Historians weave histories with threads stringing a plot that tries to be objective, but both the plot and the threads are determined by personal preferences and a larger tapestry that covers everything and perhaps obscures it: the actual period in question.

The themes of the current period are many; these are ‘interesting times.’ Covid-19 aside, perhaps the most important is the climate emergency, which is shaping our consciences and setting the agenda of lots of fields, including architecture. And it has given rise to ‘environmental history, which poses methodological challenges but by its very nature may achieve what the best histories do: tackle not only the formal, but also the technical, social, cultural, and even economic dimensions of disciplines.

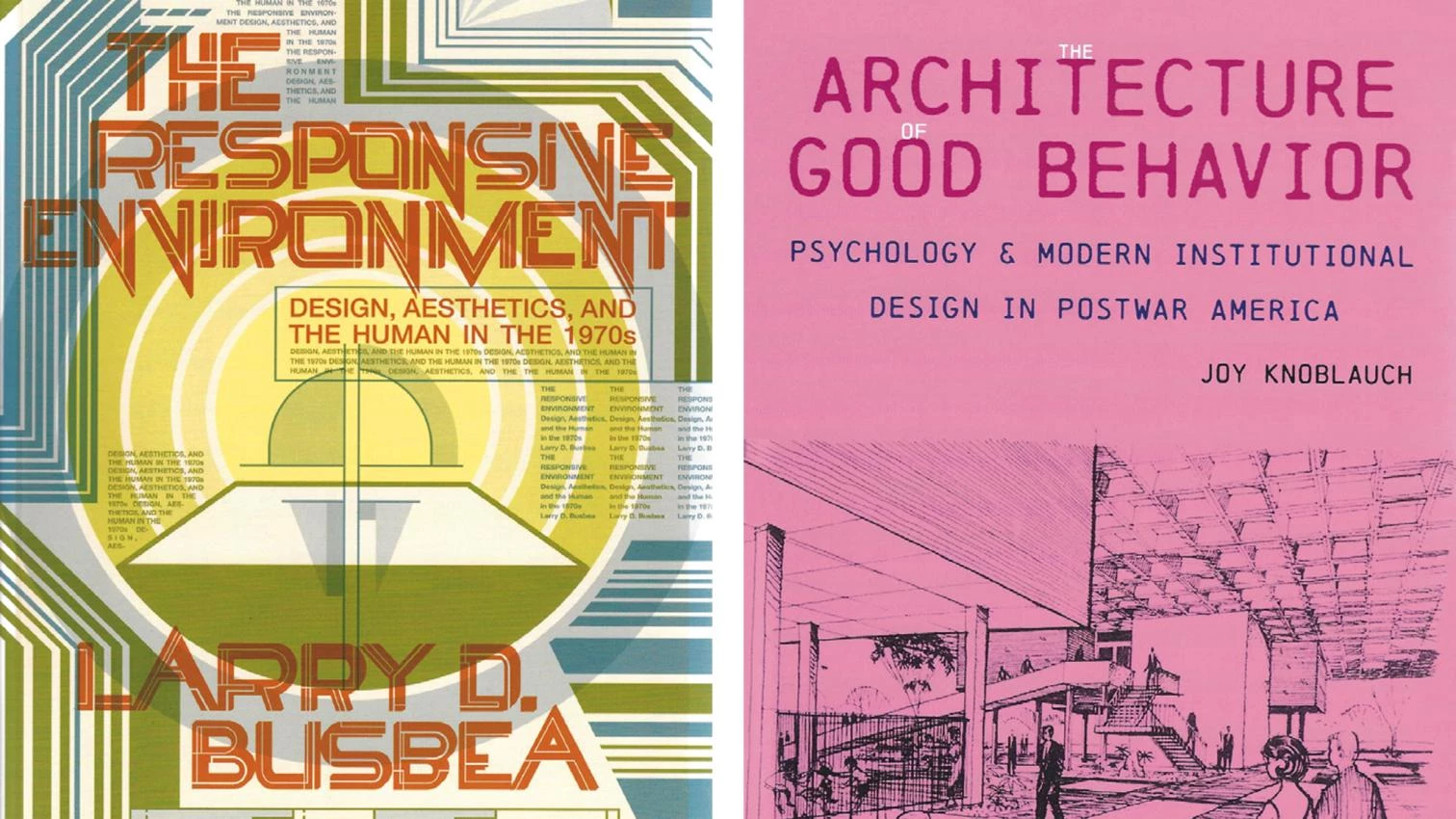

The Responsive Environment: Design, Aesthetics, and the Human Life in the 1970s and Architecture of Good Behavior: Psychology & Modern Institutional Design in Postwar America exemplify what to expect of environmental history when undertaken with rigor and talent. Both deal with a theme explored in the 1960s and 1970s, ‘environmental design,’ and do so from an ‘Americentric’ angle, but they pursue different, ultimately complementary approaches

The former focuses on psychological theories about the human body’s relationship with its habitat that proliferated in Gestalt times, and which led to a fashion that had its heyday in the 1970s, the years of ecological awakening, and in turn engendered countless design theories, art installations, conferences, and of course architecture projects. Busbea explains all this using the much used but nonetheless efficient recourse to ‘protagonists,’ from anthropologist Edward T. Hall, friend of McLuhan and Bucky Fuller and author of The Hidden Dimension in Architecture, to the young Nicholas Negroponte of ‘soft architecture,’ passing through Kepes and his Arts of the Environment or Soleri and his endearing hippy utopia Arcosanti.

What did these sometimes contradictory figures share? Confidence in the idea of architecture reaching the ‘total design’ ideal, just as the moderns wanted it but from a scientific base and using a new psychology – the body’s interaction with the environment – that applied as much on the scale of the home as on that of the city, even planet.

As Busbea shows, there was deterministic ingenuity in that confidence, and also ill-borne scientificism, and this is also shown in Architecture of Good Behavior, which unveils the environmental and also behavioral techniques that were deliberately used in the design of US institutional architecture in the period 1960-1980, when hospitals, schools, public housing, and prisons were a laboratory for experimenting with “psychological functionalism,” which, Knoblauch says, continues modernity’s rationalist legacy, but at the cost of promoting one of its more disturbing facets: the manipulation of human behavior through design. This was perhaps the prehistory of what we still do not look in the eye, even though we have already given it a name: surveillance capitalism.