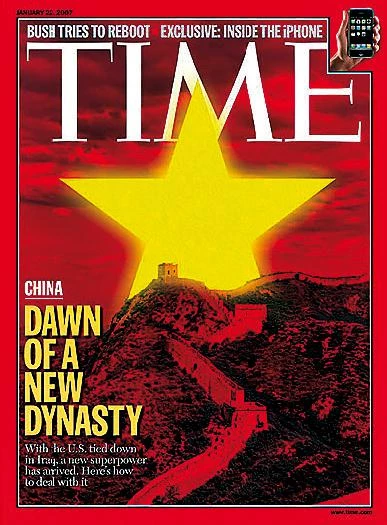

Asias Dawn

The financial crisis made the real estate bubble burst, in a year in which the Asian surge, from the Gulf to Beijing, did not erase the threat of global warming.

Asia used to be the future. Today it is the present. The mutation of the economic cycle has brought about a financial sorpasso that heralds political and military leadership for the continent. At the start of 2007, three of the world’s five largest banks, including the leader, were American, only one being Chinese. By the end of the year the situation was reversed, with three Chinese banks making it to the top five, one of them at the very lead, and an American bank coming in fifth. The mortgage crisis that wrought havoc in the United States in August burst the real estate bubble and sent Asian investment funds, whether from the Gulf or from Singapore, into western banks, creating a new panorama of economic power that is accentuated by China’s vigorous acquisitions in African and Latin American raw materials and energy. All this in the context of the decline of the dollar, the rise of oil prices, the universal conscience of a climate crisis and, to boot, the turbulences sparked by demographic and informational globalization, the lack of governance of the superpower, and the discrediting of democracy in the face of the authoritarian fundamentalism that has had its most menacing manifestation in a Pakistan shaken by Benazir Bhutto’s assassination.

Climate change caused by the greenhouse effect of CO2 emissions became visible in the dramatic shrinkage of glaciers all over the planet.

The little planet of architecture has tuned up with the world’s vibrations on at least two wavelengths: the urban and the symbolic. In the field of common construction, that which weaves the fabric of our cities, the collapse of housing developments marking the end of the real estate boom and the increased perception that architecture contributes to global warming have given rise to a new attitude of ecological sensibility that in Spain is reinforced by the debate on the hyper-development and the urbanistic corruption that together lead to the deterioration of coasts and of the areas surrounding cities. In the sphere of buildings of a more representational character, politicians remained keen on erecting symbolic structures, from the hopefully emerging Nicolas Sarkozy who chose to start his presidential mandate surrounded by architectural stars, or the renewedly powerful Vladimir Putin who flaunts Russia’s push with emblematic projects in Moscow and St. Petersburg, to the astronomically rich emirs of the Gulf, the prosperous autocrat Nursultan Nazarbayev of Kazakhstan, or the meritocratic hierarchs gracing the totalitarian capitalism of China, which in the Beijing Olympics will be showing off its heyday through a spectacular display of signature works, initiated this year with the opening of Paul Andreu’s opera house.

Both China and Russia undertook colossal works, from the National Theater, a titanium-clad ellipsoid completed by Paul Andreu in Beijing, to the Crystal Island, a huge tent-like structure designed by Norman Foster in Moscow.

As for other things, the year that marked the thirtieth anniversary of the Pompidou in Paris also saw one of its architects, Richard Rogers, accept the Pritzker Prize in a booming London, while the festivities marking the Guggenheim Bilbao’s first decade coincided with the spread of the popularity of Frank Gehry, who appeared in The Simpsons, was mentor to Brad Pitt, and designed jewelry for Tiffany, an eloquent illustration of how architects have embraced the pomp of celebrity in a way that has raised the artistic-mercantile value of their archives and brought about the sale in auction houses – along with Rothkos, Warhols, and Bacons – of works like Richard Neutra’s Kaufmann House, Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House, Jean Prouvé’s Tropicale, Pierre Koenig’s Case Study 21, or Marcel Breuer’s Wolfson Trailer; a business of domestic icons that contrasts with the donation to the National Trust of Philip Johnson’s Glass House, which opened to the public this year and has generated a long waiting list for visits to the mythical estate in New Canaan. In New York, meanwhile, the marriage of architects, money, and fame comes in the form of a downpour of luxury residential projects that is bringing in the profession’s entire elite, led by the Swiss partners Herzog & de Meuron – the other grand awardees of the year with their capping the RIBA Gold Medal and Japan’s Praemium Imperiale –, whose building on 40 Bond is a counterpoint of private opulence to two excellent executions of an eminently public nature, Renzo Piano’s skyscraper for The New York Times and SANAA’s small tower for the New Museum.

The tower by Renzo Piano for The New York Times and that by SANAA for the New Museum were the most important openings of the year in Manhattan, two works of public dimension that also seek urban regeneration.

In Europe, Coop Himmelb(l)au’s frozen whirlpool for BMW and the laconic materiality of Peter Zumthor’s museum in Cologne represent two aesthetic poles in between which falls the formal experimentalism that has had a generous laboratory in Germany, in tune with the innovating inclination of a Holland that has seen the likes of MVRDV, UNStudio, Jan Neutelings, or Erick van Egeraat complete outstanding works, and in contrast with a United Kingdom that has frustrated many of the expectations raised by London’s designation as Olympic venue, while the south of the continent celebrated the culmination of Bernard Tschumi’s Museum of the Acropolis and Rafael Moneo’s enlargement of the Prado Museum. The city of Madrid, where Thom Mayne and FOA completed singular social housing projects, was also the scene of some very notorious competitions – from the Ciudad de la Justicia, where Zaha Hadid landed the meatiest commission, to the convention center amid the four skyscrapers on the Paseo de la Castellana, which Mansilla & Tuñón won days after getting the Mies award for the MUSAC in León – as well as of some very tough controversies which, in the wake of the local and regional elections held in March, centered on municipal corruption networks, the invasion of the city by colossal advertising billboards and Juan Navarro Baldeweg’s dismissal from the Teatro del Canal project; the latter a bitter episode of discord between politicians and architects that happened to coincide with Santiago Calatrava’s tribulations in Valencia and Bilbao and the Galician Parliament enquiry on Peter Eisenman’s Ciudad de la Cultura in Santiago de Compostela.

In an old Europe where heritage is both a wealth and a restriction, masters like Zumthor or Moneo inaugurated museums in dialogue with the existing, that of Kolumba in Cologne and the extension of the Prado in Madrid.

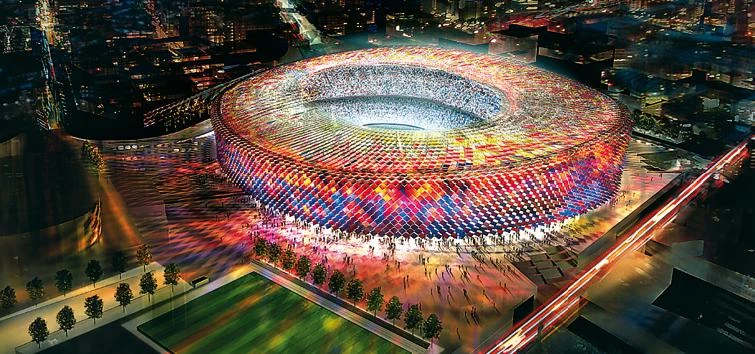

A collection of anecdotes of a year that in sports saw the America’s Cup being held in Valencia, in front of the Foredeck Building of a David Chipperfield who would end up with the Stirling Prize for his Museum of Literature in Marbach; and that with the Alonso/Hamilton rivalry nourished a passion for Formula 1 that served as an impulse for projects like the Ciudad del Motor of Alcañiz, commissioned by competition to the same Norman Foster who would push to renovate Barcelona’s Camp Nou. In culture, the year lived its summer Grand Tour of the arts lightly, greeted the launching of Lisbon’s Architecture Triennial – while the Portuguese European presidency managed to work out a promising treaty for the Union –, and celebrated Charles Eames’s centenary in simultaneity with the hundredth year of Oscar Niemeyer. But there was also a sad series of disappearances, with film losing Bergman and Antonioni, music Rostropovich and Pavarotti, philosophy Gorz and Rorty, literature Mailer and Gracq, journalism Umbral and Polanco, art Cuixart and Palazuelo, and architecture Livio Vacchini, Colin St John Wilson, Rogelio Salmona, Oswald Mathias Ungers, Kisho Kurokawa, and Ettore Sottsass. Public biographies that are now closed in the Wikipedia, in the course of an uncertain year that also witnessed the viral explosion of private lives in that reticular labyrinth we call Facebook.

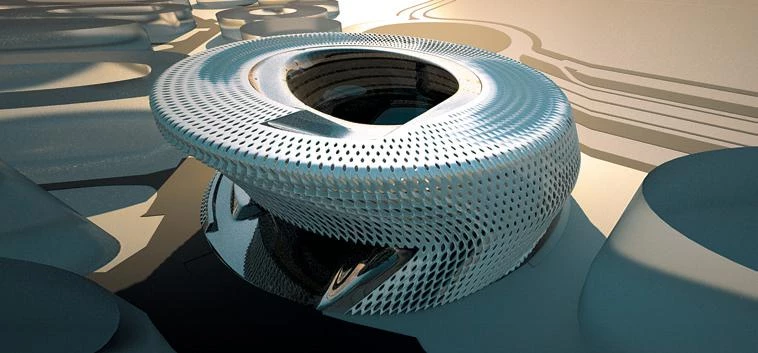

The completion in Munich of the whirlpool designed by Coop Himmelb(l)au for BMW coincided with the projects by Zaha Hadid for a courts building in Madrid and of Norman Foster for the stadium of the Barcelona soccer club.