It is near impossible to go through Ezra Stoller’s legacy of images without wondering how they have been interpreted by generations after him, given that second-hand perception and experience of architecture is particularly intense with the great modern works and the photographers who captured them. In the iconic character of that architecture, the architect’s genius merged with the craft of the photographer who froze his view in celluloid for posterity, imprinting the message of architecture of his time; a message that brought his epoch to his contemporaries, and brings us images of an era that has lasted way beyond its time.

While thinkers wanted to think and make us think modern architecture, the photographs taken by Stoller and his colleagues gave it to us. While Giedion, that disciple of Wölfflin who was CIAM secretary, tried to build a story about the modern genius, and while his student Norberg-Schulz tried to forge a logos of modernity, Stoller’s photos and those of his contemporary Shulman gave works a presence that could stand on its own. The new treatises – such as Space, Time and Architecture and Intentions in Architecture – addressed the near impossible task of documenting the emergence of a new formal system for the 20th century, in the current of new ideologies and philosophies of the phenomenon. In contrast, Stoller’s mission was, and is, to make us feel the power inherent in architecture, and the poetic might of the work itself. The photographs did not have to deal with the problems that the treatises did; they did not have to deliberate on the artistic situation that was so hard for the moderns to digest, and with the camera’s objectivity they concealed the art of the photographer who, like a virtuoso orchestra conductor, gives a magnificent rendition of the concerto. The discussion about architecture and photography as Art would come later, and only from the 1980s on, already retired, did he become the subject, as an artist of photography, of exhibitions. By then Stoller’s images, like the works they portrayed, had an unquestionable glorious past that gave them the aura of cultural heritage.

But most interesting about returning to the images is rediscovering Stoller’s connection to the architects: Mies, Le Corbusier, and that generation of moderns. An affinity which now enables us to connect with them too, in a process of updating the architectural experience of the period 1940-1960. With the works photographed by him, something happens, as in a poem or play: the experience that the author had condensed in them is reproduced when an interpreter transforms and updates it, just as Sophocles’s Oedipus was updated by Freud or Sartre, quoting Steiner. Stoller’s photos present works in their medium as a system of references, with powerful, explicit internal laws, and with a field including us: the photo situates the observer and gives him or her the photographer’s view, so he or she can appreciate the presence of the architecture, but also the relationship that the architect and the photographer had with the modern world then. A modern world envelops us and situates us in a universe where the work of architecture is given to us.

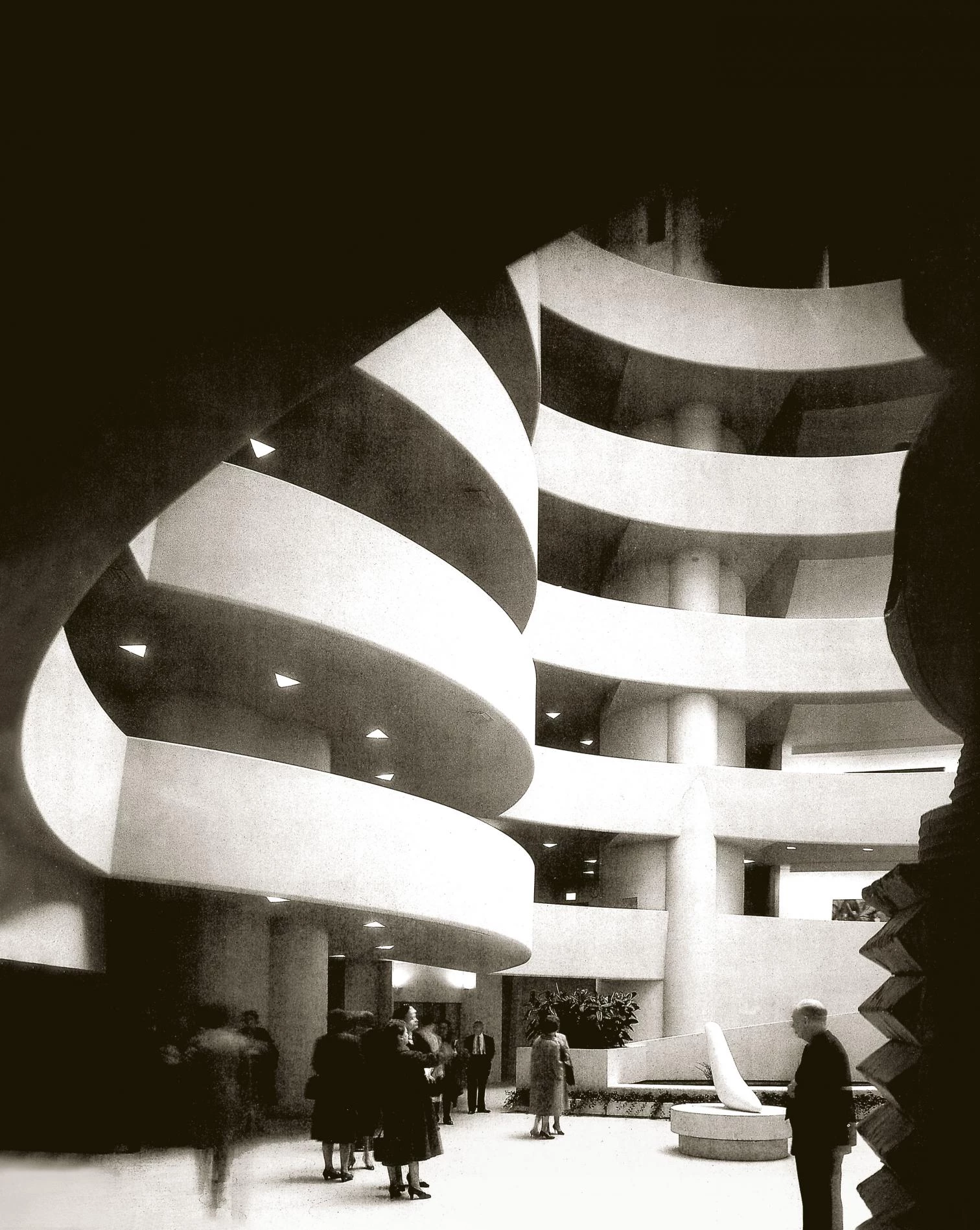

With his mastery of geometry and the chiaroscuro, Stoller also knew to capture the organicist versions of modernity, such as the Guggenheim Museum and the TWA terminal, both in New York.

Stoller’s world is that of a scholar of architecture and industrial design: an abstract, geometrical, vertical and horizontal world. The correction of verticals and the position of the horizon tell us how buildings are, how we think them out in plans, more than how we see them as they are. Clearness of detail adds an unreal perfection to a pre-corrected visual reality. The geometry of the buildings seems a permanent preoccupation of the photographer, and this could be why Stoller comes across as a classic. Even when he portrays the impossible curves of Saarinen’s TWA terminal, he composes them at the rectangular edge of the field-photo. The geometry subdues the shadow: a trick for capturing the abstract rationale of works, of their formal systems and intense material quality. The light that outlines straight surfaces and shapes curves is a light awaited, sought out, and filtered to give the work a near impossible, pure, clear-cut presence that brings us to an immediate perception of the architectural reality of Stoller’s modern champions. As if the work existed on its own, perfect and only for us, once it has gone through the magmatic process of its creation, imagination, and construction. This is why our memory retains his work better in black and white; it seems more intense, more modern, like movies of the 1930s or 1950s, like equations, or like the musical staff.

And yet a run-through reveals many premonitions of what was to come… From Saarinen’s curves to Utzon’s fragmentary shells, the photographer’s lens shows a latent desire for the rupture of modernity. And with Bunshaft’s hesitations for S.O.M. he gave us a view of the rhetorical path of postmodernity. So many precedents of the present which were revealed in canonical modern works thanks to the photographer’s craft, and which open new doors in the experience of architecture and photography.