Roller Coaster Origami

The Yokohama terminal by Zaera and Moussavi is a colossal wavy construction finished in time for the 2002 World Cup, held in Japan and Korea.

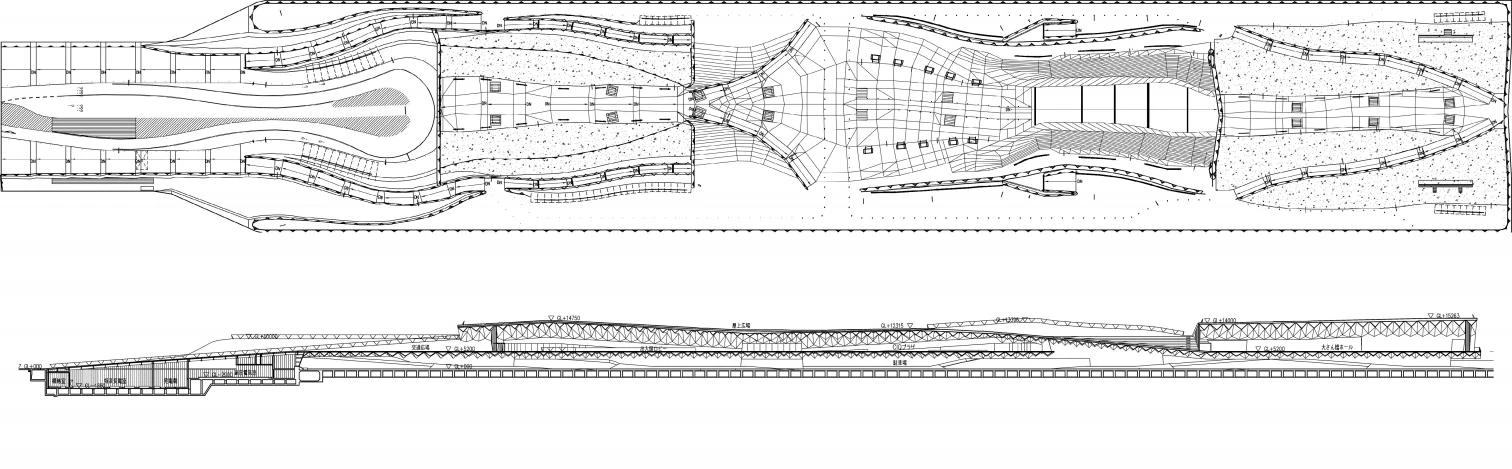

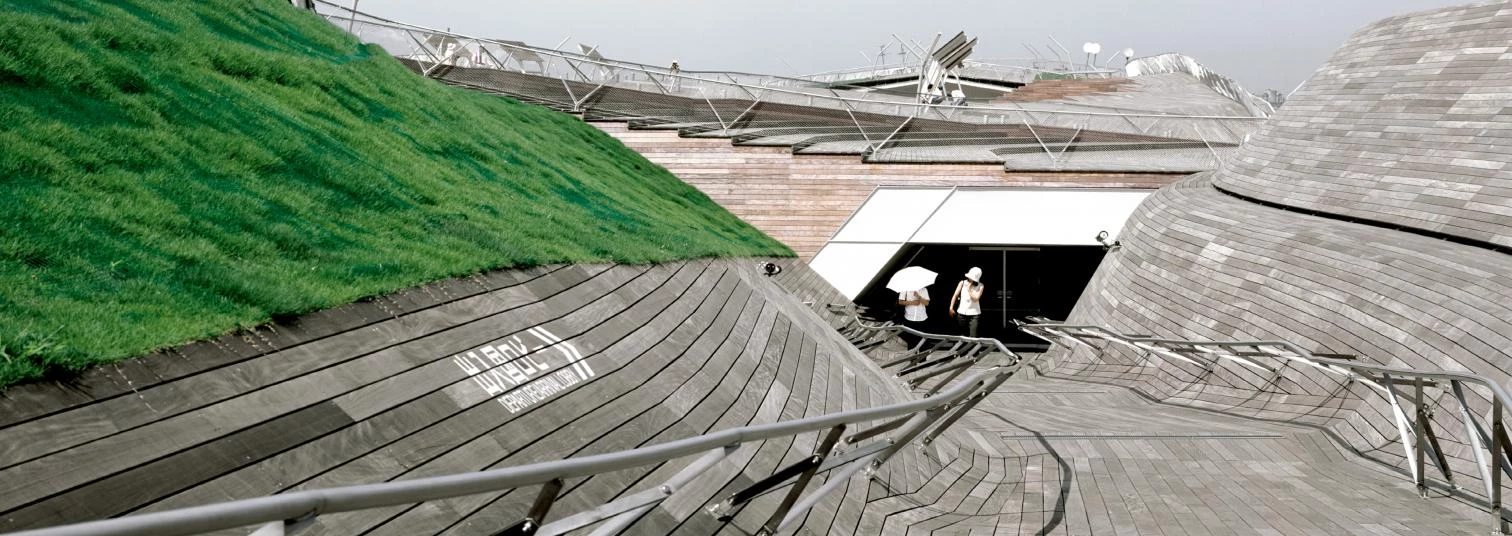

The emblem of the World Cup is a wharf. The holding of the World Soccer Championship in Japan and Korea has occasioned the construction of 17 new stadiums in both host countries, but the most innovative work is perhaps a transport building, Yokohama’s maritime terminal. Designed by a partnership of architects, the Iranian Farshid Moussavi and Madrid’s Alejandro Zaera, the terminal began operations on the 2nd of June, as much for cruiser line traffic as for the ferry which, at least while the games were ongoing, has connected by sea two countries whose relations in the past have not always been as fluid. The work that symbolizes such inclination for communication is a colossal platform 70 meters wide and 420 meters long that pushes into Yokohama Bay in such a way that four cruisers can moor at the same time, over which a unique construction of steel, glass, and wood presents itself as both a terminal for passenger ships and a public recreational zone whose undulating relief extends Yamashita Park.

The first port of Japan that cleared its docks to foreign ships has built today a significant symbol of the country’s renewal and openness: a 70 x 420 meter wharf for the mooring of cruisers that is also a public park.

With a population of over three million, Yokohama is Japan’s third city, but the proximity of the giant metropolitan area of Tokyo has blurred its personality, which is closely associated to the country’s contemporary history: the opening of its bay to foreign vessels in 1859 initiated the westernization process of Japan and it became a port of entry of modern ideas and techniques. In past years the port city has tried to assert its independence from Tokyo with the refurbishing of the old docks for public and commercial use, with the construction of buildings like the Landmark Tower, a skyscraper designed by the American Hugh Stubbins which is currently the archipelago’s tallest, and most recently with the in-auguration of the international maritime terminal, whose extraordinary profile of artificial landscape promises to become an icon.

When executing the wavy surfaces of the project, the system of warped slabs was discarded in favor of another of box-beams with transversal trusses clad in steel sheet whose folds evoke traditional Japanese origami.

The wharf is the symbol of several things at once: a tradition of openness to the world, a disposition to cooperate with the neighboring country, and the strengthening of ties that a sport competition is wont to promote. It is not the first time that a building with an infrastructural function in communications or transport becomes the image of an international sports event: Norman Foster’s Collserola Tower represented the media nature of the Barcelona Olympics better than the actual sport venues, and together Santiago Calatrava’s Alamillo Bridge and Cruz & Ortiz’s Santa Justa Railway Station e-pressed the acceleration of exchange propelled by the Seville Expo more eloquently than the forest of pavilions erected on Cartuja Island. Compared by some, for its emblematic uniqueness, to Saarinen’s TWA terminal in New York, Utzon’s opera house in Sydney, or Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, the maritime station of Yokohama surely has more in common with Kansai Airport, built by Renzo Piano on a man-made island in the bay of Osaka: another port of entry to Japan designed by a westerner, and with geometries as complex as the logis-tics of the operation.

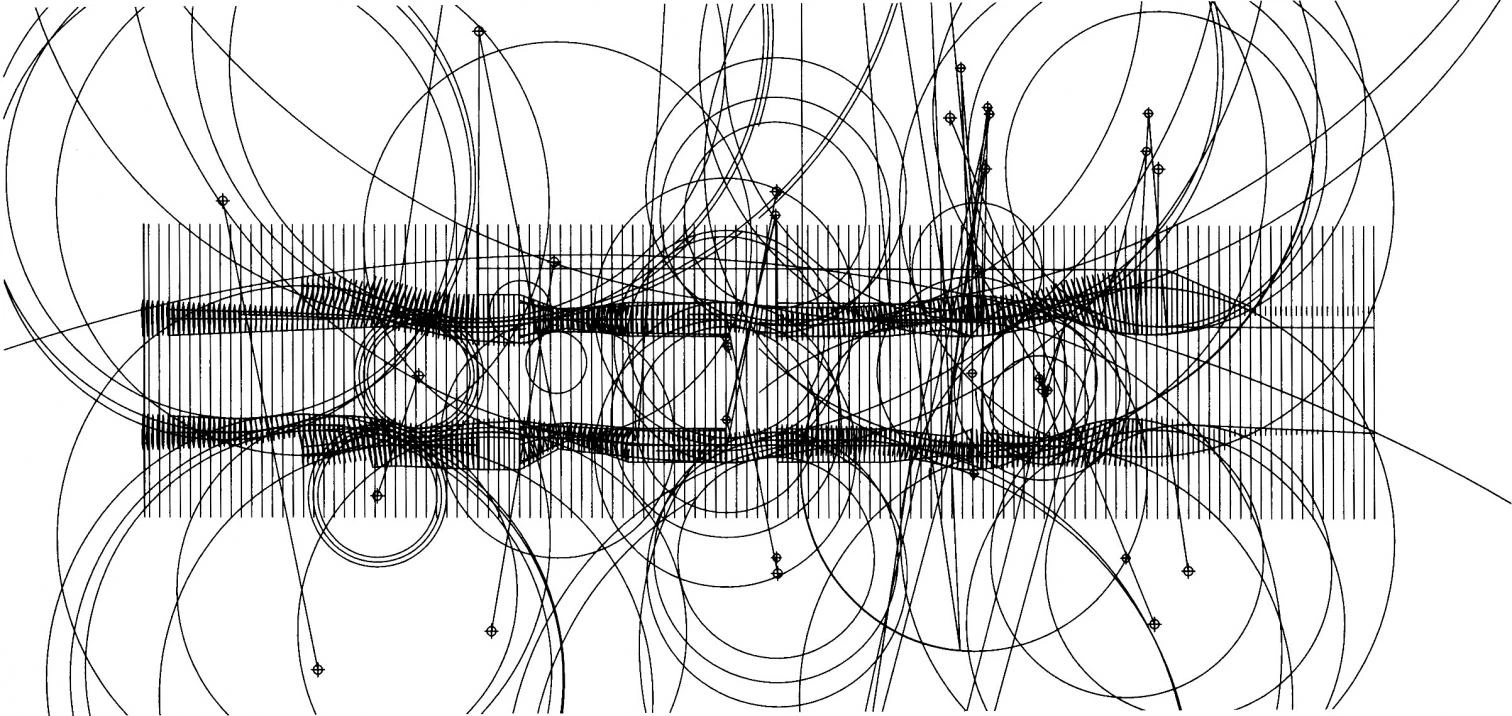

But none of these references is as pertinent as mention of Rem Koolhaas. Both Moussavi and Zaera studied under him at Harvard, to subsequently work in his Rotterdam studio. Koolhaas’ characteristic ‘free section’of warped surfaces was used in the terminal project, and his being in the jury of the 1995 competition was instrumental in the selection of the tandem, then only 30 and 32, respectively, and by then based in London as teachers in the Architectural Association and partners in a small studio significantly named Foreign Office Architects. Foreigners in Great Britain, just as they had been in the United States and the Netherlands, and just as they would be in Japan starting 1999, when the FIFA’s decision to hold the World Cup in Asia for the first time rescued the project from the limbo it had been thrown into by the crack of the Japanese stock exchange, by doubts regarding the need for a work of that scale, and by lack of confidence in the capacity of inexpert architects to carry out a construction of such complexity.

Installed in Tokyo with a reduced team of 14 very young architects – Japanese sherpas to serve as guides in the craggy and unfamiliar local terrain, and Spanish gurkas to clear the way in the foliage of protocol, guidelines, and contracts – Moussavi and Zaera intelligently aligned with Structural Design Group, an engineering office headed by Kunio Watanabe, and the final project jointly drawn up by FOA and SDG radically revised the structural naiveté of the competition proposal. Discarding the unfeasible original scheme of warped floor slabs sustained by undulating steel sheets, they designed a mixed system formed by two large box-beams that crawl longitudinally through the terminal, and a secondary transversal structure of steel folds that span the space between beams and cantilever on both sides: two dorsal spines that also serve as ramps connecting the different levels, vertebrating the building functionally and structurally, and which because of their unique geometry would be built using the same procedure as roller coasters; and a rib-like assemblage of steel trusses lined with metal sheet whose folds echo Japanese origami.

This structure, complicated not so much in con-cept as in its tortuous geometry, covers the parking area and the very horizontal transit concourse, shaping the warped roof, where wood combines with grass to form a public space with itineraries delimited by railings. Both the patches of grass –required for the terminal to be officially considered an extension of the neighboring park – and the proliferation of railings that break up the upper plaza into routes are elements far from the clear continuity of the original project, which also suffered on account of the problematic negotiation between the wooden boards and the undulations of the roof, whose double curvature seems to admit only a homogeneous cladding. Alejandro Zaera stresses that the building’s final form is more the result of the construction process than of any a priori aesthetic decision, and the difficulties of construction have indeed determined many formal choices. But it is also true that the process has been subjected to rather twisted initial conditions that make it unduly contrived. The final result oscillates between the painful muscular stillness of Michelangelo slaves and the uneasy swaying of athletic marchers..

In any case, the very materialization of an object of such complexity, visibility, and scale in itself constitutes a professional feat and symbolic achievement that makes Zaera (recently appointed Dean of the Berlage Institute) the most important Spanish architect of his generation: an intellectual and critic possessing the analytical refinement shown by the ‘scientific autobiography’ published by installments in the Japanese magazine a+u; and a gifted designer and organizer whose talent and ambition comes to the fore in this hybrid of naval construction and landscape architecture that now extends over Yokohama Bay its mannerist mix of Japanese origami and roller coaster.