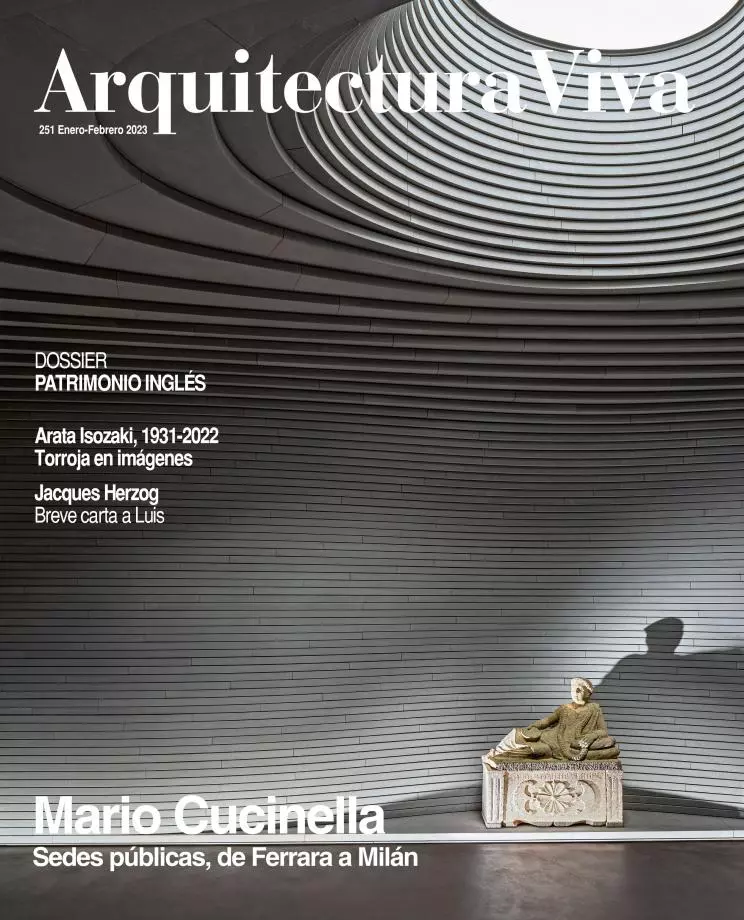

Past futures

Heritage Interventions in England

David Chipperfield Architects, Royal Academy of Arts, London

Architects are generally trained in the modern idea that their job is to build a new world, so they try to raise new buildings or even design entire parts of cities. But the profession today is more and more about building on what is already built, about incorporating into the project the often powerful, and also sometimes uncomfortable, traces of the past.

The incorporation of these traces of history can be carried out in many ways, depending as much on the architect’s disposition and his vision of the past, as on the physical state of the preexisting. Occasionally a trace of the past is so powerful that the architect can only address it with the attitude of deference that scientific restoration nowadays takes pride in. When this happens, the professional – almost always supported by a multidisciplinary team – complies with the classic motto of ‘fixing, cleaning, and giving splendor’ to the monument, even though the respect for the relic is tinged with all manner of ideology regarding what a monument is and up to what point it rightfully ought to be worked upon. In other cases, the mark of the preexistent is not as deep or as strong, whether because the building is not that old or not that well preserved, or because only bits and pieces are left of it anyway. It is in such situations, perhaps, that architects feel most comfortable, as here there is more and greater leeway for intervention, and the potential engagement with the piece of heritage can take the form of creative distance and frank dialogue between old and new.

To look into the challenges of working upon existing constructions, a field that gets more and more demanding as well as increasingly relevant to an evolving profession, this dossier of Arquitectura Viva presents four examples located in a country that has been a key pioneer in the matter of reflecting and acting on heritage: England. Each case illustrates a different approach. The intervention carried out by Hugh Broughton Architects at Clifford’s Tower in York applies a strategy of inserting new amid old that results in a serene conversation between geometries and finishes. On the other hand, while the library of Magdalene College in Cambridge, a work of Niall McLaughlin Architects, is conceived like a typological and material mirror of the historical building beside which it has gone up, the same university campus’s new Homerton Dining Hall by the firm Feilden Fowles is the outcome of creatively interpreting the tradition of colleges and that of Arts & Crafts. Finally, in the Sands End Community Centre by Mae Architects, in the English capital, dialogue is established not so much with an older building as with a preexisting environment, South Park in Fulham, where a delicate pavilion now rises with a shape and a palette of materials that is evocative of the heritage of greenhouses.

Robert Venturi & Denise Scott Brown, Sainsbury Wing of the National Gallery, London