A dream factory, the virtual architecture of the media has not put an end to the material architecture of the city, but has managed to transform it into an illusionist fake. Victor Hugo’s prediction “ceci tuera cela” proved unfounded, and his novel failed to replace the Notre-Dame building in the collective imagination. The politicians and entrepreneurs who lead the Dotcom revolution today predict the supremacy of the net at the same time that they promote tangible architectures, and their imaginary constructions become metaphors or placebos of the digital universe. Blurring the lines between real and virtual, private and public, domestic and urban, these architectures.com share a trivial futurism that feeds on cartoon or videogame imagery, and a grandiloquent megalomania that flaunts cost and scale. From Tony Blair’s Millennium Dome in London to Juan Villalonga’s Ciudad Telefónica in Madrid, and from Bill Gates’s house in Seattle to Michael Dell’s in Austin, everything about these colossal projects speaks of technical exhibitionism and esthetic vacuity.

Designed by the Richard Rogers studio, the gigantic Millennium Dome in London’s Greenwich Peninsula has failed in its attempt to symbolize the optimistic and dynamic spirit of Blair’s cool Britannia.

In the British case, the fairground tent at Greenwich was more than a routinary supply of entertainment for the masses through which the State legitimizes itself, the same “panem et circenses” Juvenal reproached the decadent Rome of his time. For New Labour and its ideologue, the Machiavellian Peter Mandelson (now in charge of Irish affairs, after having atoned for his mortage sins with a short confinement in the political purgatory), the Millennium Dome was a project meant to empower the nation with a new identity by boosting citizen self-esteem and the United Kingdom’s world image. But the £800 million spent on the planet’s vastest roof (designed by Mike Davis of Richard Rogers Partnership in conjunction with a dispersed army of designers and architects including Branson & Coates, Zaha Hadid or Eva Jiricna), has only given Blair’s cool Britannia the embarrassment of watching the media bubble deflate – the same bubble that til opening day had been blowing hot air into a gaseous experiment of thematic pedagogy –and this New Age Disneyland has gone asail under somber omens.

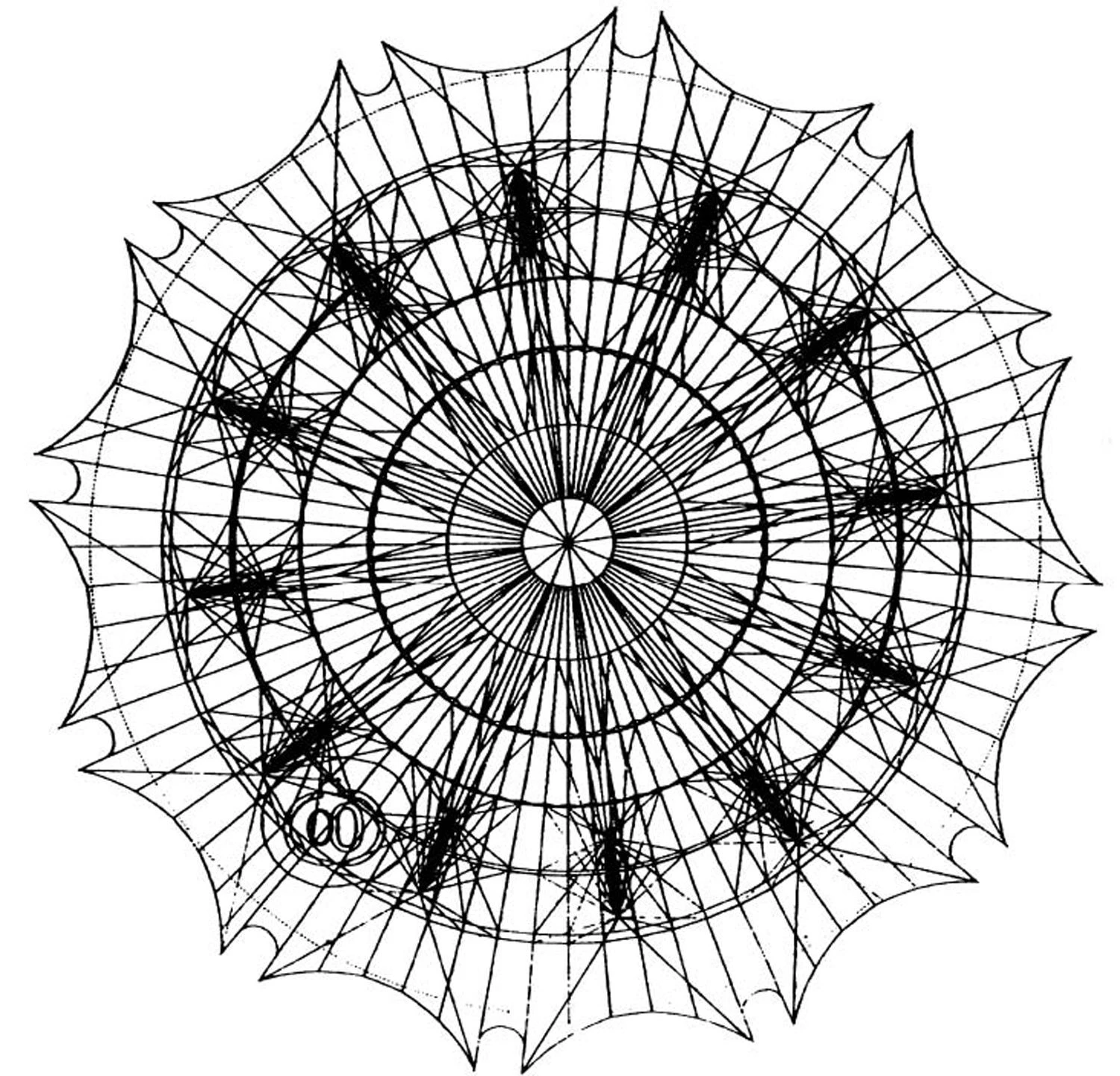

In the Spanish case, the perspectives of the huge new headquarters for the company Telefónica in the north of Madrid are not so much somber as uncertain. On a stretch of land larger than Retiro Park, the studio of Lamela has conceived an interminable serpent of glass whose 270,000 square meters of floor space will accommodate not only the main offices of the telecommunications firm but also a clinic, a sport center complete with an indoor swimming pool, three public auditoriums, and even a hotel – all in a warped geometry, and with futuristic details reminiscent of Flash Gordon that give the complex a techno-picturesque quality. This enormous project, which accentuates the city’s existing fracture into segregated fragments by transferring a large number of offices today inserted into the urban fabric to a specialized, peripheral precinct, contradictorily endeavors to crystallize in a single form an organization that is in a state of mutation, dividing and multiplying at the same time, while the waves of the stock market shake its upper echelons, making uncertain even the location of its main headquarters, currently in Madrid but perhaps tomorrow in Miami or São Paulo.

Warped geometries and futuristic details: the company Telefónica chooses the techno-picturesque for its new headquarters in Madrid, a never-ending glass snake drawn up by the Lamela studio.

For this international of the Dotcom and the world market, which has Aznar following the trail of Tony Blair or Al Gore in the same way that Villalonga seeks to emulate Bill Gates or Steve Case, the time has come to switch from website to content. Beyond technological mutations and the revolution of stock exchange expectations, the fusion of American Online and Time Warner has highlighted the question of contents, that is, which kind of information, culture or art is going to colonize the virtual field of the web and, in the long run, the symbolic universe of humanity. The matter goes further than the question of whether the planned merging of Terra and Telefónica Media would give a group representing already over a third of the Spanish stock market index the same dominant position in the realm of contents. When we contemplate a horizon that is more remote in time and more broad in space, the theme that emerges is the planetary homogenization of symbolic references and the inexorable trivialization of art and culture. And this is, without a doubt, one of the points of conflict that have put globalization and its discontents head on with one another in Seattle or Davos.

Without being apocalyptic, architecture and art should reflect on a digital future that does not reduce them to entertainment, that will not understand the environment as a mere stage set, and that offers alternatives to neurotic sensationalism. Again, what’s important is not so much if the recently started Sothebys.com or the established eBay.com have an edge over ceremonial auctions, or if in three years’time a virtual and all-year arco.com will have rendered the physical and once-yearly fair unnecessary. The essence is whether the web is going to be anything more than a voyeur’s tool for spying thousands of beds such as Tracey Emin’s, for reeling off the inexhaustible emptiness of chats, for contemplating the bottled life of all those contemporary Trumans who are the voluntary castaway survivors of the BBC or the shut away volunteers of Big Brother, the program of Dutch television that broadcasts live and non-stop the intimacy of a group locked away in a house. Because if the immaterial content of the media is to be a correlate of the material architecture of the New Economy’s priests, there will be no choice left but to take refuge in the near-silent movies of Aki Kaurismaki, in the dry abstraction of Pablo Palazuelo, in the rigorist and pòvero fundamentalism of the Danish Dogma, or, if push comes to shove, in the preindustrial or prehistoric nostalgia of John Zerzan, the ideologue of the Seattle revolt. And while the Telefónica bosses ponder about its future from the top of the Gran Vía head office, in the exhibition hall of the ground floor Francesc Torres puts, on the closed circuit of a baggage-claim belt, the severed head of a Zurbarán saint, which approaches us and again withdraws with the impassive movement of a star and the eternal multiplication of a vicious circle. Let’s not lose our heads.

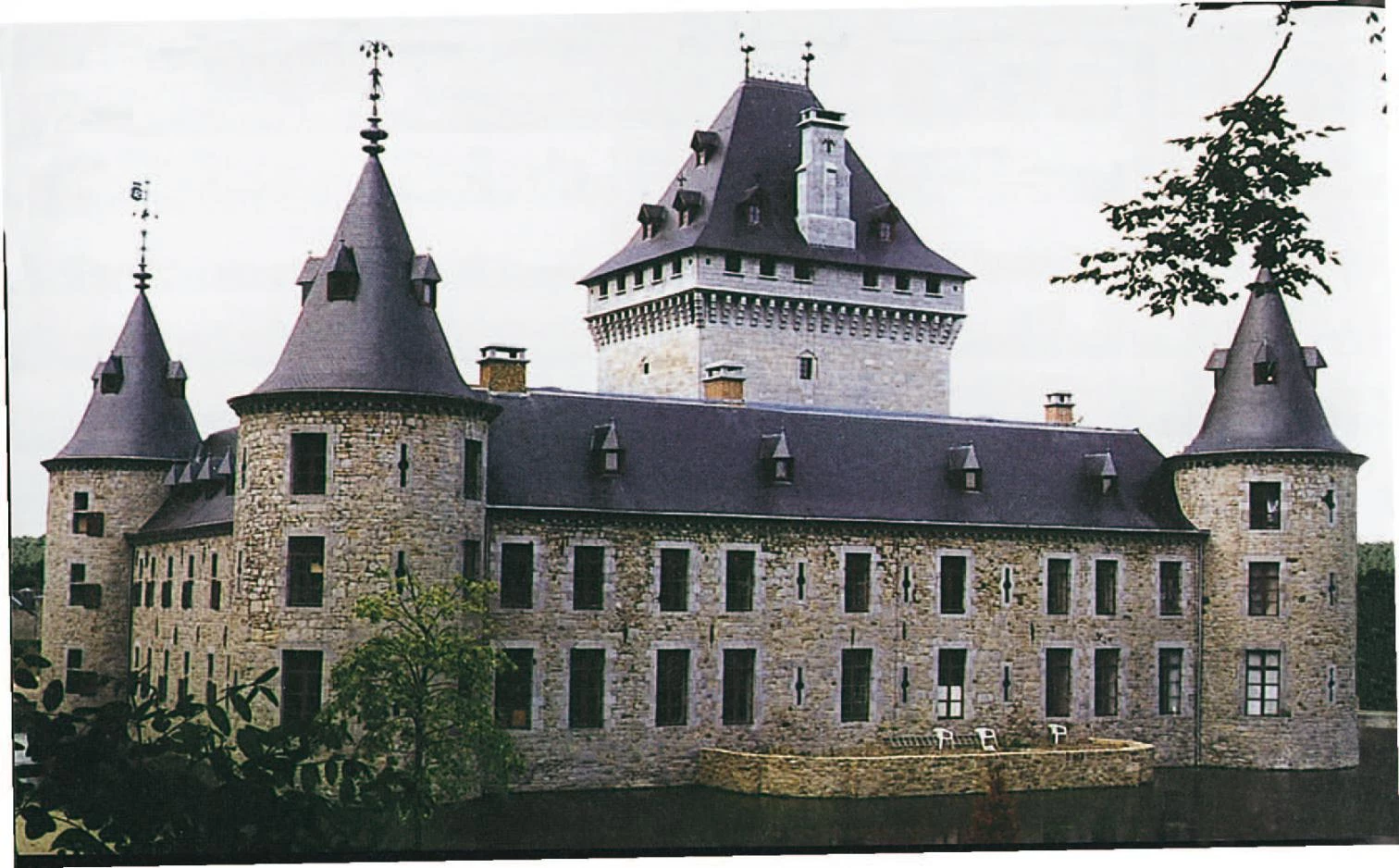

The virtual world of TV is extended with real architectures: in the Dutch Almere, site of the house of Big Brother, a replica of a Belgian castle will be raised to confer an identity on this anonymous town.

The Great Theater of the World

Daniela Tobar finally moved out of the transparent house of the Nautilus project with which the architects Arturo Torres and Jorge Christi have for weeks on end shaken Chilean society, more excited as it is about the publicity of the private than about the return of Pinochet. But it was not the airing of her daily life on television that made the actress leave, but the harassment of Peeping Toms crowding the security barriers. The experiment had made a paradoxical reality of that libertarian dream Agustín García Calvo expressed in his Business Letters of José Requejo, when he situated the true revolution in the public discussion of private matters and the private debate of public issues. Nevertheless it may have erred in superposing the literal transparency of modern tradition, with this Farnsworth House in downtown Santiago, on mediatic transparency of postmodern culture, where the panoptical showcase is equipped with cameras and screens. They might have learned something from the Dutch Big Brother, where the house permanently filmed by the mechanical see-all eyes of the producer Paul Roemer combined absolute transparency to the cameras transmitting images to internet and TV audiences, with extreme hermetism against the curiosity of oglers on the scene, surrounded by fences and wirings in the outskirts of Almere, a new city built as a domestic Utopia on a polder. The ultimate irony is that this placid community that likes to observe itself in the virtual space of the web should wish to celebrate its 25 years with a material construction meant to give it symbolic identity while serving as a venue for the weddings of young couples: a hotel and convention center reproducing as a facsimile the Belgian castle of Hargimont, incidentally owned by the real estate developer that supplies Almere with sweet homes and instant history...