Latapie House, 1991-1993, Floriac-Bordeaux (France)

There are moments when it feels like we are at a turning point. Moments in which the insight and ingenuity of certain architects, their perseverance, the determination of a few builders, and certain changes in the collective imagination open up other perspectives, transcending common sense, inconceivable some years ago. Especially in the case of housing.

It happened in France with the Unité d’habitation in Marseilles and its three avatars, and at the same time – though one might think otherwise – with major social housing developments. And later, too, with the rise of urbanism and the topographic, terraced Renaudie residences in Ivry or Givors. With these references, generations of architects offered new visions, building utopias, but concrete ones. The inhabitants followed them, some with hopes for a new life, others less convinced. And so life and its vicissitudes entered the buildings: a succession of families, a diversity of people, a heterogeneous and cosmopolitan, albeit often reticent world. But other preoccupations cropped up over the years, public policies changed course, and old commitments were forgotten. We were moving on to something else.

These are times of frugality. Lacaton & Vassal mark a new rupture. Their work is comparable to what Rem Koolhaas did on ‘what we used to call the city,’ and junkspace: a summons to free ourselves of dogmas, of convenient ideologies never questioned, blind to contemporary realities. An invitation to realism.

These revolutions are true paradigm shifts. They affect our conception of everyday life, customs, habits, comfort, and good taste. They also affect what we do with materials, their supposed fineness or crudeness, their installation on the site, and their aesthetics. We are talking about the epistemological ruptures that Bachelard described in La formation de l’esprit scientifique. Prejudices, common notions, are ‘obstacles’; one day they will disappear, and new ideas will take their place. Bachelard thought in terms of progress because science progresses (he referred to them as an ‘ensemble of rectified errors’). Architecture, in turn, does not progress. It advances in rough starts, with a certain propensity for amnesia, even denial.

Although they have not produced any canonical texts, settling for interviews published in the press, Lacaton & Vassal have come up with a veritable doctrine of contemporary architecture. A doctrine built gradually. Without lyricism, without literature, far from pretensions to stardom. A doctrine devised with few ingredients, and with the same dedication, constancy, and good sense of an artisan. Not to mention the exemplary nature of their works, which show a new kind of beauty, graphic rigor, and luminosity, with pearly surfaces, reflecting glass panes, and silvery gray curtains; with undulating metal sheets and polycarbonate panels; and especially with the light and crystalline atmosphere found in photographs of their interiors.

They represent a new current in the French scene, embodying a kind of national school that mixes rationalism, ethical and political responsibility, attention to social issues, and frugality. They could be included in the group NP2F, members of which were among their collaborators: Christophe Hutin, in charge of the French pavilion in the next Venice Biennale; the firm Bruther, author of a transparent small tower dedicated to innovation on the peninsula of Caen and a residence in the Cité universitaire of Paris; or Studio Muoto, comprising two old collaborators of Perrault to whom we owe a sports and restaurant complex on the Saclay campus, with volumes superposed and interlinked in a highly sophisticated way.

Buildings for Living

To get more space and more light for the same cost. To not destroy in vain, but preserve what can be. To make the most of the beauty or mere existence of the things they find. To let people furnish and decorate their homes as they wish, allowing for disorder. Their worlds, their intimate corners, their private poetries, their sorrows. To give inhabitants their freedom instead of working against them. To propose spaces that are as little defined as possible. Not functional, but flexible. This is far from the authoritarianism of the modern architects, of the Le Corbusier who denounced the ‘poor women’ in the French Salvation Army’s Cité de Refuge claiming to be drowning behind its hermetic facades, urged the Communist Party to impose the ‘necessary discipline’ on ‘its people,’ and complained to Minister Malraux about a ‘sort of conspiracy’ that the occupants of the Cité radieuse of Marseilles were plotting against his innovations. Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal visit the dwellings they build or refurbish in order to see how the people live, how they organize, fix up, and appropriate the spaces. And they leave satisfied. The diversity of all those lives enlivens the most monotonous facades with infinite variations.

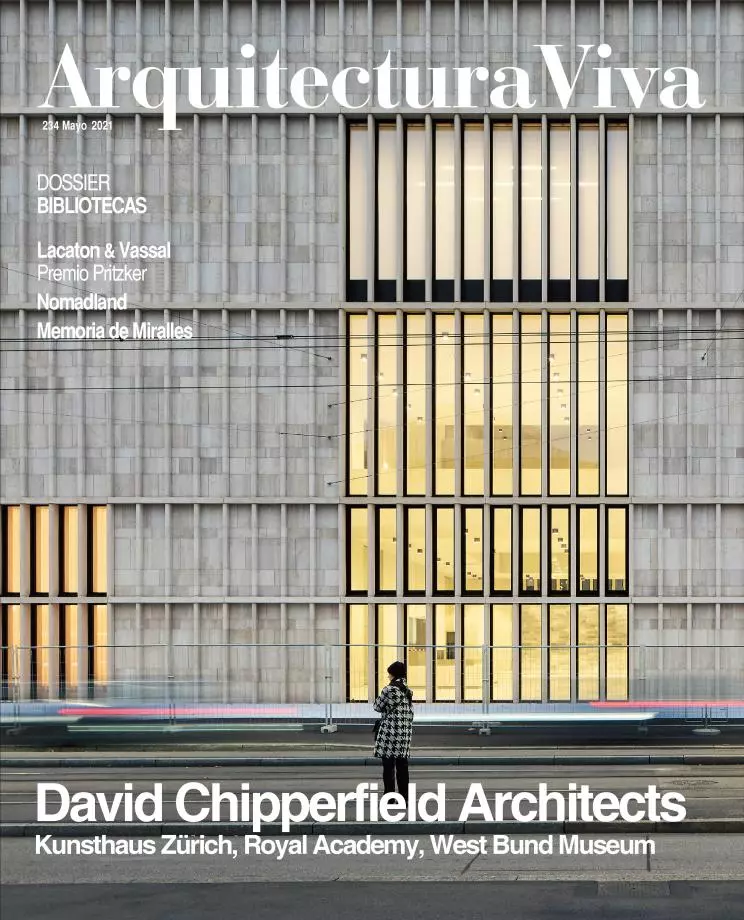

What’s surprising about the attitude of these architects is their insistence on staying on the same path that they started off from with the famous Maison Latapie Floirac, thirty years ago. In his Essai of 1753, the abbé Laugier traced architecture back to the “little rustic cabin made of fallen branches in the forest”: a “kind of roof he covers with leaves set closely together so that neither sun nor rain can penetrate.” Le Corbusier dated his work back to the Maison Dom-Ino of 1914, a simple frame of piles and slabs of reinforced concrete, a “pure and total conception of a whole system of building,” a technique that enabled him to “manifest a new sentiment of architectural aesthetics.” Lacaton & Vassal go back to a hut they built in Niamey in 1984. It is their Adam’s house in Paradise, their rustic cabin, in which, without a doubt, they went by the words of the abbé: “It is in coming near in the execution of the simplicity of this first model, that we avoid all essential defects, that we lay hold on true perfection.”

Straw hut, Niamey, Niger (1984)

There have been those who have wondered if buildings inspired by horticultural conservatories were at risk of “backing cheap architecture” and even “contributing to generalization.” If enlarging buildings by means of winter gardens or greenhouses – as in the Bois-le-Prêtre tower renovations and the 530 dwellings of the Grand Parc in Bordeaux – or intermediate spaces – as in the architecture school of Nantes – did little more than increase shade in interiors. Doubts have been cast on the real usefulness of flexible, functionally neutral spaces, which are dismissed as generic, devoid of qualities, and lacking in contrast.

One could worry about the aging of materials, about the moment when lightness becomes fragility or poor quality. Especially when there is no more place for certain contemporary social models, such as the loft trend, grunge aesthetics, the bitumen floors, warehouses, and DIY store that are so accepted nowadays. And when for the residents or users the pleasure of having been pioneers in these ascetic architectures and these structures of galvanized steel assembled with monkey wrenches have lost all meaning. Or the day they find themselves weighed down by social difficulties.

School of Architecture, Nantes, France (2003-2008)

In the apartments designed by Lacaton & Vassal, whether new or revamped, the thing is to live, and especially to be free to live in a cosmopolitan world. This may be with designer, petit bourgeois, or Maghrebi furniture, new or recycled; and in rooms bare or cluttered, with flowers, rusty bicycles, or storage boxes piling up in the balcony-sunrooms. It’s all about living. Living freely. It would be interesting to find critique, literature, photography, and documentary films that explored these operations for us. A bit the way things were done before, when, forty years ago, François Hers and Sophie Ristelhueber took pictures of low-income housing interiors in Wallonia. The former in color, no occupants in view, in snapshots brightened up by flash, with landscape-framing windows looking like paintings on the wall; the latter in black and white, with images exuding an aura of reclusion and desolation.

Almost as in a sociological study, the apartments could be visited at different times, even on a rainy day. This would give more insight on the utility of Lacaton & Vassal’s formidable effort to break standards, preconceptions, and norms, for which they have merited the Pritzker Prize. It would also add shade, chiaroscuro, and nuance to all that light they promise.

And to return to Le Corbusier and go full circle, let me quote something the writer Jean Paulhan penned at the end of a trip to Switzerland that he did in April 1946 in the company of Dubuffet and the architect, who had gone on and on about his theories. “An architect,” he wrote, “known for building happy houses, crossed by air and sun.” Houses where for his liking, “all that’s wanting is a small, dark, reflective room.”

Transformation of 530 social housing units at Grand Parc, Bordeaux, France (2011-2016)