Barcelonian through and through but with family origins in Comillas and Jerez, Federico spoke Spanish at home and his childhood in the Philippines gave him an early command of English and a cosmopolitan mindset. At twelve years of age, the Spanish Civil War sent him to boarding school in England for two years. He also attended Jesuïtes Sarrià, where he struck a friendship with his future inseparable partner, Alfonso Milà i Sagnier. With him he decided to study at the Barcelona School of Architecture, where he stood out as a draftsman. After graduating, Correa established what was to be a lifetime relationship with Oriol Bohigas, with whom he began to see architecture as an intellectual and political activity, in tune with the Italian circles of the likes of Gardella, Albini, and Rogers.

The Cadaqués Houses

His first professional steps were taken in Cadaqués, where he and Milà built houses for friends or relatives with an exact interpretation of popular architecture, learned from José Antonio Coderch, that resulted in admirable adaptations to both the picturesque seaside town and its landscape. One was the Villavecchia house, at once modern and vernacular in its compositional freedom. Another was the Rumeu House, built for a brother-in-law of Milà, where the use of stone shaped it like a piece of the landscape. And finally his own house, with an arrangement of uses that reflected the informality of summer vacations.

The Challenge of Scale

The firm of Correa and Milà – where the partners took on complementary roles, with Federico minding the office and Alfonso dealing with clients and construction sites – soon had a change of scale, spending the 1960s designing factories and residential buildings of large dimensions and high visibility. The Montesa factory in Cornellá, a property of the Milà family, was a first experience in industrial architecture, executed with moderate spans and a prefab facade that turned out less impermeable than expected, for which reason in the Godo y Trías factory in Hospitalet the architects decided to use brick, which performed more predictably and also harmonized better with the surrounding modernist constructions. This factory received more critical acclaim than their first high-rise work, the Monitor Building in Barcelona, a residential development for a family connected to the Milàs which the architects carried out to less success than their other, simultaneous landmark in the city, the Atalaya Building on the Diagonal, where they managed to interpret the residential program and the artificial stone claddings with the Milanese sophistication of authors like Figini and Pollini, brought close to the Catalan debate by Correa’s trips to Italy.

Interior Design as Architecture

The hotline with Milan aroused their interest in design and interiors, and it was Vico Magistretti’s friendship with Olivetti’s director in Barcelona that led them to design several stores for the firm, where they gave the limelight to the machines with the shop windows raised to eye level and the impecable white of the interiors. This activity also yielded two restaurants that were a great success among Barcelona’s intelligentsia, promoted by Alfonso Milà and Leopoldo Pomés: Flash Flash, decorated with elegant photographs by Pomés that quickly became pop icons; and Il Giardinetto, which Correa imagined as a meadow covered with a frond of chestnuts, making name and ornament resonate.

Innovation and Memory

The change of regime after Franco’s death allowed architects who had led political opposition in the university – such as Bohigas and Correa – to take on public commissions, and in the 1980s the office of Correa and Milà was able to work on the historical city combining innovation and memory. This was the case in the redevelopment of the Plaça Reial, where they gave pride of place to palm trees and tried in vain to stimulate spontaneous social contact through urban furniture, attesting to the utopian dimension of Spain’s transition to democracy. Less sociological was the project for the seat of the provincial government, where the architects tackled a difficult site with intelligence, in dialogue with an existing building by Puig i Cadalfalch. And exceptionally daring was the apartment building on Passeig de Gràcia, where there was no hesitation to use mimicry in expanding a work by Guastavino, once again proving the ductile nature of their talent.

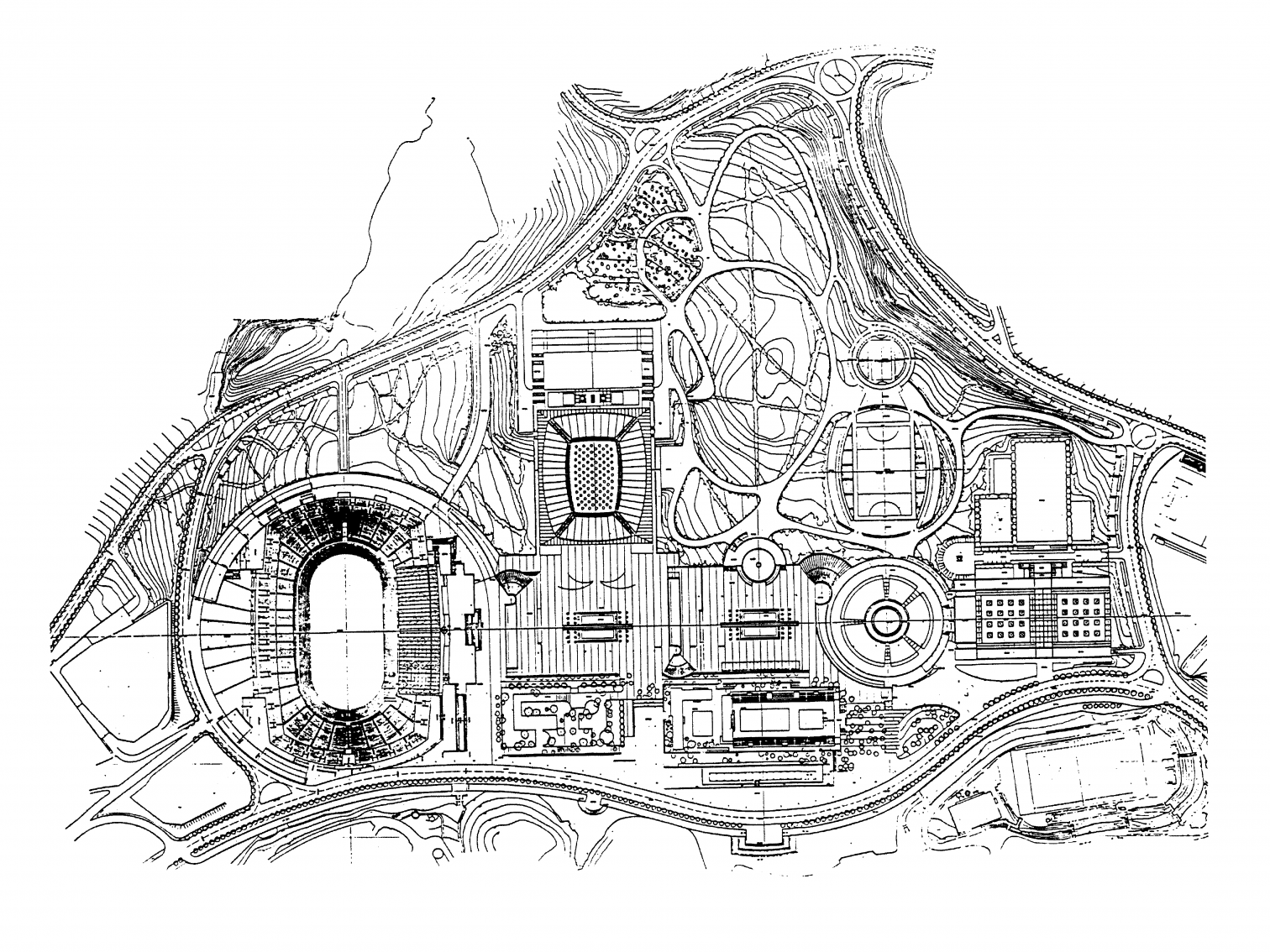

Return to Origins

The Barcelona of the annus mirabilis 1992 had Correa and Milà among its protagonists. Their practice – after winning with Margarit and Buxadé the competition for the Olympic Ring, where buildings like Isozaki’s Palau would go up – collaborated with the Italian Vittorio Gregotti in renovating the Olympic Stadium, venue of the most significant events of the Games. It was not Olympic Barcelona, however, but inner Catalonia, that would harbor Correa’s last major work, the Episcopal Museum of Vic, home to a splendid collection of Romanesque art, where the architect combined medieval and modern in the free arrangement of windows, as he had done in the Villavecchia House in Cadaqués, somehow returning to where he started and closing the circle of a career that has orbited around the city he helped make and which made him, Barcelona. [+]