Machine and monument

Industrial Heritage: Past and Future

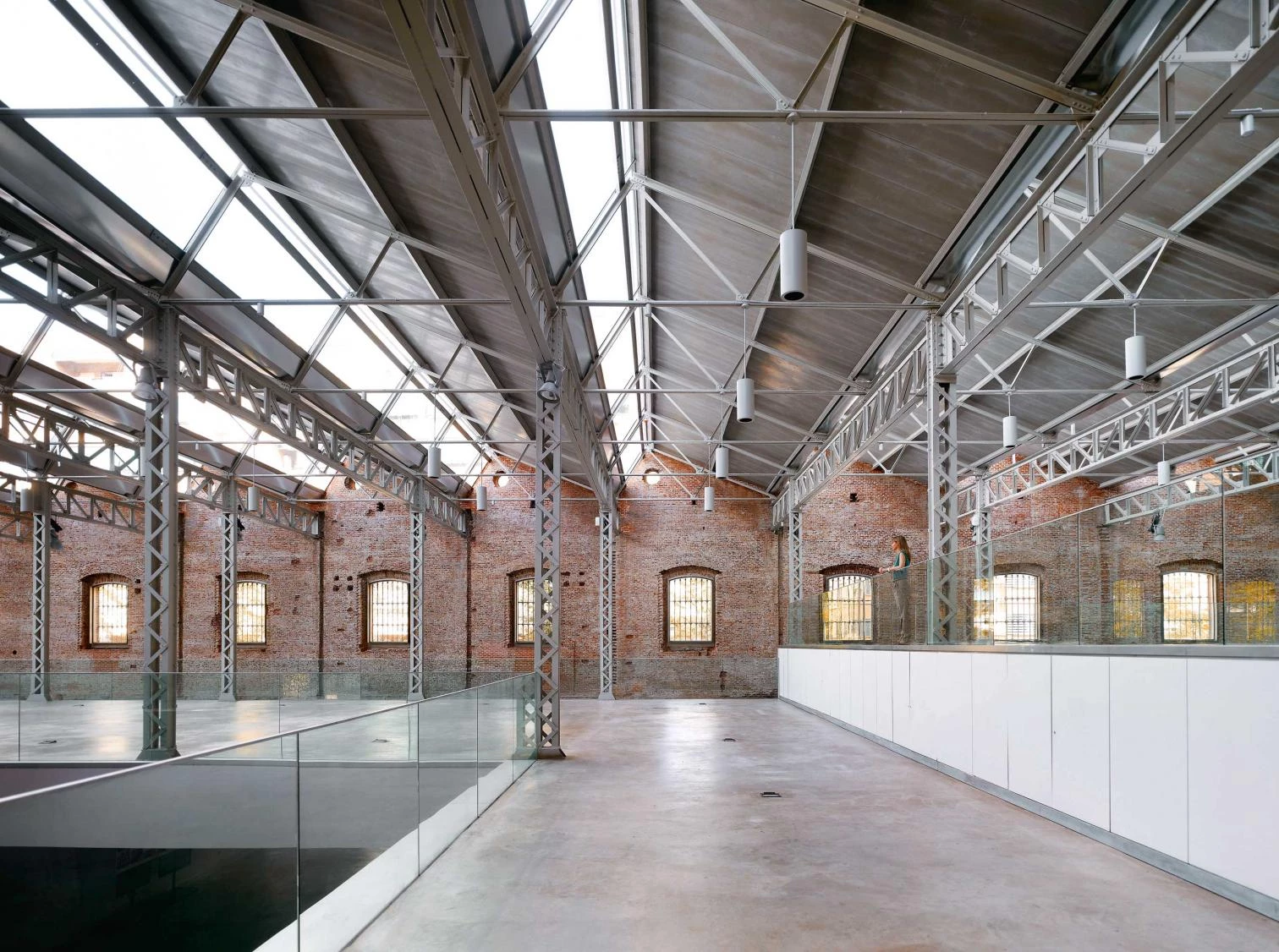

Ensamble Studio, Reader's House, Madrid

Modernity has had a curious destiny: to devour itself like the god Saturn his offspring. Conceived as demands of a present that wanted to be the future, the modern tenets have suffered the passage of time like few things are able to do, to such a degree that what just a hundred years ago was futurist utopia is today almost archaeological material, or at least heritage material. Modernity is by now very old, and its products, which once were upheld as manifestos, are nowadays classified, protected, virtually armor-plated, to save them from the devouring teeth of contemporary life, what the modern architects said were messengers.

This transformation is affecting iconic houses, offices, cultural buildings, but also constructions of the kind whose conversion into heritage pieces is particularly complex: industrial facilities, aged factories. Complex, first, because it is difficult to change the use of structures originally intended to serve highly specific purposes and thus equipped with highly specific systems. Complex, too, on account of their scale and form, so different from conventional buildings, forcing architects to rethink many presuppositions. Complex, third, owing to their aesthetic, traditionally held in disdain and with a technological tone that can be hard to reconcile with the stylistic aspirations of designers and the tastes of the public. And complex, finally, due to what they represent, because industrial premises, factories, are so impregnated with symbolism and even ideology – since the 19th century they have been seen as emblems of modernity and progress – that any intervention on this kind of heritage involves a reprogramming not only of uses, but also of values.

Notwithstanding, in Europe, America, and Asia, old manufacturing facilities have for several decades now been giving architects new work opportunities, and at best given rise to extraordinary projects in which the development of mixed programs and the combination of languages have contributed to reviving entire zones of cities that were much degraded not too long ago, and to building a new awareness of heritage, broader but also more flexible, more contemporary.

This dossier of Arquitectura Viva gives a picture of the challenge of working on industrial heritage through three Spanish examples that have involved a radical change of use. First, an engine factory on the street Méndez Álvaro (Madrid), dated 1905, transformed by Foster+Partners into offices for the Acciona Ombú Campus. Second, a brick warehouse in Santander, from 1908, converted by Fernández-Abascal+Muruzábal and GFA2 into headquarters for the Enaire Foundation. And to close, a lock manufacturing plant in Mondragón (Basque Country), from 1939, refurbished by Jovino Martínez Sierra to stand as Kulturola Building.

Rafael de La-Hoz, Daoiz and Velarde Cultural Center, Madrid