Two hundred pages for 12 essays and a prologue, and almost as many for projects, drawings, and biographical notes, celebrate the oeuvre of the Madrid architect Luis Cubillo. This profuse anthology and tribute covers the works carried out by his practice in the course of a quarter-century, from the late postwar to the mid-1970s. The abundance of material exposes the architect to comparisons or assessments that a stricter selection may have eluded, but also speaks of an effort to consider the cultural context surrounding his career, and reflect the crop of architecture that arose during the 25 years of Spanish prosperity, from the timid shoots of stylistic and social modernity of the 1950s to what could be called the happy maturity of the master builders of the 1970s.

Thirteen essays ‘stage’ those two decades and a half while praising the work of Cubillo, who sometimes appears as part of the main discourse, and at other times as a secondary element. His output represents an entire period and throws light on its evolution, both as an oftimitated example and as a testimony thereof, moderate when compared with that of colleagues who marked the more daring episodes of Spanish architecture – so rich in milestones and great personalities during a golden age for architects.

The 13 texts more than complete the tribute: they inevitably overlap, and while offering different reflections on the period and protagonist, they often take the reader through the same paths and sources. Through them we can place Cubillo in his political, cultural, social, and technical milieu, in his voluntary functionalism and geometric dexterity. And although the viewpoint that connects opinions seems to be the balance between a personal preference for modern architecture and the profession’s submission to an obsolete tradition, this view may now feel like an overly current mythology.

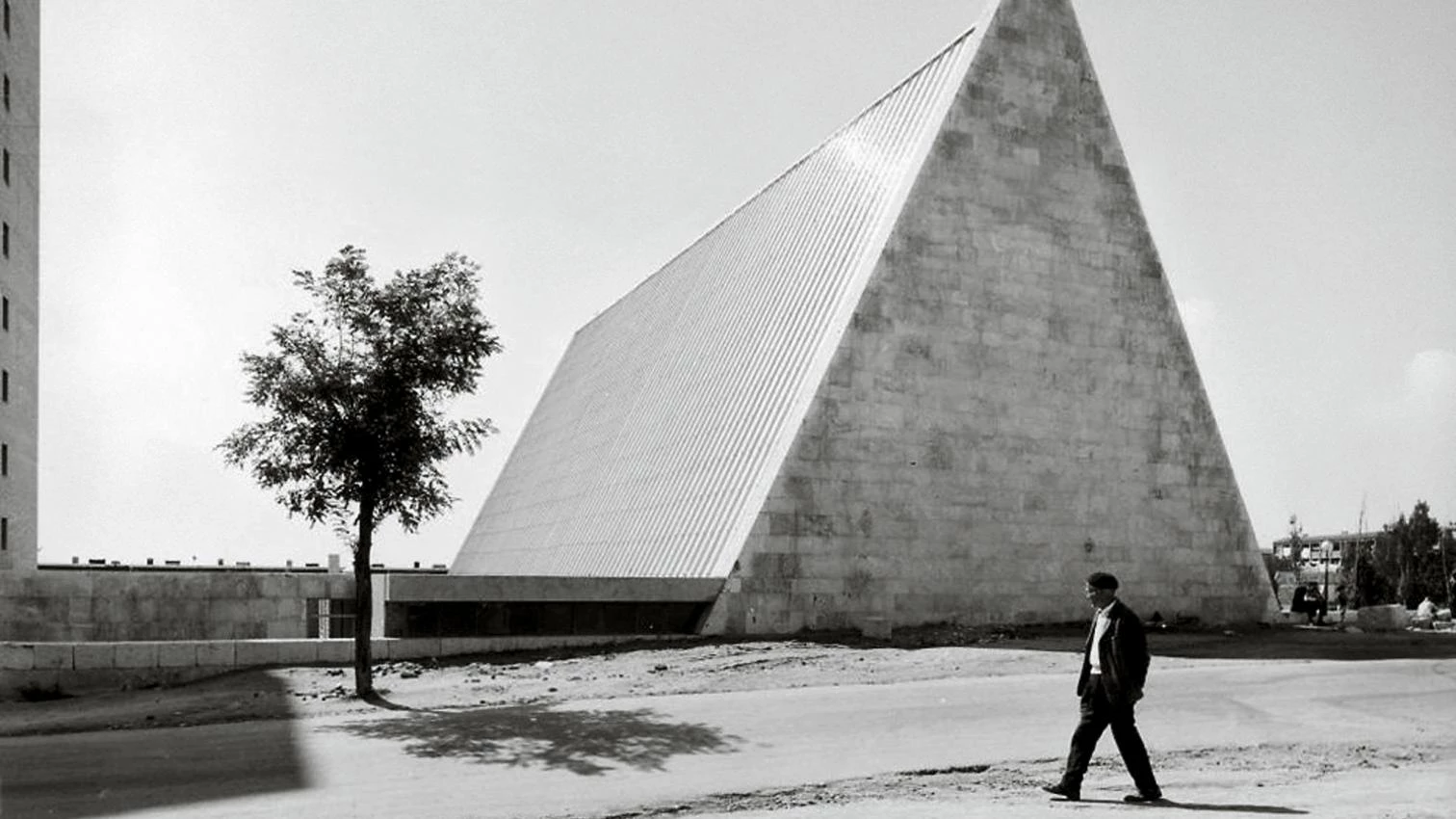

Maybe Luis Cubillo was not that sure about the myth of modernity. Photos and drawings seem to say that he knew where he wanted to be when the myth of architects was changing and the country was about to be reconstructed, when concrete, glass, steel, and the drawing took on a new meaning that was irresistible to young people like him. And in Spain’s new social system he did a good job, excelling especially in translating images of Nordic architecture in a Spanish code of very limited resources.

The book could not leave out the builder of churches, the Cubillo best known by the public thanks to the presence of his parish complexes in the city. And it is easy to grasp how he used his geometric experience to work out an image of change while fitting the immemorial time of the Catholic Church into modern times. Building sacred spaces within the Vatican reforms seemed a huge challenge – if not a contradiction – in the eyes of the most radical modernity, in times of the incipient critical theory of Zevi or Giedion. But Cubillo pulled it off amid all that, thanks to a gift for combining simple functional schemes, broken sections, and abstract, sculptural belfries.