Dead Seas

The Sea Museum of Vigo opened shortly before the sinking of the Prestige, whose oil spill caused an environmental disaster on the coast of Galicia.

The museum of the sea is the coast. In this thin and shifting line that separates two worlds and threads two ecosystems together, the sea manifests itself in its splendor and threat. No display is more emotive, and no exhibition more didactic, than the interminable fractal perimeter where the swimmer and the shipwrecked meet.The most gorgeous showcase and the most eloquent panel pale before the lyrical and rhetorical musculature of its foamy outline. Maybe this is why the Sea Museum of Aldo Rossi and César Portela colonizes the coast with distracted sheds that pretend to be almost involuntary, elemental forms of a vernacular naturalness that could well go unnoticed, assuming an elegant anonymity in extreme deference to that which is the real museum: the sea’s encounter with firm land. This sad and stormy December, Galicia exhibits its stained coastline like an elongated museum about the fragility of the technical universe, the vulnerability of the natural environment, and the impotence of our preventive systems. But this ominous black line is also entangled in scenarios of spontaneous invention, tumultuous determination, and convivial efforts that, with the sea as a backdrop, reveal the best side of our strange species, predatory and al-truistic at the same time.

Stained by oil, the coast of Galicia became an open air museum of our fragile environment.

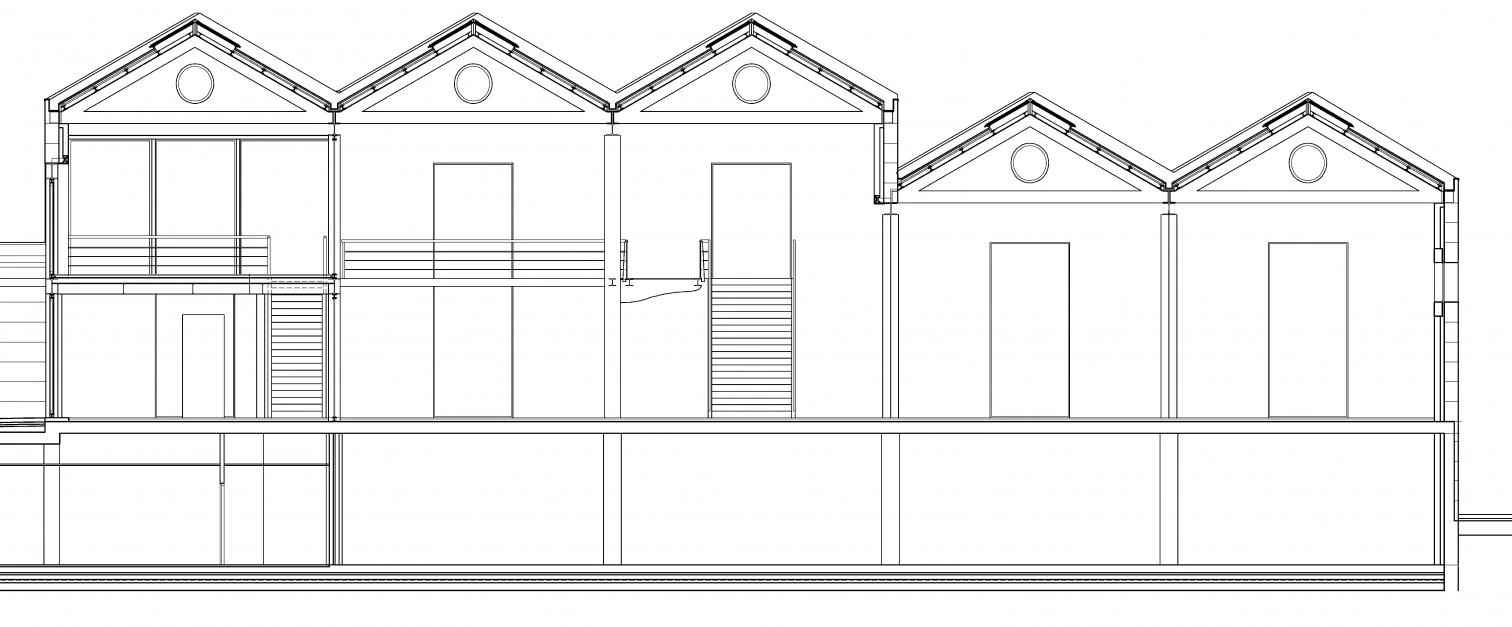

In its melancholic solitude, the Sea Museum presents a landscape outside of the realm of time that invites one to think beyond the current barrage of reproaches, offering its hermetic and archaic volumes as an emblem of stubborn persistence in the face of the fortuitous tempests of opinion. Amid the beautiful, exhausted choreography of volunteers in raincoats, the work of Rossi and Portela raises its stripped geometries to delimit a theater of memory, a metaphysical precinct of indifferent granite that resists the rough aggression of the sea just as the sea tolerates abrupt abuses and painstaking acts of repair. The industrial-like sheds of the museum –which incorporates the remains of an old canning factory –, the primeval house that accommodates the aquarium over the dock, and the toy-like light-house at the far end of the breakwater make up a sparse still life representing the sea with the lyrical, mythical violence of a fairy tale. Plagued by viscous spillage, the Galicians have every reason to be disheartened and angry, but the silent, primordial architecture of their marine museum is a hopeful symbol of the resistant tenacity of the elemental against the volatile storms of ephemeral history.

The premature death of Aldo Rossi impregnated this work with the perfume of an elegy. Heavily built on the edge of the water, it is the antithesis of his light floating theater, and its petrous aplomb expresses the solid certainty of inert matter, against the fluid, watery agitation of life around. A building of limits, solemn and severe, it sticks to the retina through innocent reiteration, like mollusks attach themselves to rocks, determined to survive in memory the way its masonry withstands time, and hides its timeless monumentality behind a casual conjunction of schematic pieces bordering on the picturesque in the coloristic cube of the seaside tavern. With this marine memorial, the architect who summed up his theoretical revolution in an enlightened cemetery left an abbreviated and deserted city that only oblivion will finally inhabit. In the end, it is the essential indifference of nature that gives the museum its desolate, tragic aura, while it is the min-eral impassivity of its geometry what freezes its forms in a still landscape.

A work by the late Aldo Rossi and César Portela, the Sea Museum in Vigo, on Galicia’s south coast, was built on the remains of an old canning factory, composing a timeless still life of elementary forms before the ocean.

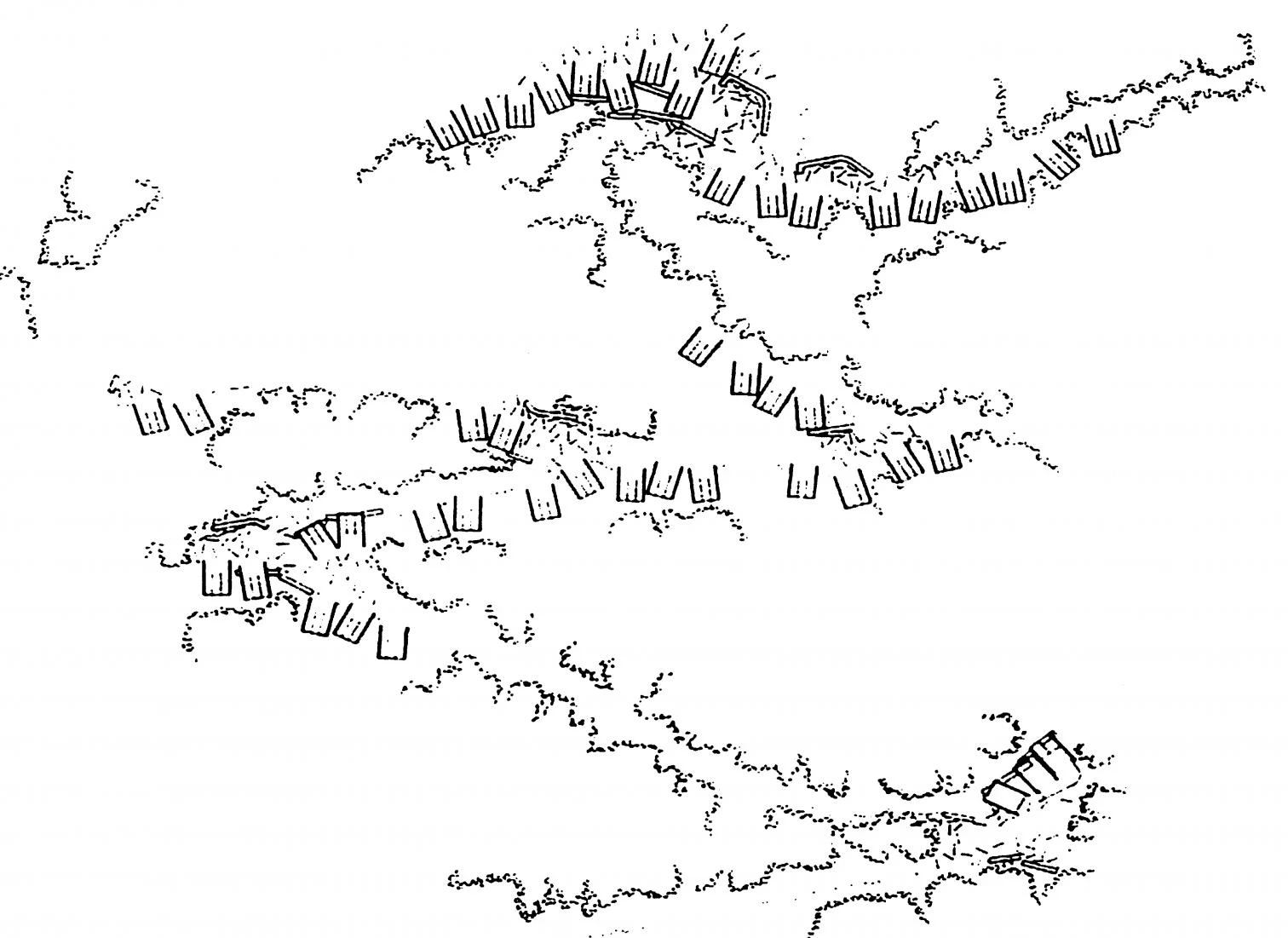

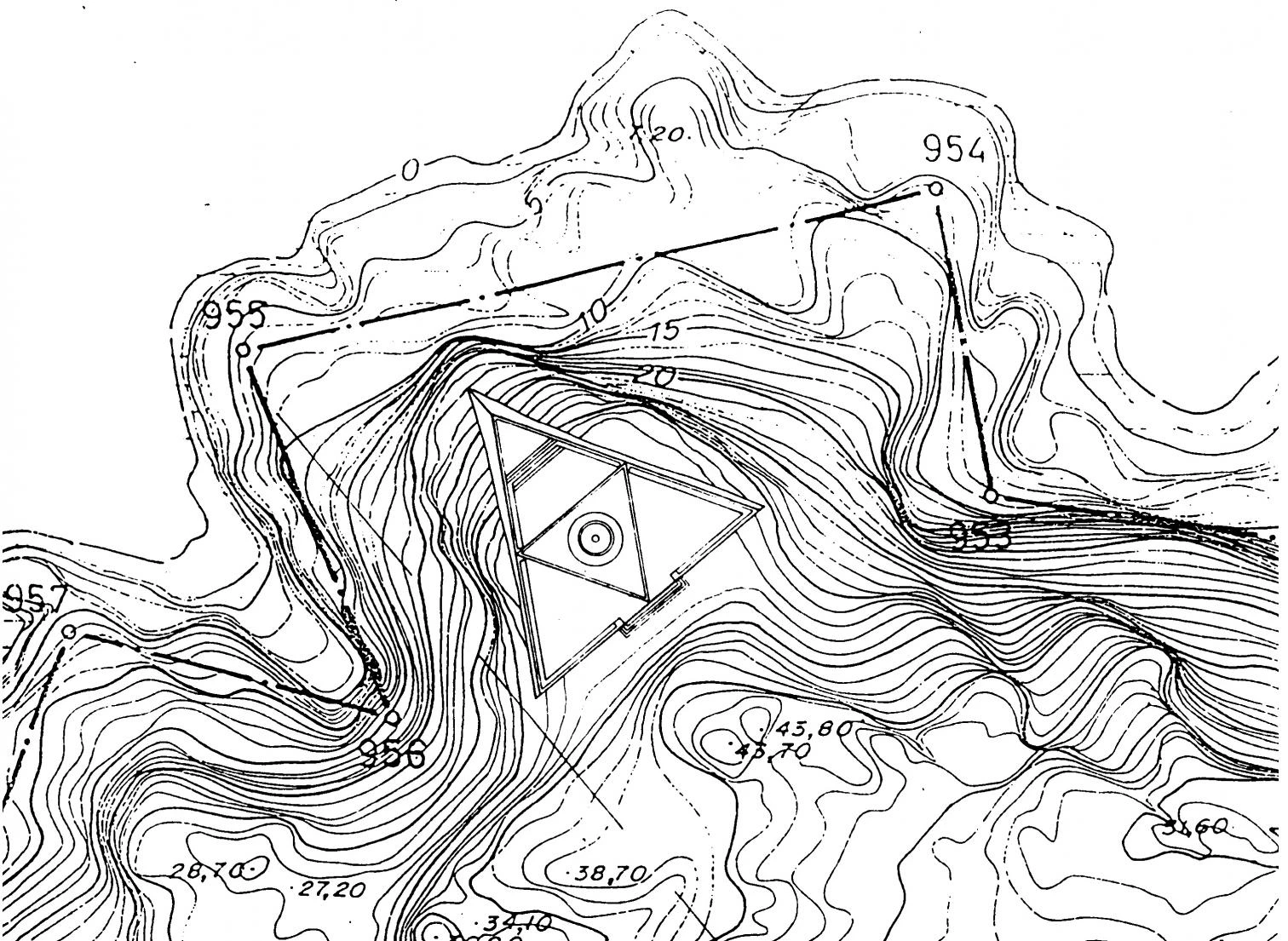

By a necessary chance, the Galician architect who brought this project to a conclusion executed two others along the stretch of the seashore most chastised by the black tide of the Prestige. If the Sea Museum rises in the calm interior of the estuary of Vigo, both the lighthouse of Punta Nariga and the cemetery of Fisterra are on exposed locations along the Death Coast, and these two works of César Portela are currently besieged by a dark and toxic paste that has given new meaning to the toponymy, turning the seaboard into an abject marine cemetery and the repetitive museum of a catastrophe. The Nariga lighthouse, built with Cyclopean stone blocks and granite ashlars, holds its lantern of steel and bronze atop the cylindrical shaft that rises from the triangular plinth, at once the prow and the bastion of a water- and wind-beaten promontory. And the Fisterra cemetery, laid out with cubes of granite on the edge of a path that descends to the sea, scatters the elemental geometry of the blocks of niches to shape an organic rueiro, decorating the finis terrae with a funerary garland..

Sooner constructions of consolation than archi-tectures of trauma, museum, lighthouse, and cemetery form a luminous and enlightened trilogy that deserves to be proposed as a sign of innocent reason against the guilty logic of the technical sphere. More a habit than an accident, the oil spilling is part of the foolish structure of economies industriously built on the compulsive consumption of fossil fuels, and this energy bulimia of the West is more responsible for the disaster than the plundering greed of corporations or the mean incompetence of politicians. Dead seas of petroleum are indispensable to a world of inequalities, as they are to military conflicts, mass tourism, or automobile-dependent suburban life. All of this was eruditely and eloquently explained by a radical humanist who died in Bremen early this month, near-forgotten as an inconvenient residue of the Utopian thought of the sixties. But Ivan Illich was a lucid and generous wise man who questioned the routinary certainties of a docile universe, and it is only the resigned conformity of these leaden times that has managed to bury with contempt the impassioned blade of his critical intelligence. Beneath the sand of Santander’s beach, that we once walked together, tar blobs can now be found, after the oil spill reached the Bay of Biscay. Cynics will think that under the paving stones was the beach, and under the beach the tar. But under that black paste are sand and water in motion, healing the wounds of the sea and stirring the dead work of a culture that disdains life.

On the Coast of Death, the stretch of Galicia’s coastline that was most damaged by the Prestige’s oil spill, are two other essential works by César Portela: in Punta Nariga, the end most exposed to the violence of storms,emerges the cyclopean shaft of the lighthouse; and by the cliffs of the cape of Fisterra, the stark granite cubes of a cemetery without walls lie scattered alongside a path that descends until it meets the sea.