Form follows Form

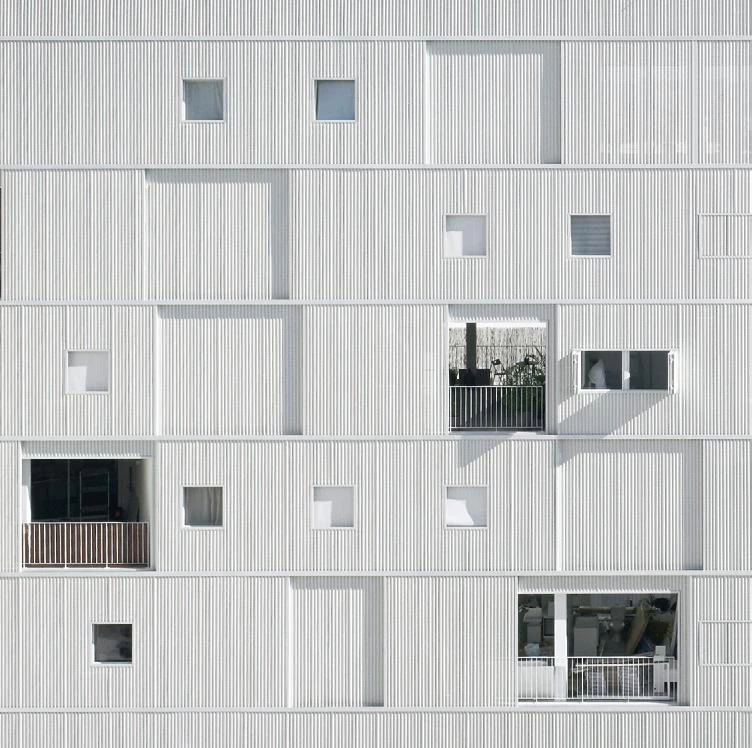

In the work of lan, form follows form. As in the line of Gertrude Stein – ‘Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose’ –, reiteration is a source of identity and emotion. She included the poem with the mythical quote in Geography and Plays, a book published in 1922. Three years before, Piedra y cielo, by the Spaniard Juan Ramón Jiménez, opened with his briefest poem – ‘No le toques ya más, que así es la rosa’ –, an aesthetic advice that the laconicism of Benoît Jallon and Umberto Napolitano also expresses with calm rigor. Between the repeated rose of Gertrude Stein and the naked rose of Juan Ramón Jiménez, the oeuvre of the Parisian studio turns form, multiplied and bare, into the conceptual frame of its exact and demanding work, which arrives at the lyrical rose after reducing architecture to urban geometry and material construction.

If their admired Aldo Rossi taught us how to understand the architecture of the city, Jallon and Napolitano extend his lessons to urban geometry, knowing like the Milanese that function follows form, and that form should always harbor the changing uses and vital shifts of societies and people over the course of history. Their architecture of prisms and skins is stubbornly urban in the insertion of its elemental forms in the tapestry of the city, and tirelessly experimental in the superficial articulation of its material envelopes, combining volumetric reiteration and expressive refinement in order to raise metaphysical, timeless, and hard objects like the bronze roses molded in wax by the Eupalinos of Paul Valéry, and inhabited by the turbulent, mutable flux of liquid life, mixing metals and roses with the help of fire.

The language of the urban constructions of Jallon and Napolitano is always neutral, abstract to the limit, and foreign to figuration because in them figure follows form, so their dialogue with the urban ground favors harmony over counterpoint. Musical in its rhythmic geometries, the architecture of the LAN partners, perhaps like Haussmann’s, whose radical transformation of Paris they have studied so closely, seeks the ‘poésie de l’ordre et de l’equilibre’ that the Préfet de la Seine mentions in his Mémoires as a guideline for his urbanistic activity. Seeing himself as administrator and artist, the Baron’s commitment to ‘régularisation,’ among so many opponents ‘peu coutumiers de la ligne droite,’ finds continuity in the work of these two architects determined to reach the poetry of the rose through straight lines, regular surfaces, and bold volumes.