The law of the Land

Our landscapes deteriorate under the pressure of economic laws deemed indisputable, but that show their arbitrary nature when a crisis upsets the balance.

The law builds the landscape, but the land-scape does not build the law. Forgetting that nature is an artifice, some who indulge in the hermeneutics of natural law try to look for the ori-gin of law and normative order in the terrain. In Der Nomos der Erde of 1950, the political scientist and jurist Carl Schmitt identified “the law of the land” as the mythical foundation of justice, which emanates from the equity with which this law rewards the efforts of those who cultivate the land, from the patterns which divide the uses of territory, and from the physical limits that identify neighborhood, property and power. Similarly, many contemporary landscape professionals claim that in nature and agriculture lie the sources of legitimacy for a project of territorial organization inspired both by ecology and land art. But this law of the land is a law of place that acquires its sense and meaning from the marks left on the ground; it is not a law made legitimate by social agreement.

Social prosperity and competition among regions have triggered land demand in Europe, speeding up a process of suburban development that started in the sixties and that has shaped an anonymous landscape.

Confronted with the visual deterioration of city and countryside, European architects and urban planners look back to gardening and landscaping as curative disciplines. If urban form is determined by public works and municipal guidelines, and if the configuration of the rural expanse originates in the intersection of transport infrastructures and Brussels-imposed farm laws, perhaps it is best to intervene in the resulting environmental cacophony through the lazy but wise ways of nature itself: against the iron law of economy, the land law of ecology. This natural law, however, is extraordinarily artificial: the ecology of the landscape is human ecology, the law of the place is a set of regulations created by its inhabitants, and genius loci finally emerges from a pact among people. The intellectual and emotional recourse to the archaic order of the land diverts attention from the voluntary laws that build the landscape: its medicine is not a panacea, but a placebo..

Subject to the inexorable laws of exploitation, the agricultural arcadia of green pastures has turned into a menacing inferno of plagues, with massive sacrificing of animals whose corpses pile up in farms.

The current popularity of landscaping has its origins in the contemporary degradation of the landscape. Just as we only pay close attention to our own bodies when we are ill, we become fully aware of our surroundings only in times of crisis. Simultaneous signs of anxiety have been the European Landscape Convention, which was approved by the European Union in July 2000, the 2nd European Landscape Biennial, held in Barcelona in April 2001, and the Third Spring of Museums, which during the same month carried out landscape-related activities in nearly a thousand museums in France and elsewhere in Europe. As the limits between city and countryside blur, fraying the schemes of the urban fabric and contaminating the open spaces of the rural realm with random constructions, the existing landscape is transformed into an uncertain and heteroclite amalgam governed by the ever changing laws of profit and opportunism, and this spoilage that has gone unimpeded nourishes a clamor for what has gone.

In the past decade, the European territory has seen itself subjected to the combined pressure of social prosperity and regional competition, multiplying to unknown extremes the demand for space for residential use, work places, infrastructures and leisure premises, and extending the suburbaniza-tion process initiated in the sixties to the point of consuming enormous stretches of land. Some governments, such as Great Britain’s, have considered confronting this unprecedented phenomenon by prohibiting construction in intact areas – referred to as ‘green land’– and locating new developments in those previously built-on zones called ‘brown-fields’. Others, like the Netherlands’, endeavor to restore the contrast between urban and rural by drawing a ‘red line’ around existing population cores and not authorizing construction outside those perimeters. But neither the report Lord Rogers presented to the British Parliament nor the 5th Plan-ning Report of Holland’s Council of Ministers has the binding force of law. They are but expressions of the extent of Europe’s malaise.

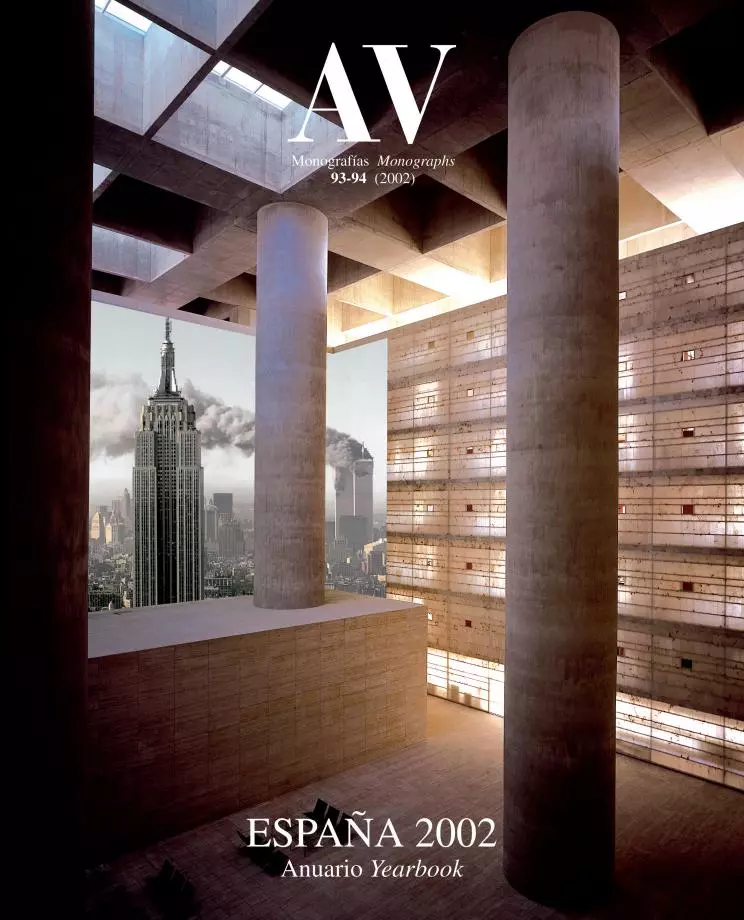

This territorial malaise is a blurred feeling of helplessness and impotence that ignites only when a sanitary emergency throws new light on the cruel organization and management of our agricultural Arcady, or when an unscrupulous municipal cor-poration exceeds the habitual degrees of urban degradation by cluttering the city with static and mobile publicity. From mad cows to foot-and-mouth disease, we have entered the 21st century under the glare of pyres of carcasses, mass sacrifices, and interminable pits that describe with ancient elo-quence the true nature of Europe’s rural landscape, a ferocious factory for the exploitation and extermination of the organic, while in the cities the urban landscape gets corrupted by formal decomposition and the treacherous siege of advertisers colonizing the symbolic universe from canopies, booths, and billboards, appropriating public space to assert the social importance of spectacle and consumerism: twin assaults on the two poles of the landscape that manifest both the hopeless fragility of our natural and cultural heritage and the essential indifference of its contemporary expression.

If the cities battle against environmental pollution, why not fight advertising pollution in the same way?The Cuban-born artist Félix González-Torres left a testimony of that rebellion in the silent poetry of his billboards.

These days, six Castellón billboards show an image by the New York-based Cuban artist Félix González-Torres which were displayed in 24 spots of his city back in 1992, four years before he died of AIDS. The mark of bodies on the empty bed is a haiku of political poetry that confronts the erosion of the public domain with a hint of the intimate realm, and alerts us to the vulnerability of individuals in the abrasive territory of a collective sphere whose impassive law no longer stops at the thresh-old of the private. It is hard not to have a similar feeling when contemplating the hecatomb of the French farm where bovine singularity has given way to a formless mass ready to be consumed in a propitiatory pyre, where Clarín’s Cordera, the cow who charged at the trains of Mayakovsky, and the literary animal of Monterroso will smelt in smoke on the way to the common grave in the clouds that Celan promised the victims of the Holocaust. Whether AIDS or foot-and-mouth disease, the silent conflagration of urban publicity or the nocturnal bonfires of farmlands, these epidemic landscapes do not reflect the violation of a natural law, but the violence of human law: an arbitrary law which we can in fact amend without having to return to the mythical authority of the law of the land. In the end we shall have the landscape we deserve, for the landscape is nothing but a voluntary geography.

¡Bring Down Those Billboards!

The insurgent gardens should stand up against the advertising billboards. The city of spectacle finds its most literal expression in these urban signs, and a rebellious landscape should choose them as their Place Vendôme Column: the symbol to tear down. Where there was a billboard, a vertical garden; against the screams of advertising, the whispers of vegetation. A more quiet town is a more inhabitable one: if we confront atmospheric, acoustic and luminous pollution, no less should we oppose the visual contamination of the city caused by the frenzy of commercial or political advertising. In the past institutions were represented through architecture and landscape; today they are represented through advertisements: our billboards are our Versailles. Their elimination is a modest and attainable goal: a law made them disappear from roads, and a statute can eradicate them from streets. With some exceptions indeed; the Osborne bull has urban cor-relates in some neon crossroads and movie bill-boards, but the current fascination with the Venturi of “Main Street is almost all right” should not make one think that “LasVegas is almost all right”. Times Square has served as an excuse for the colonization of the city by publicity which in most cases degrade the urban landscape. Let us plant ivy at the foot of every billboard and let us raise insurgent gardens: “Erased billboards”, a civic and artistic project in the spirit of the Beuys of Kassel. Let nature win over spectacle, and let Barcelona, pioneer in so many things, move from hard squares to soft billboards.

The small manifesto that follows was presented in the 2nd European Landscape Biennial, held inApril in Barcelona under the motto Insurgent Gardens.