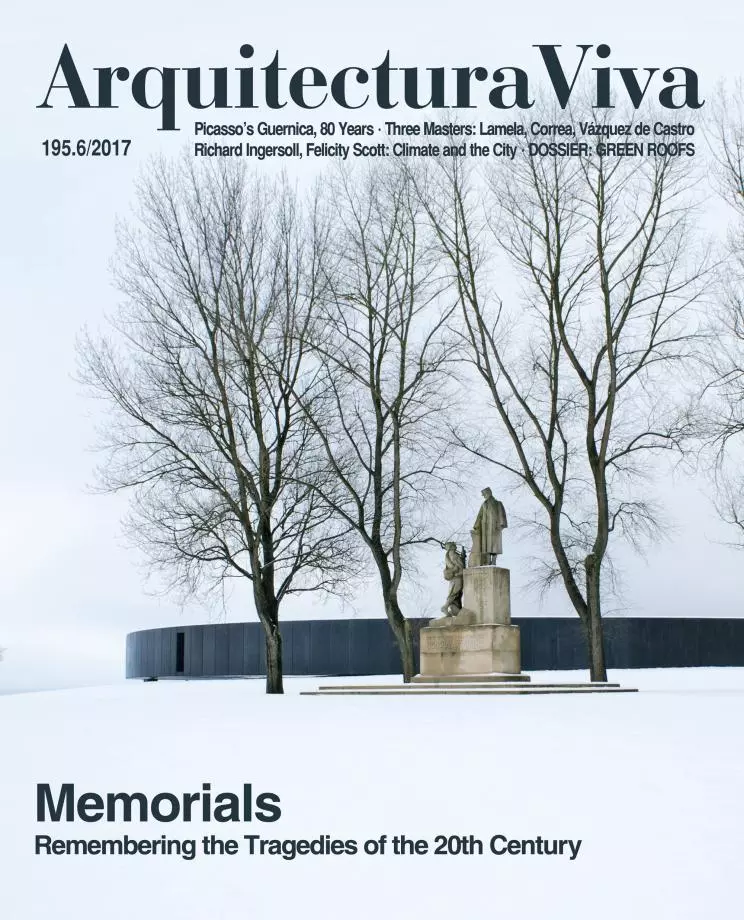

In Torremolinos, for example, Lamela built for Meliá the Hotel Tres Carabelas, a splendid work that reinterpreted the modern language he had learned from Mies and Neutra, and which he extended in laconic, austere residential complexes like La Nogalera and Playamar. The same goes for Mallorca, where the early 1960s saw the construction of tourist apartments, such as La Caleta in Palma and Rocamarina in Cala d’Or, in both of which the proprietor of the land acted as co-developer, and which were followed with equal success by projects in the Costa del Sol: all of them architectures of leisure, early examples of what could be called ‘rational relax.’

Building the City

But Madrid was where Lamela raised his most important works, on a scale and with a visibility that surely made them part of the image of the city. Especially important was Hotel Meliá on Calle Princesa, a complex that included apartments and offices on land purchased from the House of Alba, adjacent to the Liria Palace grounds; the Galaxia ensemble, an experience in urban design on the site of an old perfume factory; the Torres de Colón, whose structure designed by the engineer Javier Manterola made the floor slabs hang from the top of the towers, making them a technical feat and a landmark in a highly visible place; and the Pirámide, again on the Castellana axis, where the requirement to set buildings back from the avenue gave rise to an iconic form.

Torres de Colón, Madrid (1967-74)

Serving Multitudes

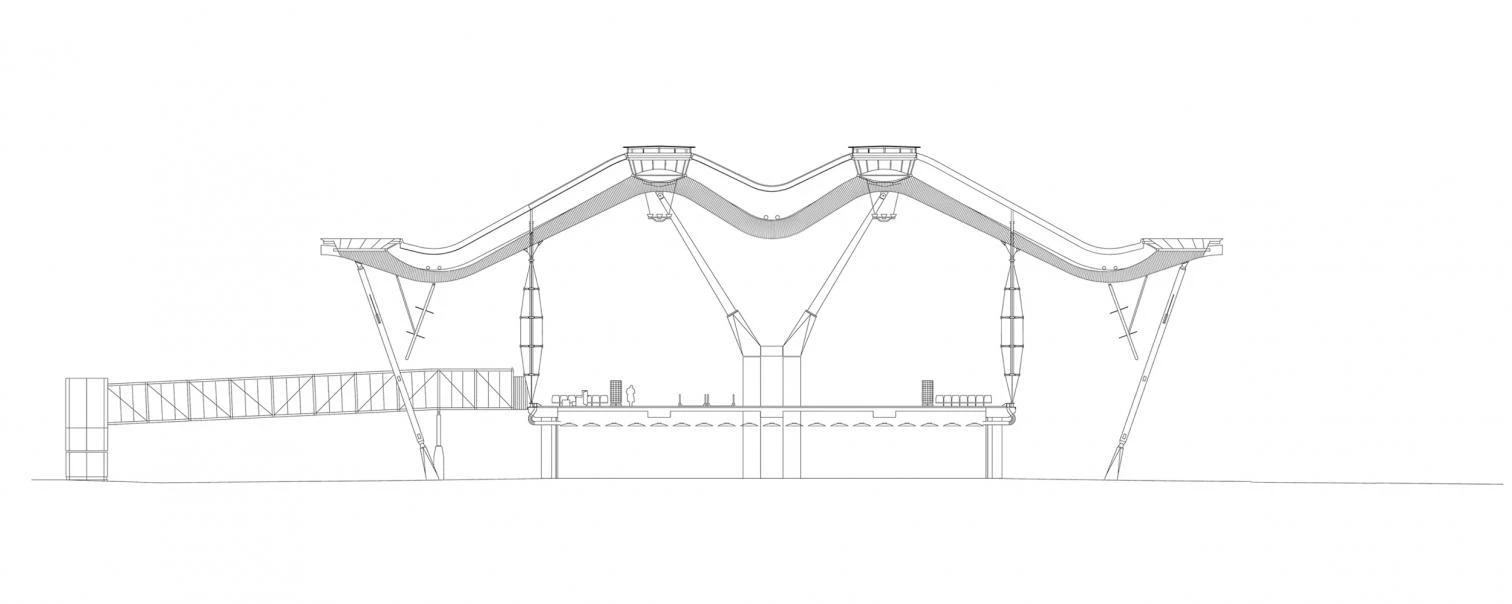

The Spanish capital would also be the location of some of the firm’s largest and most symbolically significant commissions in the post-Franco years: Santiago Bernabéu Stadium, which Lamela – Real Madrid member number 59 – enlarged and renovated in two successive stages, starting in 1988, for club president Ramón Mendoza; and Barajas Airport, whose terminals he renovated and whose impressive T4 he built, beginning in 1998, with the British architect Richard Rogers, stunningly crowning the emblematic gate into the city with a colorful branching structure supporting bright weightless-looking bamboo roofs. This experience with sport and airport architectures would lead the practice to the international scene with projects, among others, for a stadium and an airport in Poland, both of which benefited from the know-how acquired in the Madrid jobs.

Though the core of his oeuvre is in Madrid, with works like the Torres de Colón or Terminal 4 at Barajas - the latter in collaboration with Rogers-, Lamela also built tourist complexes on islands and coasts.

A Choral Enterprise

Transformed into a choral enterprise, joining Lamela’s signature with the talent of new generations, the architect’s office, now run by his son Carlos, continues to produce works of great efficiency – some friendly, such as the one for the Reina Sofía Foundation’s Alzheimer’s Disease Project, where color and plants are the protagonists; others drier and more refined in language, such as the corporate headquarters of the John Deere multinational, with its folds of shifting reflections; and some with the austere sobriety of the Leitner Building, where the firm has its current offices, from which it continues the founder’s versatile work while he pursues the personal passions which once led him to propose what he called ‘geocosmoism,’ create a Spanish chapter of the Club of Rome, and defend the need for architects to work with a global perspective. [+]