Caveat pedes

A year after 9-11, both political tensions and cultural inertia paint a landscape that is hardly favorable to the pedestrians of history.

Pedestrians beware. During the summer, the state traffic authority carried out a campaign to remind pedestrians of their fragility. Independently of the rights that street regulations give them, pedestrians are the most vulnerable elements of traffic, and as such, must maximize precautions: “The first rule for the pedestrian is common sense.” Such realistic, skeptic caveat pedes serves to sum up this moment of the world: the pedestrians of history must be careful. Even when grouped in a multitude, the individual subjects seem as defenseless as the docile, naked bodies of Spencer Tunik’s photo-events, where the skin exposed to the elements is an emblem of our biological and social vulnerability..

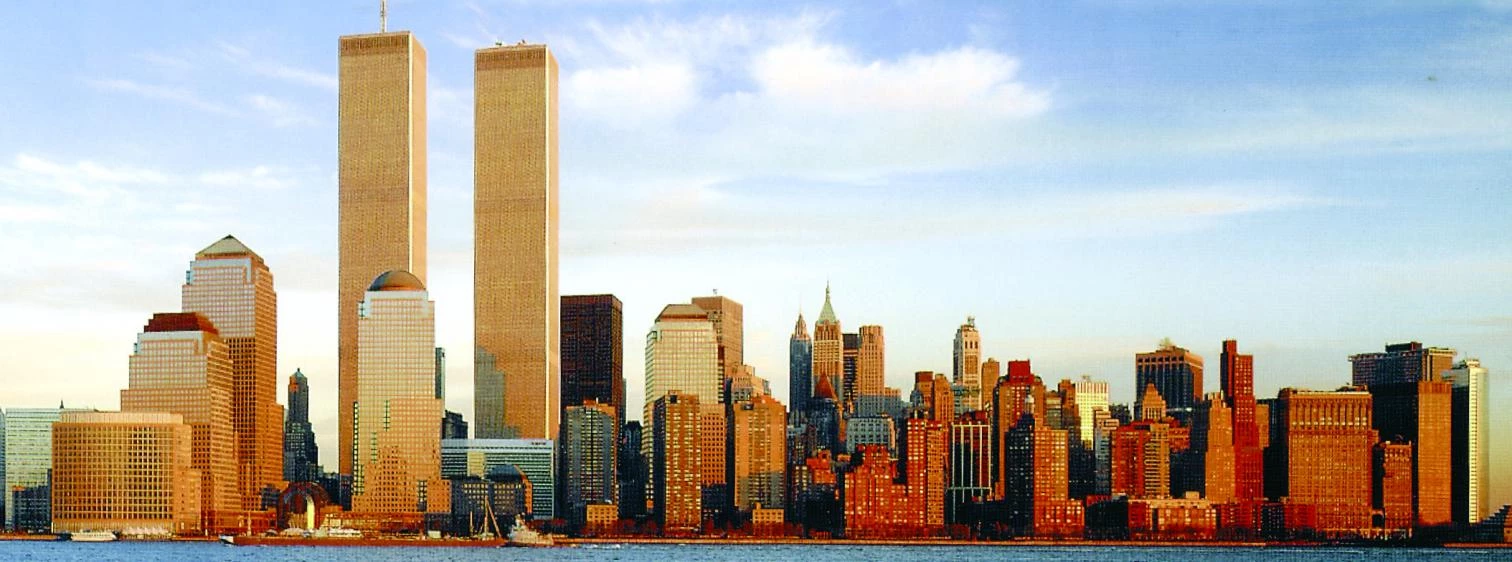

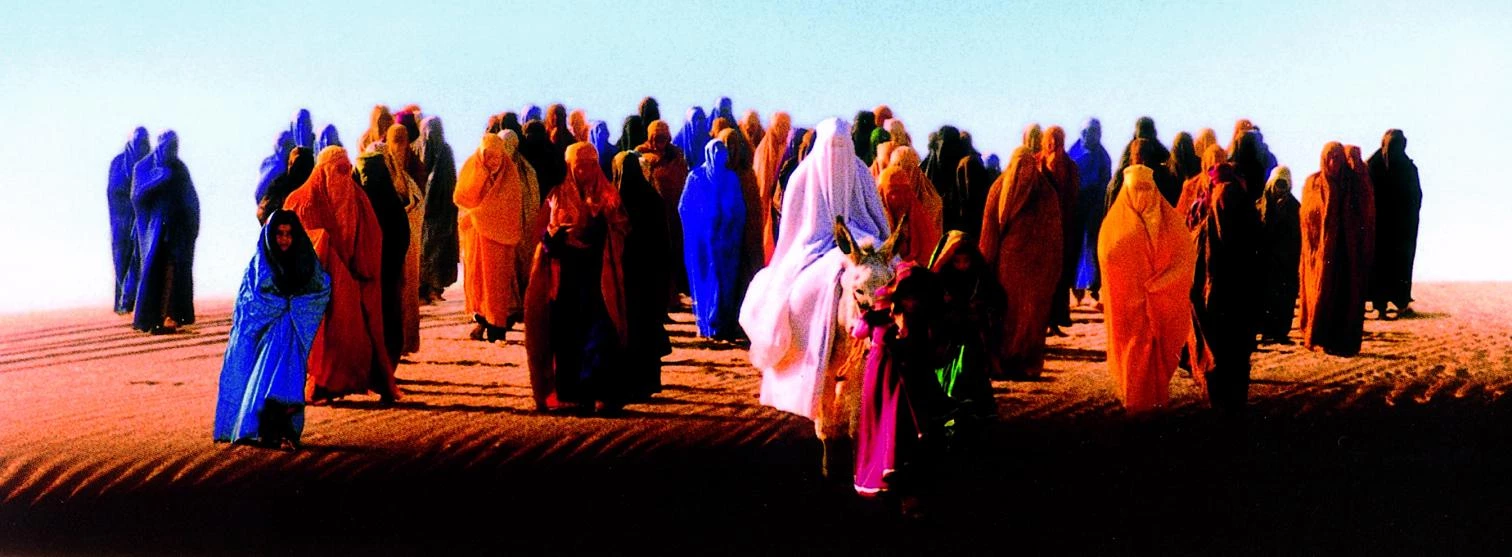

Arriba, imagen de Manhattan con las Torres Gemelas y fotograma de la película Kandahar.

Three centuries and a half after the Peace of Westphalia put an end to the religious wars by establishing an international political order, the only principle that governs us now is the right to pre-emptive intervention of an imperial power guided more by the specter of an ‘infinite justice’than by that of a ‘perpetual peace.’Nearly six decades after the Bretton Woods agreements, which set down the economic structures for reconstructing the landscape of ruins left by the Second World War, the institutions regulating capitalism reveal their hypocrisy or impotence before a system damaged to its very core of trust. And ten years after the Rio de Janeiro summit, hopefully presented as a turning point in the gradual wearing out of the planet, environmental and sanitary degradation advances with the relentless imperturbability that can be ascertained in the bleak turnout of Johannesburg.

The hungry child in Iraq, the ripped off saver in Argentina, and the HIV positive woman in Zambia are all pedestrians run over by the political, economic, and epidemiologi-cal catastrophes of a world in crisis: not so much collateral damage of recomposition, but necessary victims of decomposition. A year after 9-11, the flood of solidarity and emotion provoked by the attacks has vanished like a cathedral of smoke, and Europeans feel the Atlantic Ocean to have widened; but Europe’s expressions of reticence toward the empire are justdiscreetfrowns of an old societythat knows itself to be an incubator of totalitarian ideas and regimes. Like the Italian communists of the compromesso storico, who joked about the glorious path that had led them to be with Gramsci against Mussolini, with Togliatti against De Gasperi, and with Moro against Fanfani, the European intellectuals who were with Lenin against the Tsars and with Mao against the Mandarins are now with Colin Powell against Dick Cheney. Such is the definition of maturity in our times..

Europeans and Americans are accomplices in building a system that centrifuges poverty to the peripheries, accentuating material, educational, and sanitary inequalities. Europe’s Common Agricultural Policy and the USA’s Farm Bill together strangle the rural societies of the Third World, generating as many migratory flows as torrents of resentment. A year ago, The Other was the Muslim, sequestered by religious fundamentalism as a result of the failure of its society in secular modernization, and where only cynicism rescued the Saudi oil princes from their protagonism in the ‘axis of evil’. Today, The Other is the poor, primitive, deformed, subhuman slave who rises up – deceived, ignorant, and meek – at the expropriation of his insular universe, patera and plantation fodder that frontiers filter with ever decreasing efficiency. The threat of the Taliban has turned into fear of Caliban.

The trauma of September 11 engraved a schematic interrogation in the western conscience: why do they hate us? But the elemental violence of the question contains a message that has not been received. The cultural mood in the empire oscillates between the celebration of the uniformed heroes, a sentimental vein in which the leftist intelligentsia has sought refuge, headed by the Tim Robbinses and Susan Sarandons who pay tribute to firemen in The Guys; the optimistic and elegiac patriotism of the Bruce Springsteen of The Rising; and the country, irascible, aggressive chauvinism of Toby Keith, who has brought his xenophobe hymns – produced by Spielberg’s Dreamworks – to the top of record sales lists. The awareness of vulnerability created by 9-11 has perhaps promoted solidarity, sex, or alcohol, but it has not brought about the soul-searching that critics like Noam Chomsky have called for from the margins of the system. Perhaps, as Paul Krugman predicted on the occasion of the Enron fraud, only financial scandals will have in the end the capacity to shake the smug indulgence of the United States, a deaf giant that still refuses to accept the fact that the world is governed as much by arms as through reputation.

In its subsidiary modesty, architecture still offers few signs of that change of mind that many anticipate or desire. The problem of rebuilding Ground Zero, which could have constituted a formidable laboratory of ideas, soon caused a split between the theoretical and oneiric proposals of the fifty odd architects summoned by Max Protetch Gallery for an exhibition that, after stints in NewYork and Washington, travelled to the Venice Biennale, and the six pragmatic real-estate projects that were subjected for public approval and finally put aside by the developer. The artistic statements of the exhibition showed ideas without deeds: reputation without arms; whereas the techni-cal proposals of the developer revealed deeds without ideas: arms without reputation. Will these two worlds ever meet?

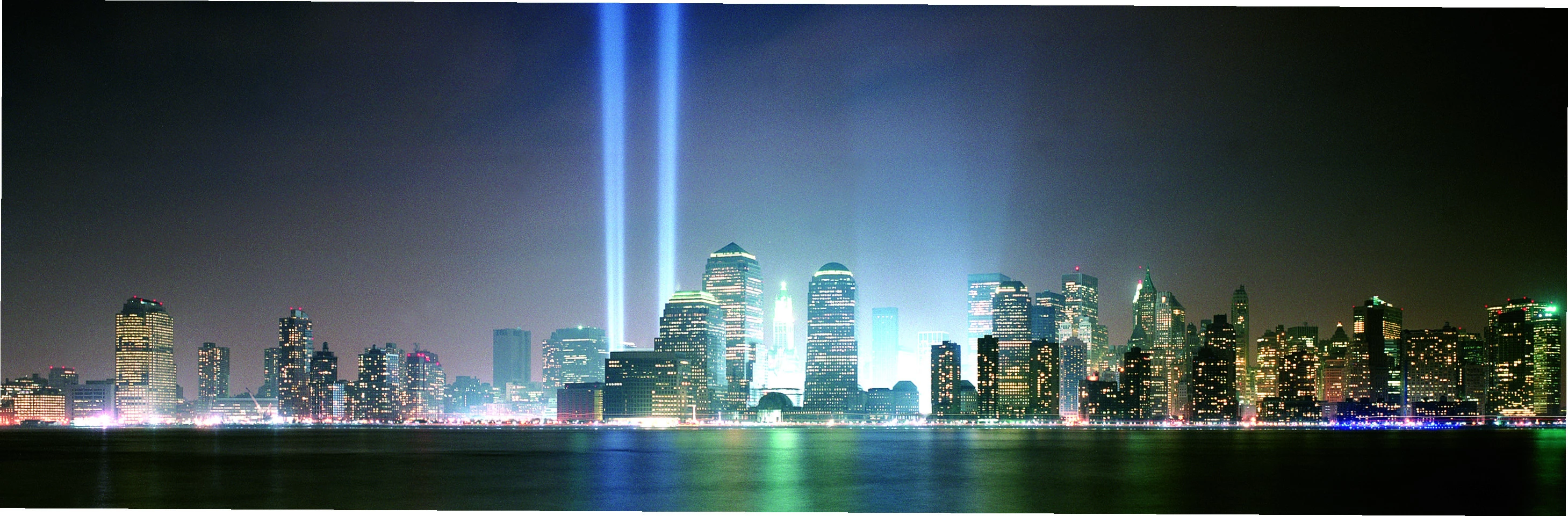

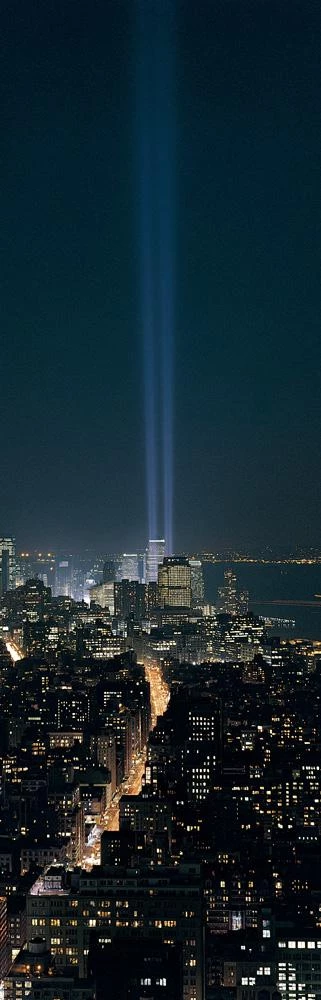

Six months after the destruction of the two skyscrapers of the World Trade Center, New York evoked its lost profile with two ghostly towers of light that went up from an empty plot near Ground Zero.

In any case, the contemporary malaise of architecture and its dilemmas lie in areas out-side that of repairing American pride or re-building the urban fabric of Manhattan. If the voids of America Deserta served to illustrate Gertrude Stein’s “There is no there there,” the congested hollow of Ground Zero is a perverse materialization of Mallarmé’s “rien n’aura eulieu que le lieu”: an ontological lyric that sticks like a symbolic skin to a place that struggles to free itself of its ominous temporality, and which the most vacuous rhetoric – from the Towers of Light proposed by artists and architects to Salman Rushdie’s suggestion of a replica crowned by luminous atriums – imagines as poor imitations of ghostly presences; but a metaphysical poetic that also verges on the prosaic corruption of construction by spectacle and duration by event. The phrenologists looked for the spirit in the bone, and Hegel used this naive materialism to stress that there is no subject without resistent and inert matter: the spirit of architecture also inhabits the bone, a stubborn material that molds ideas with forms, and vanishes in the thin air of phantom images.

The discontents of architecture have inevitably perceived 9-11 as a terrifying event of Heideggerian filiation, a decisive strike on technology and Americanism at their spiritual and material heart. But to the extent that the republic has become an empire and the respublic is now the res-total, the challenge on globalization is not a challenge on modern totalitarianism, but on the totality of civilization. Beyond the limits of the empire, there are only barbarians, Calibans to be repressed or exterminated altogether. At the current cross-roads, the path that leads from Washington to Baghdad fades in the elusive mirage of Iraq’s ‘weapons of mass destruction’ – a kind of Hitchcock’s MacGuffin in the media narration of the crisis, as Slavoj Zizek describes them –but the imperial unilateralism leaves little room for doubting the impending catastrophe. “Erich Auerbach once wrote” – Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri remind us – “that tragedy is the only genre that can rightly be called re-alism in western literature, and this may be true on account of the tragedy that western modernity unleashed in the world.” It could well happen that this time we are living as a dawn is really a dusk. But the indecisive light can only be a warning for the pedestrians of architecture and history to intensify caution.