Eccentric Albion

From the new Town Hall of London to the Space Center in Leicester, the last British works combine naïf futurism and traditional Anglosaxon eccentricity.

Before new labour's cool Britannia, the visionary Albion claims his rights: English imagination is sentimental. Sentimental is the recently completed Town Hall of London, a glassy head that faces the Thames through a zigzag mask; and sentimental too are Norman Foster’s latest projects for the British capital, the geodesic bullet-shaped skyscraper for Swiss Re in the City, and the infinite metal wave of the grandstand of Essex’s new race-track. Sentimental is the pneumatic and translucent tower of the Space Center in Leicester, which contains two colossal rockets in its cushioned silo; and sentimental was Nicholas Grimshaw’s previous work in the series of millennium milestones financed by the National Lottery, the Eden Project, a huge greenhouse that stretches its bubbling plastic roof over the pit of a Cornwall quarry. The eccentric, galactic futurism of these projects combines the old romantic and organic vein of British architecture with a sentiment of nostalgia for science fiction and the ecological Utopias of the sixties..

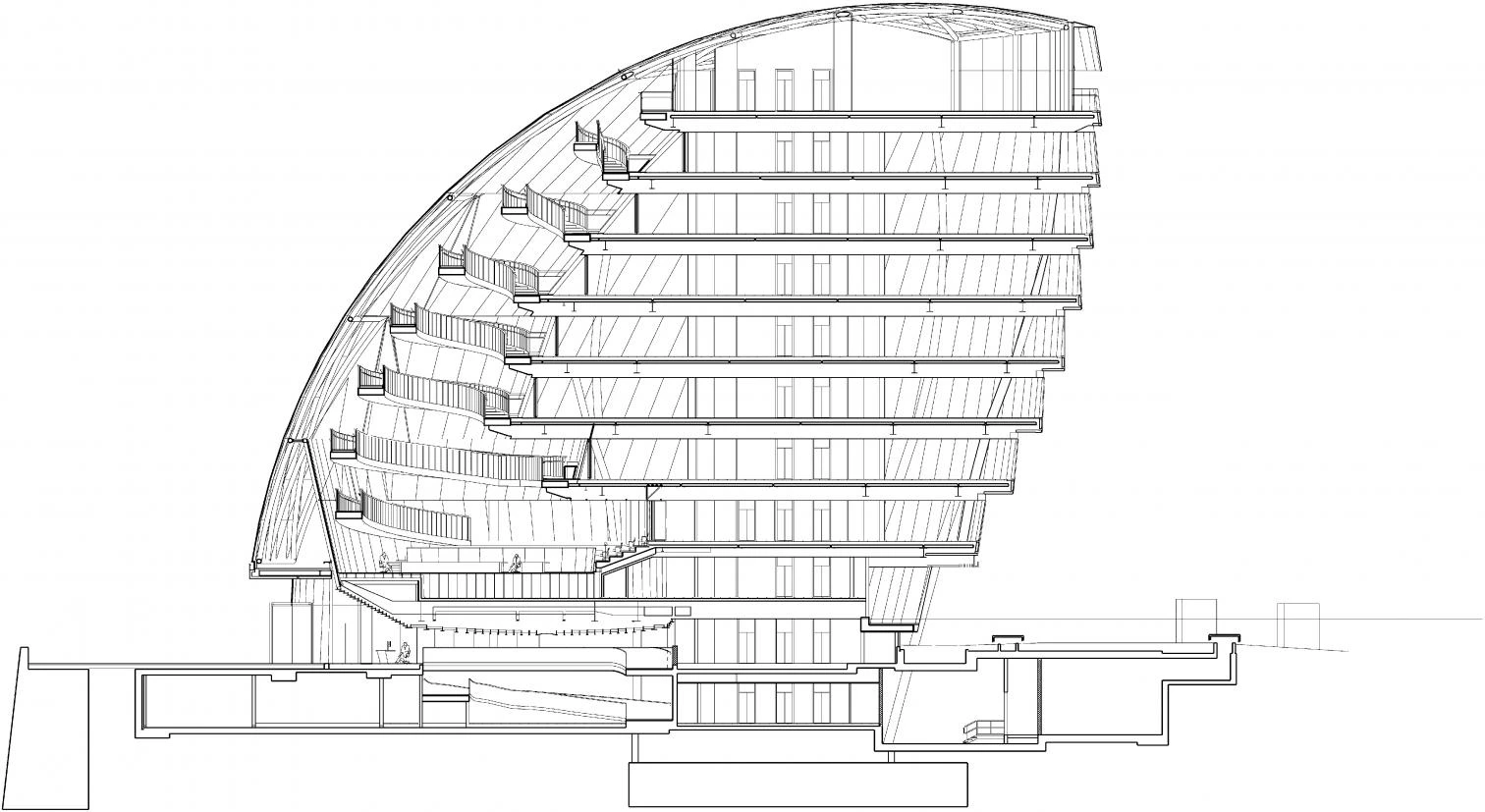

Evoking the utopias of the sixties in its fusion of the mechanic and the organic, Foster’s City Hall by the Thames claims its status of democratic institution with the ramp that places citizens above councillors in the assembly chamber.

London’s new Town Hall, indeed, is described by its author as a form borne almost exclusively out of energy and sustainability arguments. From the more or less hemispheric volume that makes it possible to minimize the surface to be sealed, thereby improving thermal management, to the contrast between the large glazed opening on the north and the staggered composition of the south facade, which avoids excess sunshine through the shadow cast by the successive breaks, most of the decisions taken in this project are related with the desire to create a model building that, being the seat of local power, should exemplify environmental responsibility. If to this ecological sensibility we add the transparency that many consider to be de rigeur in all democratic institutions, and the symbolic way of putting the citizens above their representatives, done here through a circulation ramp that spirals over the plenary session hall, then the ingredients of the recipe are not too unlike those of the Reichstag, and Foster has in fact used in this smaller work many of the ideas and the team involved in the construction of the German parliament.

Unfortunately, the final result is not as brilliant as that attained in Berlin, and despite the technical feat of executing its complex geometry and the demanding perfection of the finishes in a private development (the London Town Hall is just a tenant, in tune with the privatizing fever of Blair’s Labour), British architects recently elected the municipal headquarters as one of the least appreciated among contemporary works. And this occurred in a survey where Renzo Piano and Norman Foster himself (whose recent Praemium Imperiale has allowed him to complete the architectural grand slam) turned out to be the two most admired among living architects, and where a work of the latter was found to be among the favorites of those interviewed – the British Museum, with its large where Renzo Piano and Norman Foster himself (whose recent Praemium Imperiale has allowed him to complete the architectural grand slam) turned out to be the two most admired among living architects, and where a work of the latter was found to be among the favorites of those interviewed – the British Museum, with its large warped glass canopy floating over the courtyard.

Be it a crashed spacecraft, as described by Ken Shuttleworth, the partner in charge of the project, or a glass testicle, as called by Ken Livingstone, the mayor who now occupies it, the London Town Hall is not its architect’s finest work. Both the clumsiness of the volume and the uncomfortable encounter between the strips of windows and the triangulated shell of the lookout (from which one can see the Tower of London and another Foster project that uses the same geodesic structure with greater force, the Swiss Re headquarters, popularly known as the ‘gherkin’) damage the formal result of a building that, nevertheless, has the candid charm of science fiction, evoking at once the organic mechanism of a medieval helmet and the mechanical organism of an interplanetary shuttle, among whose spiral rings it is easy to imagine Fritz Lang’s Maria or Superman’s scoundrels, inevitable inhabitants of a me-tropolis that is also a naive space odyssey.

Climatic reasons account for the singular shape and stepped southern side of the City Hall (below), whose terrace offers views onto another emblematic work by Foster: the geodesic tower for Swiss Re in the City (above).

The same childish fascination with the future underlies the Space Center of Leicester, a science mu-seum organized around a large plastic silo where satellites and rockets are displayed, and within whose amiable folds families and schoolchildren discover the poetry and adventure of space travel, a mythical and nostalgic journey where NASA astronauts mix with Flash Gordon characters. Built in the decaying edges of Leicester with the purpose of becoming the emblem of this Midlands city, just like Foster’s ‘armadillo’ for Glasgow or Daniel Libeskind’s War Museum for Manchester, the architect, Nicholas Grimshaw – trained by the way in Foster’s studio – chose the material he had successfully used in his extraordinarily popular Eden Project greenhouse: a transparent plastic known as ETFE (ethyltetrafluorethylene), used here as in-flatable three-layer pillows weighing only 1% of the equivalent glass cladding.

In the Eden Project of Cornwall (above) and in the National Space Centre of Leicester (below), Grimshaw has used cushions made of ETFE, a new transparent plastic material that helps to define its galactic image.

In Cornwall, this plastic film was arranged in small hexagonal bubbles that gave the work an air halfway between Buckminster Fuller’s technovisionary geodesic domes and the pneumatic archi-tectures of hippy festivals, putting the Eden in first place, along with Ronchamp, among the favorite buildings of British architects. In Leicester it takes the form of a pile of sausages that is inevitably perceived like a playfully obese organism, translucent like a titanic jellyfish and padded like the space suits of Tintin in the Moon. Nevertheless, as in Foster’s LondonTown Hall, the naive StarWars esthetic does not demean the rigorous effort to optimize energy flows in the building, which uses mechanisms of passive thermal control and a double pump air system that increases pressure in the cushioned construction whenever it must resist wind forces (the plastic sheet weighs less than the air inside it, and on its own lacks any resistance).

Similar in dimensions and budget – a little over 40 meters tall in both cases, and a total cost of about 60 million euros for the Town Hall, which is almost doubled in the Space Center only because the core exhibition space is there extended with several auxiliary constructions – the galactic bubble of London and the alien larva of Leicester testify to the imaginative vitality and experimental curiosity of a romantic and organic, pragmatic and visionary, sentimental and eccentricAlbion.The Cartesian rationalism of the continent would do well do pay heed to the strange isle of the English impatient.