Globe without Governance

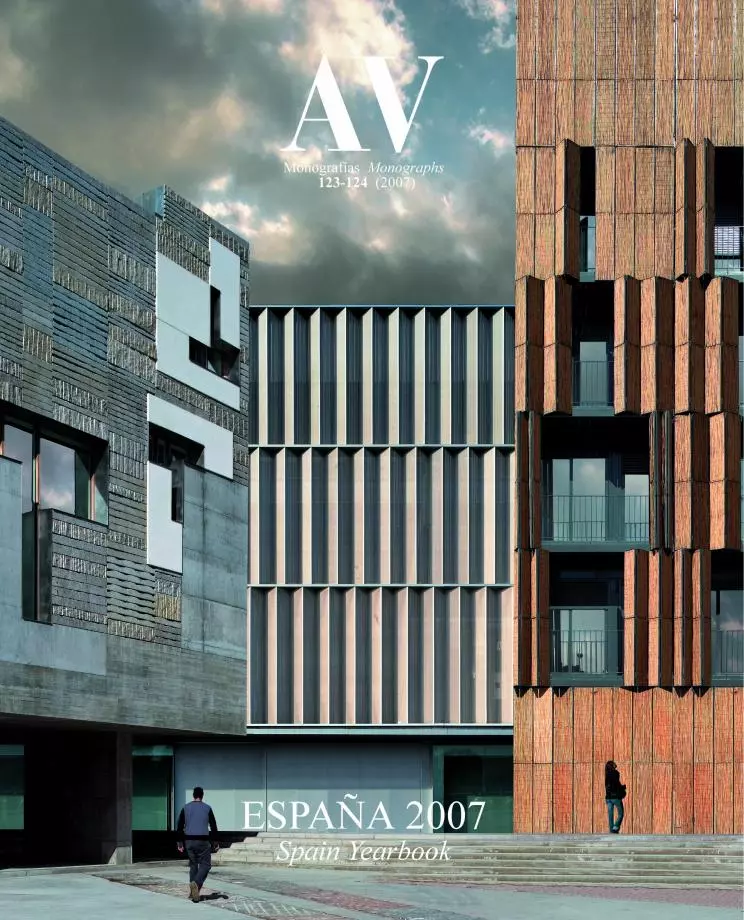

The MoMA exhibition, the Pritzker of Mendes da Rocha, the death of Fisac and the T-4 bombing were milestones of a year both affluent and chaotic.

Urban confusion reflects the disorder of the planet: both the ungovernable growth of cities and the increasing decay of the environment are symptoms of global anarchy, at a historic moment that witnesses at once the blurring of boundaries and the fading of rules. A world tangled up by flows that expand – from instant information or the flood of merchandise to the great migrations towards the Babelic megapolis –, and entrapped in a mesh of related crises – war, energy and climate –, experiences the discouragement of a political drift, a social fragmentation and an ideological decomposition that contrast with the fast-pace of the economies.

The new soaring skyline of Madrid and the new port for the America’s Cup in Valencia were icons of the Spanish building boom.

The material and symbolic conflict opened after 9/11 between the West and the Islamic world worsened as the year advanced, with Iraq’s immersion in a civil war marked by Saddam’s execution, the intensification of combat in Afghanistan, Palestine and Somalia, Iran’s atomic defiance and the rage of mosques after the speech in Aachen of a Pope that however travelled to Turkey, supporting the country’s entry in a mainly Christian European Union. The latter, which has still not overcome the consequences of enlargement and the failure of the Constitution, faced the renewed risk of its energy dependence, negotiating Russian supply while reconsidering nuclear options.

Iraq’s catastrophe had consequences in the United States, where the democrats obtained an absolute majority in both houses, in tune with the shifting opinion that has handed power to populist left-wings in several Latin American countries. There, both the death of Pinochet and Castro’s ailment heralded the autumn of despotic patriarchs, while the influence of the powerful northern neighbor weakened and that of its great geostrategic rival, China, strengthened. A country that kept gaining positions as much in this continent as in Africa, testing an alliance of civilizations quite different from that advocated by Kofi Annan and our own Zapatero.

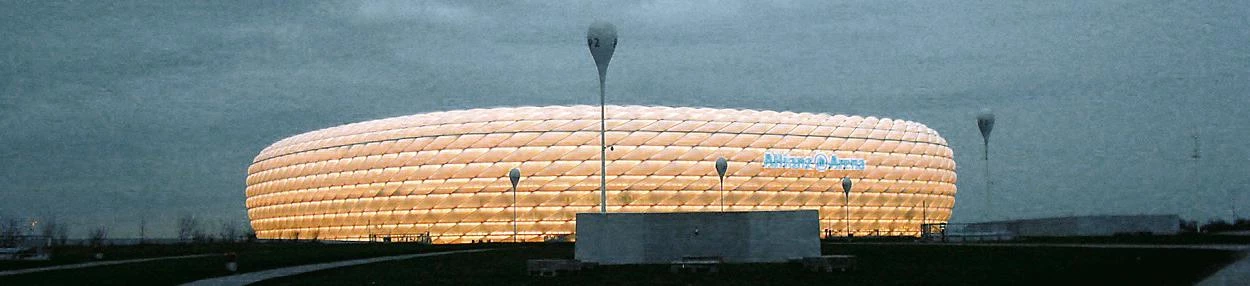

Germany hosted the soccer World Cup in new stadiums like the Allianz Arena in Munich by Herzog & de Meuron or refurbished ones like the Olympic Stadium in Berlin by Von Gerkan & Marg.

In Spain, the political year was marked by the fallout of the Catalan statute and regional elections that brought the debate to a standstill; by the harsh ideological confrontation sparked by the memory of the Civil War, which reached the death notices of newspapers; and, above all, by the reactivation of ETA’s terrorism, which destroyed one of the parking modules of the new terminal of Barajas Airport, leaving two dead. For its part, the social year was signalled by the effort to control the overflowing immigration; by the determination to reduce the number of deaths caused by tobacco use and traffic accidents with smoking bans and a point system driving license; and by the attempt to put a stop to urbanistic corruption in cities and coastal areas.

Many of the new fruits of Germanic prosperity are works of foreign architects such as SANAA with the School of Design in Essen or UNStudio with the Mercedes-Benz Museum in Stuttgart.

Fueled by a real-estate boom that started to show signs of cooling, the Spanish economy grew above the European average, experiencing a surge that benefited building companies, which made colossal acquisitions in the energy and services sectors, and boosted urban development both in Madrid – involved in public works of the scale of the M-30 ringroad or the Castellana skyscrapers – and in the remaining cities, and of course in those that prepare important events, be it Valencia – where David Chipperfield and b720 completed the main building of the marina for the America’s Cup of 2007 – or Zaragoza, which shall add to the projects already under way for the Expo 2008 a new museum in the heart of the city, designed by Herzog & de Meuron.

This urban effervescence – that has also caused controversies such as the defense of the trees lining Madrid’s Paseo del Prado – coincided with the architectural boom reflected in the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art of New York, opened there in February and presented later in Madrid, strengthening the collective selfesteem brought by the international successes of chefs like Adriá, film directors like Almodóvar and sportsmen like Gasol or Alonso: an exhibition that included the inevitable landmark of the year, Terminal 4 of Barajas Airport, which began its activity at the beginning of the year and was attacked by terrorism on 30 December 2006.

The United States saw the completion of significant works such as the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas by Steven Holl or the IAC headquarters alongside the Hudson’s waterfront in New York by Frank Gehry

Apart from that, the technically sophisticated light elegance of the airport terminal earned the highest British distinction, the Stirling Prize, and Richard Rogers, who designed the project with Madrid’s Estudio Lamela, also received the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement of the Venice Biennial. A chapter of awards that must also include the Pritzker Prize, presented to the Brazilian Paulo Mendes da Rocha in the Istanbul of Orhan Pamuk; the Praemium Imperiale, which went to the German Frei Otto; the Gold Medals of the RIBA and the AIA, awarded respectively to the Japanese Toyo Ito and to the Arizona architect Antoine Predock; and the Tessenow Medal, which distinguished the British studio Sergison Bates.

Already in our country, the FAD Award went to the Jaume Fuster Library in Barcelona, designed by Josep Llinás and Joan Vera, whereas the Gold Medal of the Spanish Architectural Association celebrated the career of Rafael Moneo – who completed the Bank of Spain extension in Madrid, an exemplary work for its subordination to history and context –, and the Camuñas Prize was delivered to the veteran Catalan architect Francesc Mitjans, sadly deceased shortly after; his name is added to a list of disappearances headed by the revered master from Castilla-La Mancha Miguel Fisac, and which also includes the Italian Anna Castelli, the German Simon Ungers, the Austrian and Australian Harry Seidler, the Japanese Kazuo Shinohara and the North Americans Hugh Stubbins and Sheldon Fox, as well as the critic of German origin Peter Blake and the urban activist in New York and Toronto Jane Jacobs.

The headlines of the year included colossal projects such as the winner in the Gazprom competition in Saint Petersburg, and small structures like the ephemeral pavilion of the Serpentine Gallery in London

The list of buildings of the year must necessarily include three German icons, all of them designed by foreigners: the fluid and dynamic Mercedes-Benz Museum in Stuttgart, by the Dutch Ben van Berkel and his UNStudio; the oneiric geometries of the School of Design in Essen, by the Japanese Sejima & Nishizawa; and the extraordinary Allianz Arena, a pneumatic and polychrome stadium by the Swiss Herzog & de Meuron – authors also of a singular project to extend the Tate Modern –that was inaugurated again for the summer’s soccer World Cup: an iconic sports facility which would be followed by the refurbishment of the Olympic Stadium of Berlin by Von Gerkan & Marg, the Palencia Stadium by Francisco Mangado and that of the Arizona Cardinals by Peter Eisenman.

In the United States – where Steven Holl, Morphosis, Libeskind or Diller & Scofidio completed significant buildings – it was also a good year for European architects, who finished important works: the French Jean Nouvel, who had opened in Paris the polemical Quai Branly Museum, also capped his first American building, the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis; the British Norman Foster, who had rounded off in Kazakhstan a monumental Pyramid of Peace, built in Manhattan for the Hearst corporation an elegant skyscraper, exquisite in its dialogue with context; and the Italian Renzo Piano, who is designing in the US a great many cultural centers, opened one of them in Manhattan, the delicately remodelled Morgan Library.

New York also witnessed the construction of the last work by Frank Gehry, an undulating corporate building facing the Hudson River that renews the language of the California architect, unlike the hotel built in La Rioja Alavesa for the Marqués de Riscal Wineries.

In spite of all this, the symbolic presence of high-rise buildings has slowly withdrawn from the Big Apple, with a new crop of skyscrapers that builds new Manhattans in Shanghai or Seoul, in São Paulo or New Delhi, in Moscow or Dubai, in a frenzied competition that no longer excludes cities such as Seville or Saint Petersburg, venues of competitions to erect colossal headquarters for ‘factual powers’, savings banks in the Andalusian case and the energy giant Gazprom in the Russian one.

As each year, in what is already becoming a tradition of exploration of new paths in architecture, London’s Serpentine Gallery built an ephemeral pavilion, and the person in charge this time was the Dutch Rem Koolhaas, whom along with the engineer Cecil Balmond and the artist Thomas Demand raised in Hyde Park a structure whose swollen lightness serves as visual metaphor of the world in which we live, a vulnerable bubble that is able to stay in place by maintaining air pressure in its translucent and empty interior, saturated with information and devoid of substance. We thought this would be the year of Mozart, but it has finally been the year of YouTube.