Miracle in Santander

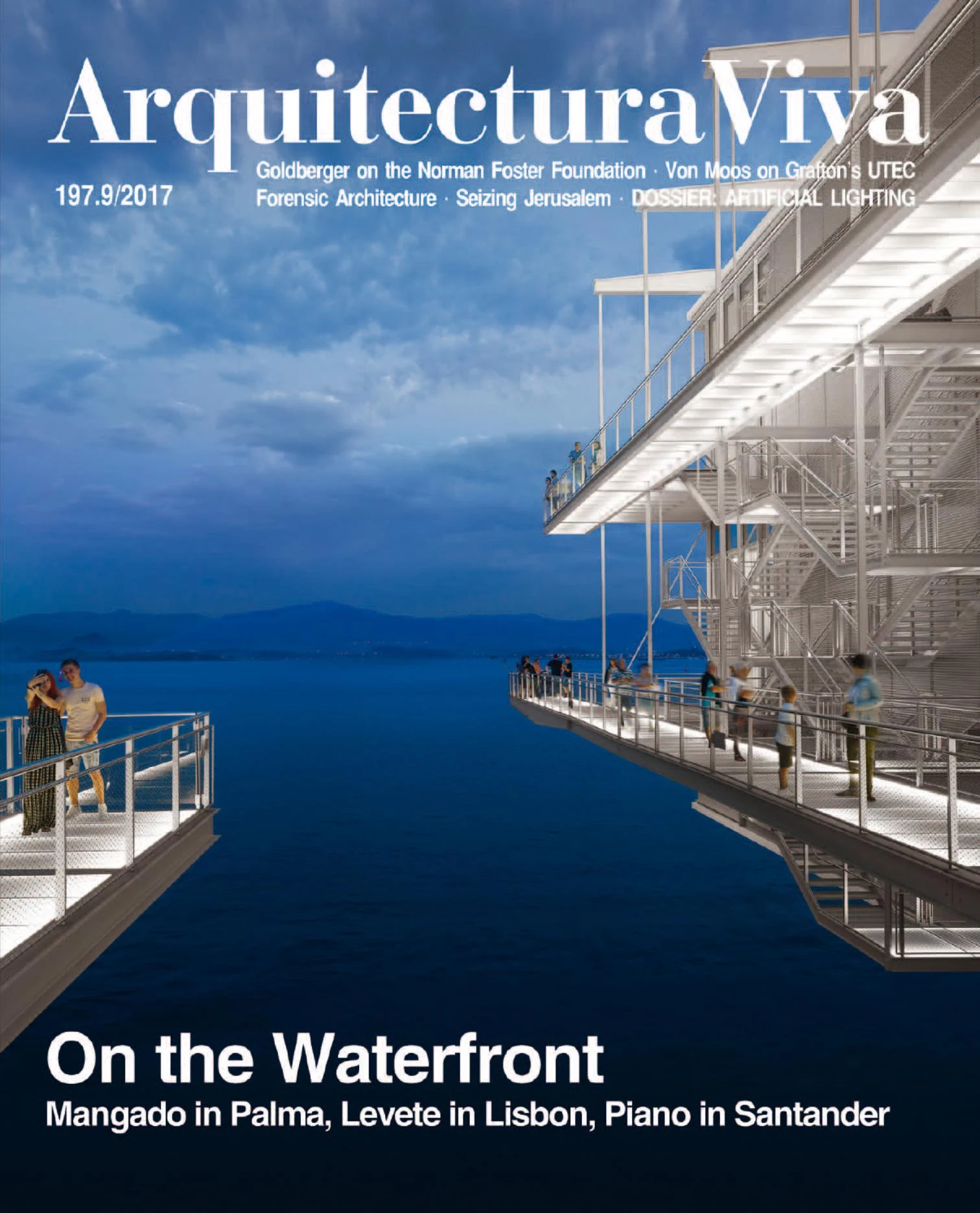

The meeting of a fisherman and a sailor has produced a miracle in Santander. Back in 2010, Emilio Botín, banker and fisherman, commissioned Renzo Piano, architect and sailor, to build an art center in Santander. Seven years later, the careening volumes of the Botín Centre rise on the edge of the bay, bringing to mind both a fish out of water and the hull of a ship, held up by pilotis that make them float weightlessly beside the dock they fly over. Indiscernible from the city because the pillars fuse with the trunks of the trees of the Pereda Gardens, which occupy the land between the street and the dock, and because the building is never taller than the magnolia, lime, and ash trees that form its vegetal vesti-bule, the center’s two lobes are joined with a series of stairs and platforms that form a large raised public plaza, framing extraordinary views of the bay.

Exactly twenty years ago, the inauguration of Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao was hailed by Herbert Muschamp in The New York Times Magazine with a categorical line: “The word is out that miracles still occur, and that a major one has happened here.” Two decades later the miracle is repeated a hundred kilometers west along the same Cantabrian coast, but this time starting from diametrically opposed premises; whereas the Guggenheim rose on the banks of the Nervión with colossal sculptural intentions that even made it appropriate La Salve Bridge, the Botín Centre seeks to go unnoticed from the city, hidden from view by trees and levitating at the dock so as not to block the passer-by’s vista of the bay: in contrast with the material miracle of the tempest of titanium, the immaterial miracle of the deference of disappearance.

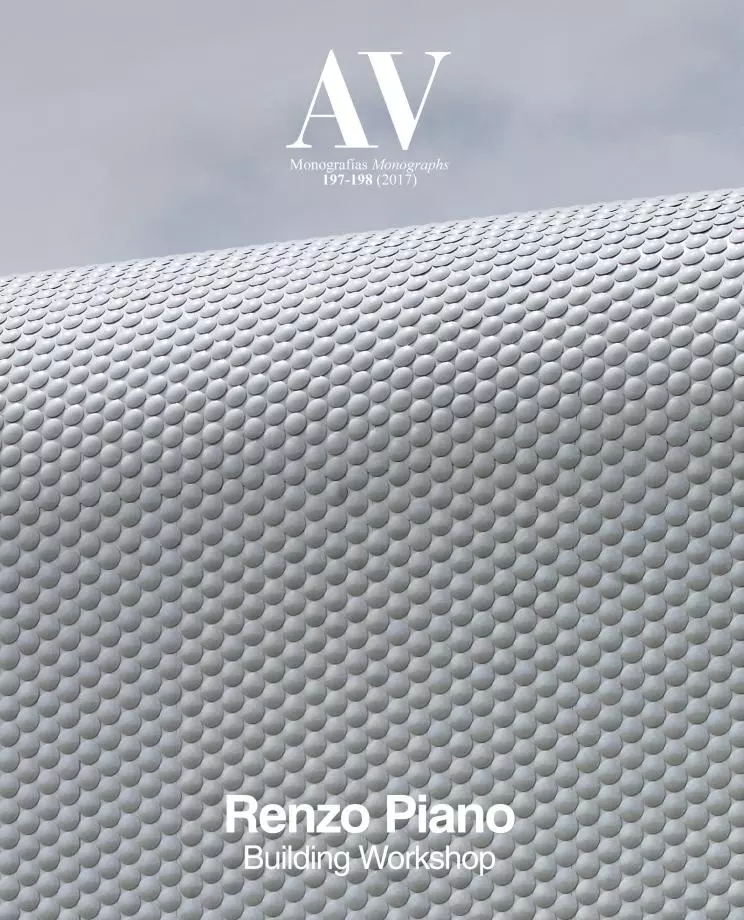

It is useful to compare the two because both use art as an instrument for urban regeneration and identity, and both sit on the water’s edge, extracting their warped forms from a fluid modeling that takes the city’s regular scheme into consideration but neither extends nor subordinates itself to it, as the first design for the Botín Centre did. That original project was sited across the historical headquarters of Banco Santander, and the final version in the definitive location, facing the market, has taken a formal autonomy that significantly improves on the intitial plan, proving once again the extent to which architecture, as public art, benefits from participatory design processes in which clients, government, and public opinion all play a part.

Formal autonomy does not always lead to sculptural projects, but it definitely creates conditions for the construction of memorable objects that can serve as icons in the communication mechanisms of a city or an institution. It happened with the Guggenheim and it will happen with the Botín Centre, which is already promoting itself with a characteristic foreshortened image from the dock, showing its emblematic profile but avoiding the architectural miracle of its fading when viewed from the Paseo de Pereda; and it also happened with another Cantabrian icon, Rafael Moneo’s Kursaal in San Sebastián, whose two slanting prisms hypnotically fix themselves to people’s memories.

Renzo Piano ha abierto en Santander su primer edificio en España, un icono evanescente que se suma a los que ya jalonan la costa cántabra.

Seen from the bay the Botín Centre undoubtedly has a characteristic silhouette, but its genius lies in its strategy of disappearance, in its elevation and break-up into two lobes – one to the east with the auditorium and the classrooms of the education center, and the other to the west with the exhibition halls, in addition to a glazed space at ground level containing the store and café – flanking the public platforms and stairs which, full of visitors, are the building’s social hub. If the Guggenheim gave Bilbao a titanic sea monster with scales of titanium, the Botín Centre explores the illusionist tricks of magicians who make their assistants vanish, and the bellies clad with discs of pearly ceramic serve above all to dilute the building in the horizontal light of the bay, giving all protagonism to the movement of people in this translucent metal scaffold they call ‘pachinko,’ maybe because people bounce between the lobes that border it like the ball in the Japanese pinball.

The Guggenheim is an affirmatively mas-culine work, imposing itself on the urban landscape whether or not there are visitors; in stark contrast, the Botín Centre – like its precedent in Piano’s oeuvre, the new Whitney Museum in New York, and perhaps also the future Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles – is completely amalgamated with the surroundings, drawing its energy and meaning from the random comings and goings of people: while the Guggenheim is from Mars, the Botín is from Venus, and if the Bilbao building managed to become an emblem of its time and transform architecture, perhaps the one in Santander will reflect current priorities and have an influence on contemporary practice, exhausted, as it is, by the turn-of-century proliferation of icons, and more in need of the luminous serenity that Renzo Piano’s work well expresses.

In Santander, the Botín Centre has grafted itself onto a city whose beauty as a resort tends to make it wary of novelty, without trying to impose itself on it: building a tunnel for the traffic next to the dock and expanding the Pereda Gardens – intelligently redone by the landscape designer Fernando Caruncho and lyrically complemented with a pond and four wells by the sculptor Cristina Iglesias – all the way to the water, so that far from being perceived as an obstacle, the new building allows penetrating its ceramic womb, climbing its glass flanks, and standing on its nautical roofs to enjoy the views and the breeze. Emphasizing this continuity, the park’s pavement of blue concrete reaches the dock’s edge, receiving light reflected by the water and the 280,000 mother-of-pearl ceramic discs which are the most characteristic feature of the work.

The center was inaugurated with a selection of artworks acquired over the last two decades and two monographic exhibitions: one on the artist Carsten Höller – well known for his evocations of amusement parks, such as the slide he installed in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall – which endeavored to offer a theme park ‘for the spirit,’ generously mounted on the upper floor, under a multilayered roof that regulates light through sheets of screen-printed glass and sensors, and opening on to the sea and the city at the far ends; and the one on Goya, with 83 drawings chosen out of some 500 preserved in the Prado Museum, which are a luxury for the eye and for the mind – despite the difficulties in displaying them properly in the first floor gallery – and which alone justify a trip to Santander. Two very different shows which reflect the breadth of interests of those running the center, or perhaps the absence of a clear direction in the institution’s future course.

Whatever the case, the Botín Centre – which is iconic from the sea and evanescent from the city, mechanical in the raised plaza and organic in the lobes, with fish scales and a ship’s hull – presents the same ambiguity, so the uncertainty of the contents vibrates in resonance with the indecision of the container, magical some days and miraculous on Thursdays.