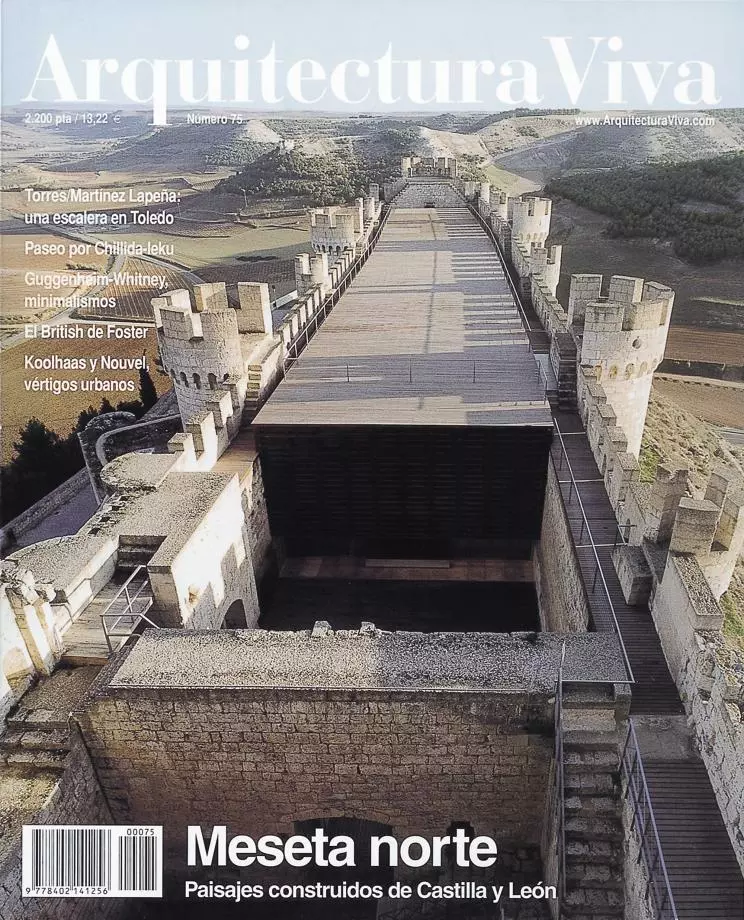

Castile is first an idea, and then a landscape. Being both a geographic and historic reality and a framework of the mind, the vast expansion of lands in the Douro region have dug out a symbolic niche in the collective imagination. Self-contained and outward bound, the mystical and bellicose identity that raised convents and castles was absorbed by a timeless Spain, opposing the monk-and-soldier to those in favor of locking the Cid’s tomb for good. But the medieval splendor of the cathedrals managed to blend for centuries with the flourishing wheat and wool markets to build a region of monuments, crops and cattle that would inspire the regenerationist creed of the group of ’98. In a desire to overcome the hesitant demography and severe climate which brought about the spirit of the moor, and as other European inland regions, Castilla y León strives today to converge with the new economic spaces shaped by the infrastructures and agricultural regulations of Brussels.

Though Madrid still exerts an influence upon the region, the latter does not depend on this today; nor does it rely on the presence of Castilian members in central government, as the prominence of Andalusia during the eighties was only in part due to the Sevillian background of the party leaders: it might be too evident to link Seville’s high-speed train to the socialist governments, that of Barcelona to the coalition pacts with Catalan nationalists or that of Valladolid to the current majority of conservatives. The future of Castilla y León today lies most likely in its cultural and physical resources, or as tagged by the European Union its endogenous potential, which another interior region, Aragón, sums up in the motto inner strength. Its heritage, natural environment, human resources and the language itself (named after Castile), are a few among many endowments which promise to safely guide this land of wine and bread from the agricultural to the post-industrial world.

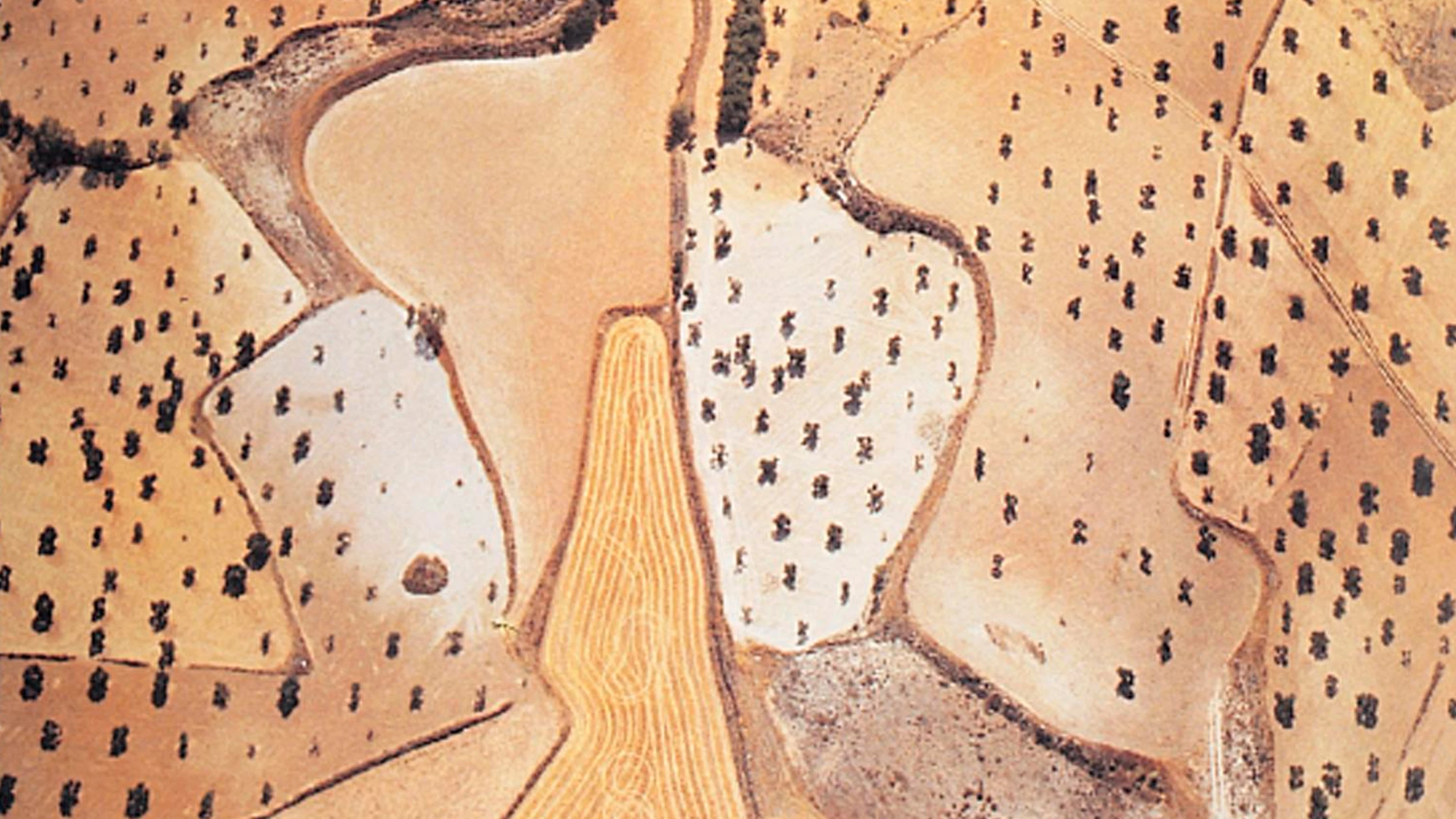

But this plateau is in fact a thousand plateaus, a region that vaunts both the largest number of cows and the second exporting company in Spain, drawing out a varied landscape that also sets distances: while Valladolid and Zamora are separated by a gap that cannot be measured in meters, they both partake of recent upscale architectural projects which show the effort put into redressing imbalances between two cities that stand at each end of the wealth index. To this effect, Castilla y León commissions its own architects, yet welcomes the talent of others, and many architects from the rest of Spain build in these persevering and sober grounds, from Burgos to León, and from Ávila or Segovia on to Palencia. It is to be expected from people who know themselves as belonging to the Valladolid of Delibes or the Zamora of García Calvo, but also to the Salamanca of the Basque Unamuno or the Soria of the Andalusian Machado. No other is the idea of this landscape.