The Airport and the Village

The Scottish Parliament, a work by the disappeared Miralles, has opened with praise for its lyrical language and controversy for its budget overruns.

Tuesday’s vote is between the airport and the village. The United States will elect a president, but they will also be choosing between two ways of life and two urban models. The most divided American electorate of the past quarter-century will decide between totemic figures, Democrat Kerry and Republican Bush, who, however, beyond their stands on the war in Iraq or the financing of health care, represent metropolitan cosmopolitanism and community essentialism, respectively. This cultural strife between the new Babylon of skyscrapers and the new Jerusalem of suburban communities finds its perfect architectural expression in the scenography of two recent films. One is Steven Spielberg’s The Terminal, which takes place entirely inside an airport: a California hangar was turned into a huge set for the filming of the story of a traveler trapped in a bureaucratic labyrinth. The other is M. Night Shyamalan’s The Village, inaccurately presented in Spain under the title El bosque (the forest), but set, precisely, in a fictitious 19th century village: a lost valley amongst the woods of Pennsylvania which served to accommodate the everyday life of a group of families isolated from the world.

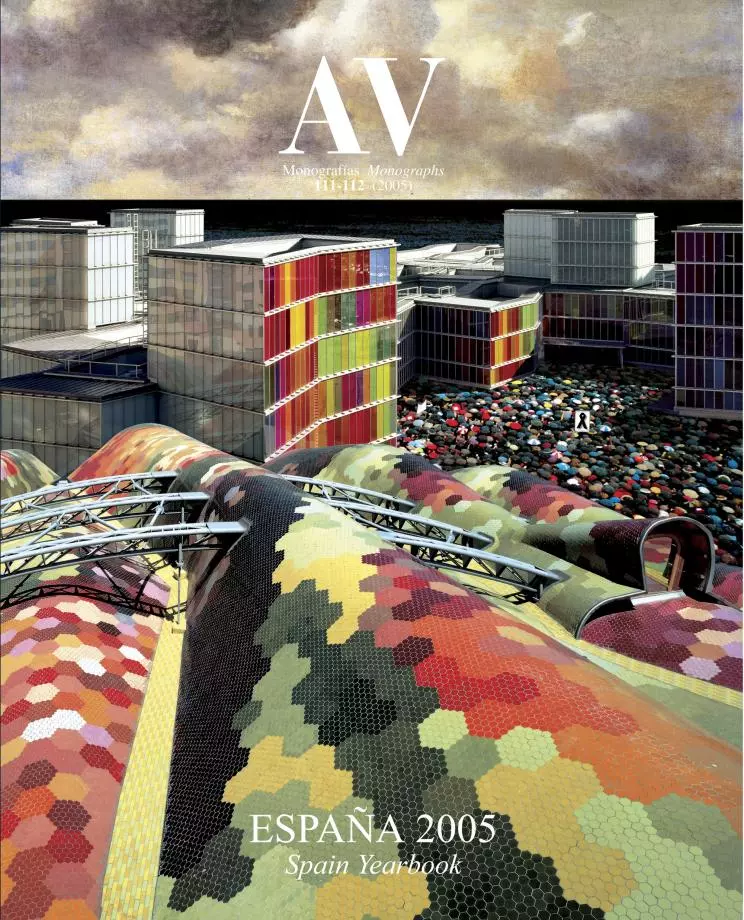

The set of the airport where Spielberg shot The Terminal is an accurate representation of the fast-paced metropolitan lifestyle and the cosmopolitan anonymity characteristic of secular societies.

The Brownian frenzy of the innumerable extras recruited in Los Angeles to represent the heteroclite multitude of an international airport contrasts with the peaceful existence and frozen time of the agrarian community, in the same way that the metal structure and the glass roofs designed by the artistic director Alex McDowell (who had already worked with Spielberg in Minority Report) are the architectural counterpoint of the farms and farmhouses built by the team of the production designer Tom Foden and the artistic director Michael Manson. In both cases the sets are convincing thanks to the use of authentic constructions. The Terminal required 650 tons of steel, real escalators, bona fide commercial franchises, and an organization that intelligently combined the tree-shaped supports and huge curved trusses of the latest generation of airports. For the village, in turn, the houses, the school, the bakery, the blacksmith’s or the meeting room had to be built with real foundations, and unlike the usual movie sets, they had to be totally functional, almost actually usable.

The idyllic agrarian settlement recreated for the shooting of Night Shyamalan’s The Village offers a fitting illustration of the community values associated with the essentialist nostalgia of suburban America.

Paradoxically, these plausible architectures are settings for unusual situations: an individual involuntarily imprisoned in a Kafkan junction, a community voluntarily locked up in an archaic utopia. But it is such exceptional situations, precisely, that make it possible to expose the contrived nature of real life or whatever truth there can be in a shared fiction. The executive producer of The Terminal is Andrew Niccol, producer and screenwriter of The Truman Show and director of Simone, two films that are emblems of contemporary simulation; and the director of The Village has built his own dream world with previous works like The Sixth Sense, Unbreakable and Signs. Pedagogically, the opposition between the hypermodern, hypertechnological architecture of the airport – which amalgamates recent examples of the likes of Norman Foster or Renzo Piano – and the timeless forms of the village – more premodern than postmodern, no matter how much it evokes the traditionalist essentialism of Aldo Rossi or Léon Krier – is a metaphor of the caesura between the secular cosmopolitanism of metropolitan America and the community nostalgia of suburban America: a confrontation between reason and faith that still describes the lines of fracture of the empire’s politics.

Nevertheless Viktor Navorski (Tom Hanks), star of The Terminal, is saved from the absurdity that a remote violence has thrown him into, thanks to the spontaneous solidarity of a small group of employees who in the anomy of the airport reconstruct the community spirit of the village. And Lucius Hunt (Joaquin Phoenix), main character of The Village, is spared from death through the rupture of isolation and a resorting to the technological means of outside civilization, ending the obscurantism of a community united by fear and myth with his exploratory and irreverent spirit. The airport and the village contain within them their own contradiction, and such ambiguity represents the stratified complexity of the USA’s current electoral dilemma better than the trivial simplifications that are making audiences choose between Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11 and Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ. Hillary Clinton can be a paradigmatic example of metropolitan rationality, but she did also write It Takes A Village to explain Democrat sensibility to the community fabric that is indispensable for raising a child; and Karl Rove may align conservative Christians to the Republican cause, yet that will not prevent multinationals, which have no other credo than money, from considering Bush their candidate.

Between the urbanity that civilizes or corrupts and the virtuous or immobile culture of the rural world is an old confrontation that, stretching America’s foundational puritanism with the contemporary emergence of evangelical fundamentalism, is perceived today under the ironic impact of the so-called “clash of civilizations”. Coined by the same Huntington that now warns us about the dangers of multiculturalism and immigration, this is a concept that ten years ago replaced Fukuyama’s voluntarist “end of history”. One same day of September, Aznar in Washington, D.C. and Zapatero in New York City expressed antithetical views regarding the aforementioned political and emotional struggle between Mars and Venus with a discursive elementality that avoided expressing either the extreme modernity of Christian and Islamic fundamentalism or the solid conservative foundations of secular rationalist pragmatism. Cosmopolitanism or piety, anonymity or identity, technology or tradition, airport or village: the masks of Halloween have already prognosticated the result, but the scriptwriter of this story, like García Márquez, maintains the suspense til the very end.