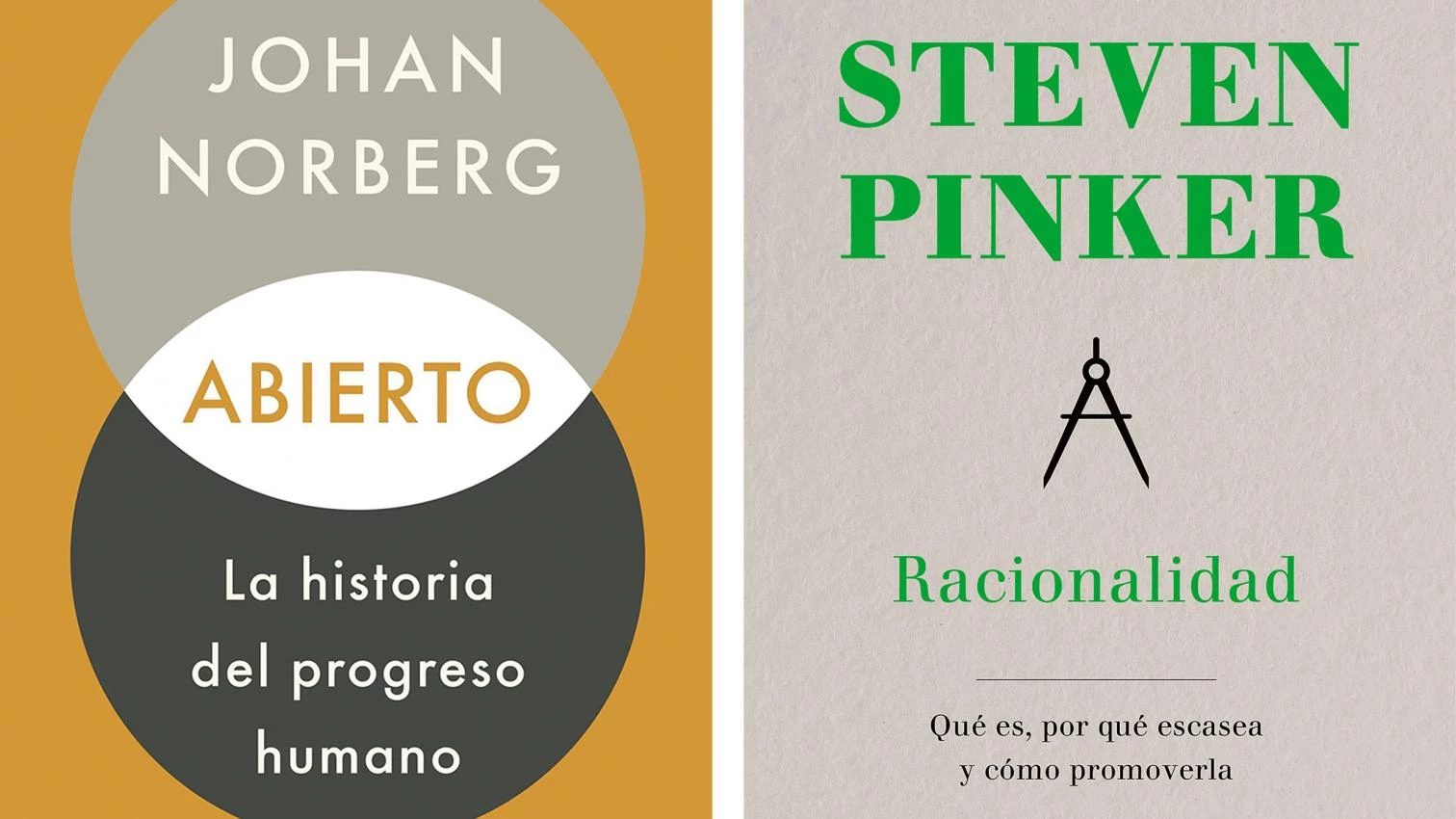

The Swedish historian Johan Norberg devotes a chapter of his new book to ‘open minds,’ and this is precisely what Steven Pinker, whom he so admires, advocates in his own latest work, a vibrant defense of rational thinking which the eminent Canadian psychologist presents with eloquent prose and scientific support. Both authors have been described as ‘new optimists,’ and surely this is why their previous publications, Progress and Enlightenment Now, were reviewed in 2018 under the title of a Rubén Darío poem, ‘The Optimist’s Greeting.’ Pinker, however, has stated: “their calling me an optimist only goes to show the extent to which journalists and intellectuals are incapable of understanding the concept of progress… which is something empirical, based on facts, and not a matter of whether you’re an optimist or a pessimist.”

In his defense of the Enlightenment, the popular Harvard professor indeed used a colossal deployment of graphics and data to demonstrate the world’s improvement through quantitative indexes; in his new volume, Rationality, Pinker instead avails of tools like logic, probability, or causality to stimulate critical thought and improve decision-making in both the private sphere and public life. Confused by the proliferation of conspiracy theories, fake news, and magical thinking that the pandemic has fueled, we entertain doubts about the rationality of our species, and the drift of politics, economics, and culture towards the realm of emotions only nourishes our suspicions all the more. In the face of such discouragement with civilization, Pinker upholds reason as the principal engine of material and moral progress, and from the angle of cognitive psychology he exposes the biases and fallacies that distort perceptions of reality, polluting individual behavior and adulterating the collective domain.

For his part, Norbert in Open explores the story of human progress, and does so by comparing societies that welcome exchange of goods and ideas with those which, by prioritizing property over cooperation, close themselves to commercial trade, intellectual traffic, and the circulation of people. With numerous examples covering everything from ancient Babylon or Greece to Covid-19 or the current geopolitical conflicts – and which in the case of Spain stretch from Roman times to bombs on trains in Madrid, passing through the caliphates, the Inquisition, or the voyages of Columbus, not to mention warm praise for the School of Salamanca, Francisco de Vitoria, Francisco Suárez, and Juan de Mariana – the book weaves economic history with the history of ideas in a persuasive presentation of the advantages of openness for personal wellbeing and social progress.

Pinker, frequently mentioned in the book, has lauded the clarity and elegance of his prose, no doubt sharing Norbert’s admiration for the John Stuart Mill who wrote: “In the case of any person whose judgment is really deserving of confidence, how has it become so? Because he has kept his mind open to criticism of his opinions and conduct.” That is the advice we get from these two social scientists, and I cannot resist closing this essay with a line by the Swedish historian which could well have been penned by the Canadian psychologist: “Our confirmation bias always traps us in a very limited view of the world, but free speech, peer review and cognitive dissonance set us free.

Johan Norberg: "Putin no lidera una superpotencia militar: sólo es un déspota con un botón nuclear"