Pilgrims gathering during the Kumbh Mela religious festival in Allahabad

This country-continent is already the world’s most populated. While humanity hit the 8 billion mark, India surpassed China, showing a demographic strength that contrasts with the decline of the Middle Kingdom, which for the first time in 60 years has seen its aging population decrease. India, with more than two thirds of its 1.4 billion at working age, is the fifth world economy, ahead of its old metropole, the UK, and during this decade will probably overtake Japan and Germany to become the third, only behind the US and China. This colossal boom, which however coexists with high levels of poverty, pollution, and corruption, has driven its emergence on the international political scene as a champion of multilateralism, equidistant from Washington and Moscow as leader of the ‘Global South,’ while at home Narendra Modi has replaced with Hindu nationalism the pluralist secularism defended by Nehru since independence.

The demographic sorpasso of the dragon by the elephant has put the spotlight on a civilization that, together with China, has been the center of the development of humankind up to the Industrial Revolution, and that today recovers, like its neighbor to the north, from a long period of decadence. With a young population, India may replace China as the world’s manufacturing hub, in a context where the US wants to weaken links with China, and where the Realpolitik of the elected autocrat, Modi, allows him to be part of the ‘Quad’ alliance with the United States, Australia, and Japan while at the same time refusing to sanction Russia, which still supplies oil, coal, and fertilizers at a good price. Besides this favorable international context, India profits from its inner strengths: excellence in education, highly qualified technical elites, and an entrepreneurial spirit that has won the country the third place in the ecosystem of startups.

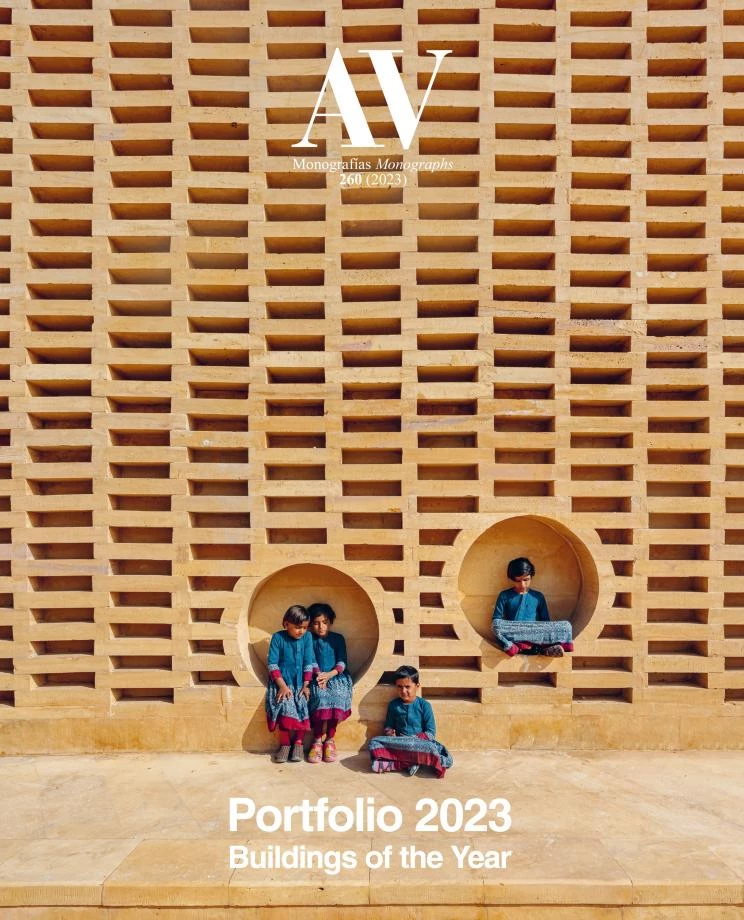

Economic liberalization since the 1990s has transformed a country no longer associated only with spirituality and underdevelopment, and which moves, as the writer Òscar Pujol vividly described, “with the slow trot of a majestic elephant.” The India of Rudyard Kipling or E. M. Forster was in our childhood that of Rabindranath Tagore, and later that of Salman Rushdie, Vikram Seth, or Arundhati Roy, whose god of small things was admired by those of us who shared her social and environmental concerns: a mythical and literary India that in the perception of architects is ill at ease with the great works of masters like Le Corbusier or Kahn, and not always found in the buildings by Balkrishna Doshi, Charles Correa, or Raj Rewal, but which shines in the informal settlements studied by Rahul Mehrotra, in the handcrafted works by Bijoy Jain, or in the organic pavilions by Anupama Kundoo, inhabited all of them by the god of things small in a big country.