Fracture Lines

The proliferation of broken shapes vibrates in odd resonance with the pangs of a year marked by Islamist terror, which surfaced tragically in Madrid’s 11-M.

The clash of civilizations predicted by Huntington is becoming a standard measure to interpret the cracks of the globe: the agitation of the Slav world within its blurred perimeter, the rivalry between China and the United States or, above all, the violent conflict between the Muslim universe and the Judeo-Christian West. But this self-fulfilling prophecy reproduces its cracks in the interior of the tectonic plates of the cultural blocks and, while the American professor is concerned about the segregated heterogeneity that the growing population of Hispanic origin is bringing into his country, other clefts, of the political sort, open up in the West: between the United States and Europe, within the United States between the rural areas of the interior and the urban areas of both coasts, and within a Europe enlarged to 25 members, between those devout and those reluctant to the Atlantic bond. This panorama of shifts and fractures finds a fitting symbolic representation in a broken and turbulent architecture, whose unstable balance recalls the instability of a world shaken by terror without boundaries and war without frontiers.

While Madrid suffered the train bombings in Atocha and opened the new Barajas terminal, OMA’s ‘Stealth aesthetic’ took shape in the fractured works of Porto and Seattle.

Winter on the Tracks

Spain’s long winter would come to an end with the election that bid farewell to Aznar, architecturally staged by the president at the new Barajas airport terminal, a colossal structure of metal gulls painted in the colors of the rainbow by Rogers and Lamela, which was hastily inaugurated for the occasion; however, the final performance of the politician would take place rather on the tracks of Atocha Station, the destination of the four trains attacked by Islamist terrorism with the tragic balance of 192 dead and 1,500 wounded: the attack of 11 March would cast its shadow over the polls of the 14th and the life of the nation thereafter, turning the brick lantern of Rafael Moneo into an impromptu memorial for the victims. In architecture’s small planet, the star was Rem Koolhaas, who received the Gold Medal of the Royal Institute of British Architects while his macro-exhibition in Berlin was still open, and the inaugurations of his works followed one another: after the Netherlands Embassy in the German capital and the Campus Center at Chicago’s IIT, the spectacular library of Seattle was greeted with the same critical acclaim expected for the soon to be completed Casa da Música in Porto, two faceted pieces of Stealth aesthetic which pedagogically materialize the shattered mood of the times.

Spring in High Grounds

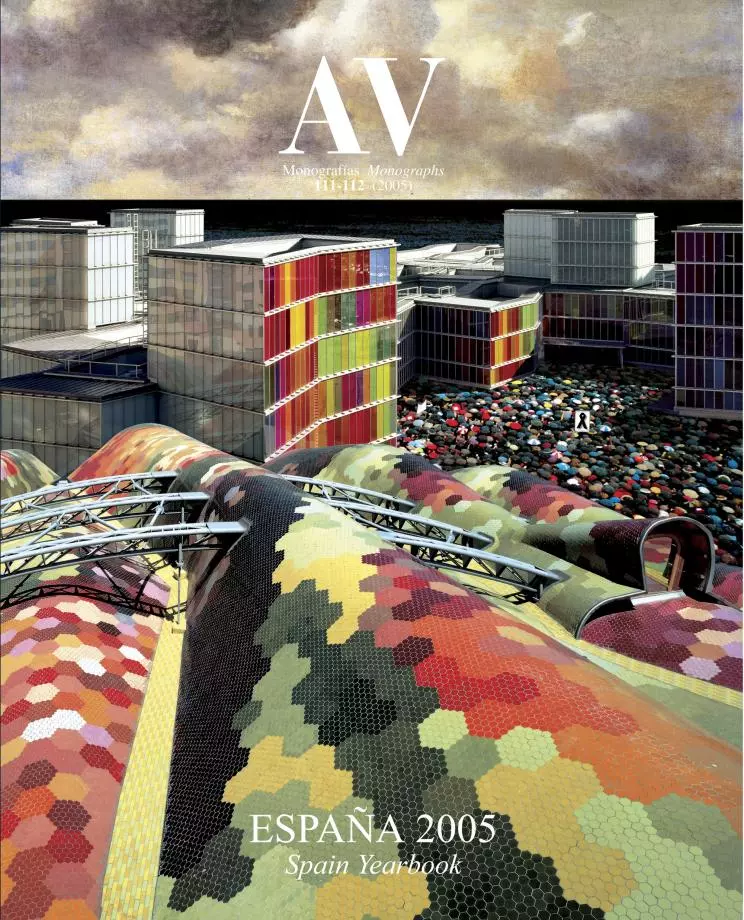

The London-based Iraqi Zaha Hadid was distinguished with a controversial Pritzker Prize while the occupation by the United States of her home country got tangled up in an endless war of attrition marked by the beheading of hostages and the tortures on prisoners, filmed and photographed to the disbelief of the world; other international distinctions went to Óscar Niemeyer (Praemium Imperiale) and Gilles Perraudin (Tessenow Medal), while the Spanish Gold Medal went to Luis Peña Ganchegui, the French Grand Prix to Patrick Berger, and the British Stirling Prize to Norman Foster for his shell-shaped Swiss Re tower, turning our attention away from the political and military shakes of the hour. Spain also healed the wounds of 11-M with a wedding in Madrid and a celebration in Barcelona: in the Almudena Cathedral – a work of several styles initiated a century ago, but completed recently by Fernando Chueca, architect and historian that would pass away before the year ended, and with walls and stained glass windows decorated by Kiko Argüello, an extravagant Catholic leader –, that shapes with the Royal Palace the monumental profile of the capital, the Crown Prince wed a TV news reporter; and in the new Forum of Cultures – built by the sea to boost urban development, on top of a sewage plant and with a triangular building by Herzog & de Meuron as central piece – an international cultural fair was launched, with activities lasting all summer long, and which would leave a bittersweet aftertaste.

The hovering volumes of H&deM’s Forum Building ( below), Wolfsburg Science Center and the Scottish Parliament represent the Barcelona event, Hadid’s Pritzker and the polemic posthumous success of Miralles. For their part, the stadium by Souto de Moura in Braga and that of Calatrava in Athens symbolize the two major sports events of the summer, the Eurocup and the Olympic Games.

Summer in the Stadiums

Inevitably, this season was marked by sports events, and both the European football championship in Portugal and the Athens Olympic Games would leave emblematic architectures: Eduardo Souto de Moura raised in a quarry the stadium of Braga, the most significant of those designed for the competition; and Santiago Calatrava lifted the huge roof held by arches of an olympic stadium built in a race against the clock to meet the deadlines, and that would become the best symbol of these games on their return to their Hellenic origins. The Ground Zero saga continued with commissions for the construction of several memorials and commemorative buildings to Michael Arad with Peter Walker, Frank Gehry and the Norwegian office Snøhetta, threatening to turn the site of the tragedy into a real-estate theme park; and in Spain, the premature inauguration of the Barajas terminal was followed by those of the Reina Sofía extension by Jean Nouvel and the MUSAC by Mansilla & Tuñón, two museums of contemporary art in Madrid and León that show public support of avant-garde culture.

Autumn in the Canals

Venice was the most popular destination of the autumn, with a stormy Biennial that celebrated the career of Peter Eisenman – in the year of the centenary of his much admired Terragni –, the works of Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa, and the critical mood of the Belgian pavilion. For their part, the most controversial openings were those of the Scottish Parliament in Edinburgh, a posthumous work of Enric Miralles whose budgetary chaos spurred a political inquiry; and that of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, remodeled and extended by Yoshio Taniguchi with sober laconicism, and inaugurated – as the library built by Polshek for Clinton – after the heated elections that gave George Bush four more years at the White House. In this last season, the disappearance of Jacques Derrida – whose philosophy of deconstruction inspired an architecture of fractured forms – was the coda of an obituary list that included the Europeans Kleihues, Belgiojoso, Reiner and Steidle, and the Americans Koenig, Larrabee Barnes, Abramovitz and Fay Jones, besides the great photographer Ezra Stoller: the buildings frozen before his lens trace the profile of an optimistic period, and of a modernity which still embraced a promise of emancipation. From the vanishing point of these first steps into the 21st century, a rational dream that has been displaced by the sleep of reason.