Here Comes the Cold

The Great Recession froze the economy of the planet, ending with iconic works a decade that witnessed the bursting of one real estate bubble after another.

The planet heats up, the economy freezes, and a tremor of uncertainty shakes our lives. A rosary of crises has woven a net of pessimism that holds the signs of recovery in its mesh. After the market panic of 2008, the year 2009 has experienced a boom that paid no attention to trade unbalance and monetary risk, and a dynamism in some emerging economies that is not incompatible with the weakening of the global governance, unable to deal with thedilemmas of climate and terror.

Spain suffered the paralysis of the cranes that fed its real estate boom, while the olympic China saw how the just topped CCTV complex went up in flames in Beijing.

In architecture, the completion of the last crop of emblematic works has taken place at the same time as the collapse of numerous real-estate bubbles, a paradoxical coincidence that is exemplified well by the simultaneous opening of the Burj Dubai – now called the Burj Khalifa, whose 818 meters make it the world’s tallest building – and the crumbling of the Emirate's finances, rescued from bankruptcy by its neighbor Abu Dhabi, whose oil-driven prosperity fuels the most ambitious experience of urban sustainability: the new city of Masdar, designed by Foster & Partners.

The Burj Khalifa broke in Dubai the world height record, while the Emirate went bankrupt; another Gulf Emirate, Abu Dhabi, which in sharp contrast promotes horizontal model cities like Masdar, came to its rescue.

The contradictory nature of the times is also present in Spain, where the depth of the crisis, which has devastated an oversized building sector and generated unemployment rates that double those of the European Union, has not provoked social conflictivity or an articulatepublic debate, with political leaders tangled up in mutual accusations of corruption, while the increasing debt of the State places in an imprecise future the costs of adaptation to a world that has changed for good.

The Oslo opera house, a work by the Norwegian studio Snøhetta, obtained the influential Mies van der Rohe Award, while the Swiss Peter Zumthor (below, his lyrical chapel in Mechernich) received the coveted Pritzker Prize.

In such context it is hard to make a balance of the year marking only the events and an- niversaries, distinctions and disappearances, competitions and building completions. Under the impact of the Great Recession, the first decade of the 21st century has come to a close with an ash aftertaste, and the efforts to tag it – from lost decade to double zero decade – evidence that, beyond the boom of social networks, the doors opened by the decoding of the human genome or the advances of artificial intelligence, the closing bars of the analogical era are stained with skepticism and anxiety: we are entering a new period that cannot be explained in a routinary manner, but we do not know if we should yearn it or fear it.

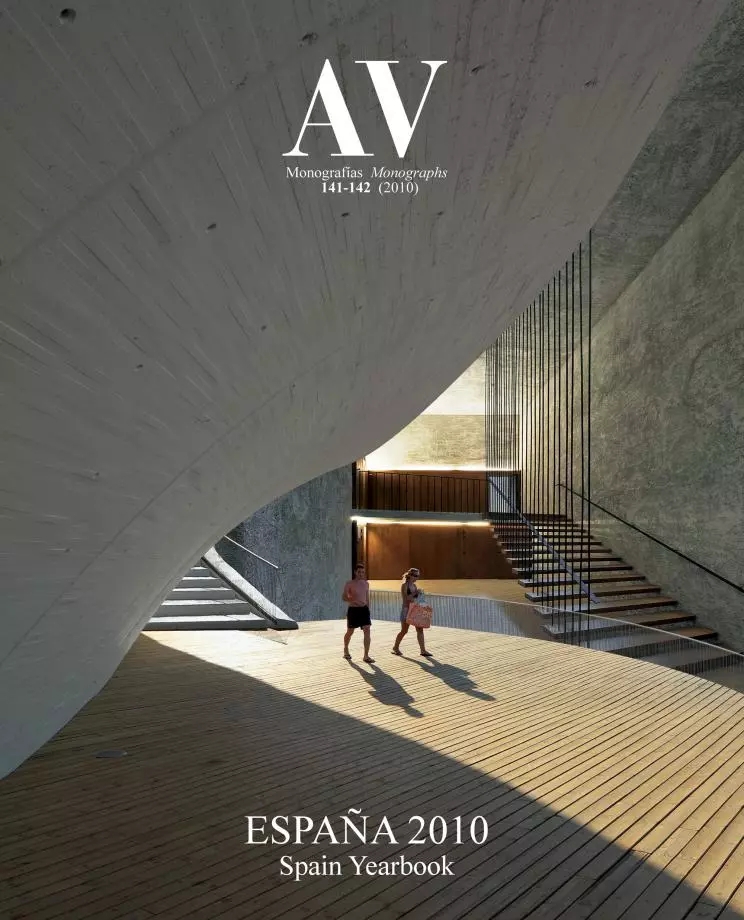

Two of the most awaited museum inaugurations were that of the Art Institute of Chicago, by the Genoese Renzo Piano, and that of the MAXXI of Rome (below, the void over the lobby), by the Anglo-Iraki Zaha Hadid.

However, we must obediently remember that the second centennial of Charles Darwin – and the 150 anniversary of The Origin of Species, which had such a strong influence on the evolutionary conception of design – coincided with the first of futurism, an ambiguous movement that we are bringing back with caution, and with the centennials of figures like the architect and critic Ernesto Rogers, whom we know from the firm BBPR, but also for his role as director of Casabella (a magazine that, along with Domus, celebrated its 80th anniversary); the engineer Fritz Leonhardt, who built essential works during the Nazi period and in democracy; or the landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx, inseparable from the young Brazil that raised Brasilia, a new city that now turns 50: the same age as Wright’s Guggenheim, celebrated with an exhibition about the master that travelled from New York to Bilbao, crossing the Atlantic in the opposite direction to the one commemorating the 90 years of the Bauhaus, which premiered in Berlin to later visit the MoMA.

Beyond anniversaries, the embers of China’s year lit up the image of the CCTV complex in flames: one of the iconic works of the olympic Beijing – designed by Rem Koolhaas – par- tially destroyed after hit by fireworks. All of these circumstances contribute to generating a partial view of the affirmative vigor and hes- itant fragility of the new superpower, admired for its economic growth and criticized for its democratic defficiencies; reproaches that have not prevented ‘The Middle Kingdom’ from establishing with the United States the G-2 that heads the planet today.

The Magic Box (below), by Dominique Perrault, did not win for Madrid the Games of 2016. Francisco Mangado, who finished in Vitoria another metal box, received the Spanish Architecture Award for his Pavilion.

Undoubtedly, this still inefficient global governance has new key players, in particular emerging countries like India, Indonesia, South Africa and Brazil, that faced with Japanese glaciation, Russian implosion and European paralysis are called to play a more prominent role, often stressed – as in China – by major sports events. This is the case of the 2010 World Cup in South Africa, with new stadiums built in Johannesburg, Cape City, Port Elizabeth and Durban; or the 2014 World Cup in Brazil, strengthening the continental leadership that won the 2016 Olympic Games for Rio, competing with Obama’s Chicago, but also with Tokyo and Madrid, a city that had supported its candidacy with the opening of the Magic Box of Dominique Perrault, a tennis center whose construction was fostered by the international successes of the Spanish ‘Armada’.

The year also had the usual list of prizes, with the Pritzker at the lead, picked up by a se- vere Peter Zumthor, and the Mies, which went to the Oslo Opera House, a horizontal, urban piece by the studio Snøhetta; the Portuguese Álvaro Siza received both the British and the French golds, while the American gold was presented to the Australian Glenn Murcutt; the Anglo-Iraqi Zaha Hadid, who completed the MAXXI in Rome, was awarded the Praemium Imperiale, and the American Steven Holl, who inaugurated the Knut Hamsun Museum in the Norway of his ancestors, was the first recipient of the generously endowed prize of the BBVA Foundation; the British Norman Foster,who inaugurated in Madrid the first compre- hensive exhibition of his drawings, was distinguished with the Prince of Asturias Prize for the Arts, being the fourth architect who receives this award, the most prestigious of Spain, where the professional associations also commended two recent works: the Canal Theater in Madrid, a project by Juan Navarro Baldeweg which received the Biennial prize, and the Spanish Pavilion in Zaragoza, a building by Francisco Mangado which was awarded the Spanish Architecture Prize, while he completed another two significant works, the Ávila Congress Center and the Álava Archalological Museum in Vitoria.

Santiago Calatrava completed in Liege a light and monumental station for high-speed trains (above), while Juan Herreros won in Oslo the competition to build, by the acclaimed seaside opera house, the Munch Museum (above).

The list of completed works, aside from those mentioned above, should include the Acropolis Museum by Bernard Tschumi in Athens; the Pinault Foundation by Tadao Ando in Venice; the Art Institute by Renzo Piano in Chicago; and the museums by David Chipperfield in Anchorage, Gigon & Guyer in Lucerne, Sauerbruch & Hutton in Munich or Delugan & Meissl in Stuttgart; as well as the station by Santiago Calatrava in Liege; the waterfront by Carlos Ferrater in Benidorm; the library and stadium by Toyo Ito in Hachioji and Kaohsiung; or the unique hypostyle space of Junya Ishigami in Kanagawa. In the area of competitions, we must mention the successes of David Adjaye in the Museum of African American History of Washington; of Steven Holl in the extension of the Glasgow School of Art; of Christian Kerez in the headquarters of Holcim; of Nieto & Sobejano in the Visual Arts Center in Madrid; of Guillermo Vázquez Consuegra and Carme Pinós in the CaixaForums of Seville and Zaragoza; of Esteve Bonell in the Parliament of Lausanne; and of Juan Herreros in Oslo’s Munch Museum, next to the award-winning opera house.

But the year also leaves behind a sad trail of disappearances: architects like the Czech Jan Kaplicky, founder of the studio Future Systems; the Norwegian Sverre Fehn, Pritzker Prize in 1997 for a scarce and exquisite oeuvre; the Canadian Arthur Erickson, who shaped Vancouver with his muscular constructions; the French Neocorbusian Michel Kagan; or the Americans Charles Gwathmey, a member of the mythical New York Five, and Malcolm Wells, pioneer of ecological architecture; photographers like Julius Shulman, who created the myth of the American West Coast; and editors like Monica Pidgeon, director of AD during its best years. Aside from our own Luis Peña Ganchegui, the Basque author with Chillida of El Peine de los Vientos; Alfons Milá, member of the Catalonian saga that joined architecture and interior design; Javier Lahuerta, master of structural calculation; and the lamented Juan Antonio Ramírez, the art and architecture historian who disappeared prematurely leaving behind a colossal intellectual heritage. Now that the cold has come, with economic recession and a reaction against the pyrotechnical excesses of the times of ostentatious prosperity, the much needed critical debate will miss voices like his.