In 1964, Franco’s regime launched a large-scale publicity campaign under the motto ‘25 Years of Peace’. It was a cemetery-like peace, however, that concealed the truth of two wars: a war of subjugation directed at the population, which had gradually pacified as the system settled; and a war of annihilation waged against the landscape that broke out around then, in the wake of economic development and migratory movements. The state police repressed the population, although with diminishing virulence; and real estate operations destroyed the landscape, but in this case with an increasing pace. Now, on the occasion of the twenty-fifth year since Francisco Franco’s death, it is fitting to ask if there has really been a significant change in these tendencies. Fortunately, democracy has indeed limited political repression, in fact to the point that in some juvenile brawls it is the population that represses the police, and no longer the delinquents who hide their faces but the actual policemen, always masked or obscured in press images. But alas, democracy has also increased the exploitative devastation of coastal spots and natural enclaves, giving rein to a massive campaign against the landscape that has reached caricatural extremes in some seaside municipalities.

The incompetence of the administration, economic greed and speculative development have brought about a destruction of the coastline by real estate that reaches caricatural extremes along the Andalusian Costa del Sol.

It would be nice to dismiss the popular mayor of Marbella (a shady character, involved in countless lawsuits which refer to his activity as both a local politician and a developer) as an isolated tumor, one extractable through judicial means. Sadly, however, Jesús Gil and his newly created political party are only the most uncouth expression of a wide-spread evil that has turned the post of town councilor in charge of urban planning into a coveted political booty, for it is here that the management of public funds, the voracious financing of parties and the greed of private interests all come together. Of course the southern Costa del Sol has always had the appearance of a somehow lawless territory, with that mix of sheikhs and gangsters that made it look like an offshore fiscal paradise on firm ground. But with its spread to Ceuta and Melilla, the two Spanish cities in the north of Africa, Gililand begins to imitate the fiction of Julian Barnes, and the autonomous Utopias of the two African cities come close to the independent thematic redoubt that the island of Wight becomes in the British writer’s England, England; while Jesús Gil (who is mayor of Marbella and president of the Atlético de Madrid football club at the same time) begins to caress the same wild ambitions that drove Robert Maxwell or Rupert Murdoch, the magnates Barnes modeled his character after.

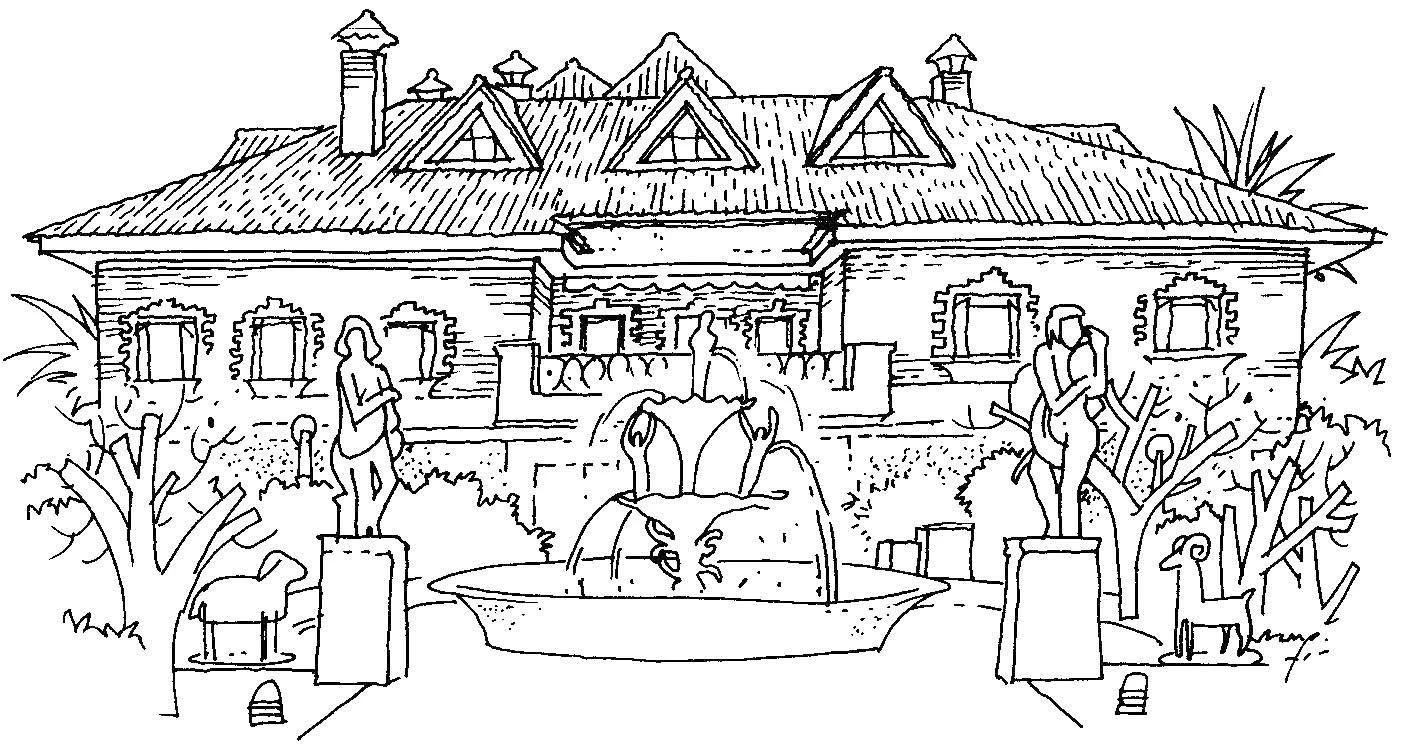

The figurative populism represented by seafront developments like Puerto Sherry, on the Cádiz coast, can also be found in the private residences of Spanish politicians, be them mayors of tourist areas or prime ministers.

Nevertheless, Gilism camouflages the real comatose situation of the landscape. Its methods are so coarse, its results are so vulgar and its leader is so buffoonish as to draw attention away from a unanimous affliction, so much that we now deem the situation critical only if it shows Gilisymptoms. In the absence of gold chains, suitcases stacked with bills and shows of bravado, we think the disease is under control. Yet just as damaging to the landscape are administrative incompetence, inventive accounting and favor dealing, activities carried out by routinary functionaries, respectable councilors and anonymous businessmen. In the past months we have seen this underwater world of corruption surface in the Balearic and Canary islands, and after a summer with Ceuta and Melilla in the headlines of newspapers, this autumn has the iceberg show ing its tips along the Atlantic arc of the province of Cádiz, from Sanlúcar de Barrameda through Barbate and Zahara de los Atunes to Tarifa. But as usual the alarms go off late, and for the wrong reasons. For contrary to what is affirmed, this is no municipal evil in need of regional recipes.

Jesús Gil

Adolfo Suárez

Natural heritage, like historical heritage, cannot be protected on a local level: proximity multiplies pressures to intolerable heights. And that the regional sphere can give the landscape what the municipal domain denies it, is exceedingly doubtful. The Cádiz coast has deteriorated to an advanced degree right before the eyes of Andalusia’s autonomous government, the Junta, with its indifference or acquiescence, and similar things can be said of other regional governments of Spain. Only obsolete residues of the old centralized State – including large sleeping estates of the Army – remain intact as archaic redoubts, but new rulings involving military properties are ensuring that these unproductive lands are fed into the real estate grinder of profiles and landscapes. In ephemeral times of irresponsible euphoria we may reckon that a better visual culture of our leaders would protect the landscape from mercantile and thematic abduction, but a quick look at the homes of our politicians shakes us back to reality.

Even if greed were to disappear by magic, in Spain today it is useless to claim (using the words of the Spanish Republic president Manuel Azaña) peace, pity and pardon for the landscape. In 1874, the Scott Robert Louis Stevenson wrote a short text entitled On How to Enjoy Disagreeable Places. Recommending it as a read would perhaps be more efficient than this jeremiad.

Felipe González

José María Aznar

You’ll know them by their houses

Politics and economics are etymologically related to the city and the house, but the politicians and economists who are our leaders show small interest in either one or the other. We cannot expect them to share the architectural passion of George Washington, whose house on Mount Vernon crystallized a new model of residence, or the talent of Thomas Jefferson, whose Monticello mansion brought neoclassical architecture to America. In Spain, Philip II and Charles III were perhaps the last rulers who aspired to the Solomonic status of a wise builder king. Today our royal family lives in a renovated small palace and seems more interested in naval than in residential construction, while successive prime ministers have occupied another modest palace; their manie de bâtir, if any, materialized only in the hypertrophic growth of offices for presidential staff – the only thing distinguishing democracy’s La Moncloa from the military laconism of Franco’s El Pardo. But the private residences of prime ministers throw a light on each one’s con-struction preferences that helps us understand their shared anorexia in esthetic matters. The slate roofs of Adolfo Suárez at La Florida and the vernacular severity of Leopoldo Calvo-Sotelo at Somosaguas are as characteristic of their owners as the cheerful Rossian rationalism of Felipe González in Pozuelo. But nothing would have prepared us for the thematic shock of José María Aznar’s recently purchased Levitt House at Monte Alina, which comes straight out of a Disney TV series. Only when we set it against the pompous naïf ostentation of Gil’s Marbella mansion are we forced to admit that, indeed, any situation can change for the worse.