Children’s toys have interested scholars of contemporary art for some time now. Curiosity about the theme is universal. As regards Spain, we remember the exhibitions curated by Carlos Pérez, ‘Infancia y arte moderno’ (Valencia, 1998) and ‘Los juguetes de las vanguardias’ (Málaga, 2012). Also the books Aladdin Toys: los juguetes de Torres-García (1998), and 3 Propuestas para niños: Ángel Ferrand, Emeterio Ruiz Melendreras y Tono. 1935-35 (1999).

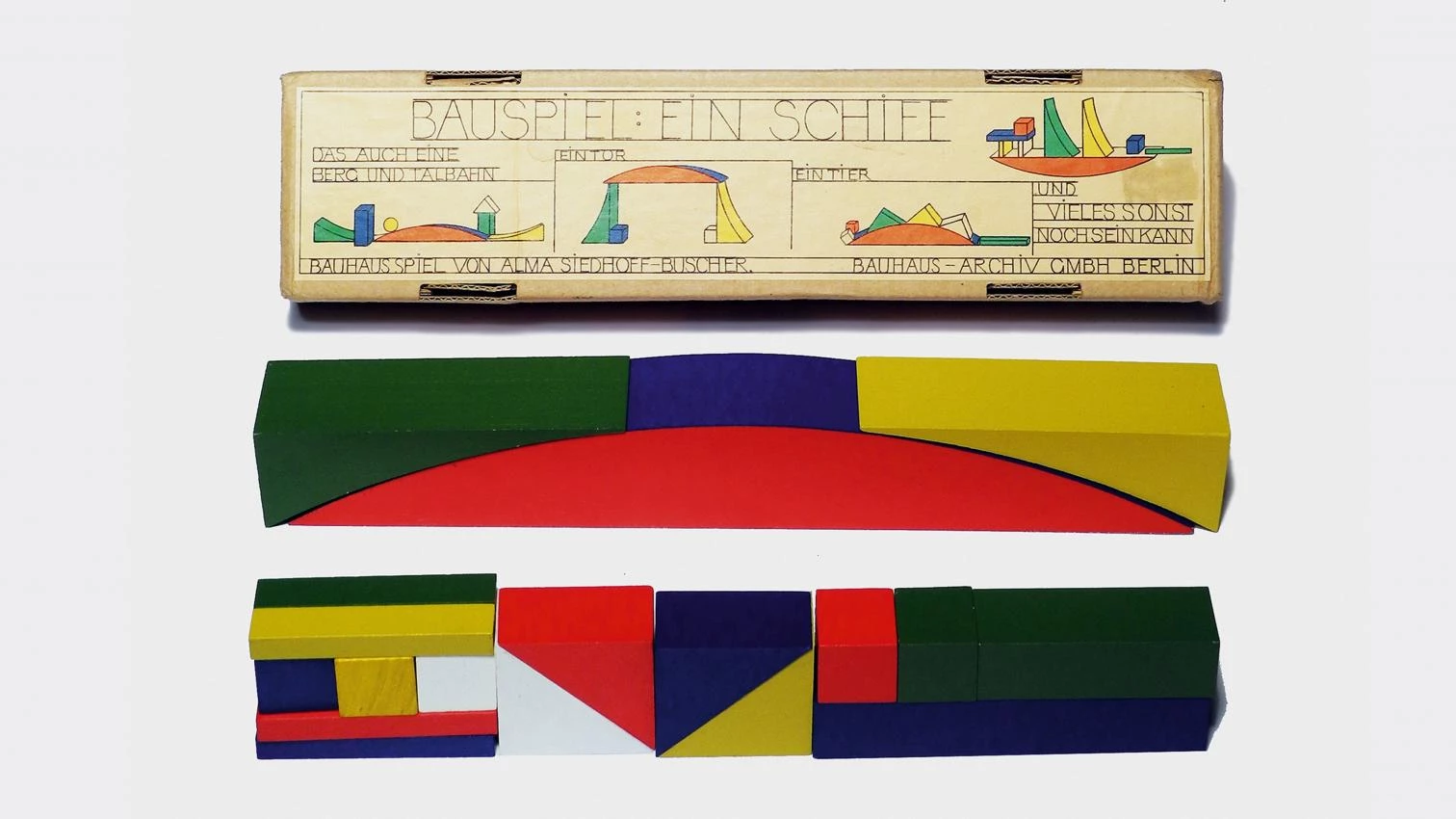

As for construction toys, specifically, we can mention Historia de los juguetes de construcción. Escuela de la arquitectura moderna (Madrid, 2012), a work of Juan Bordes, the sculptor, architect, professor, collector, and art historian and theorist who addressed the theme in La infancia de las vanguardias. Sus profesores desde Rousseau a la Bauhaus (2007), which analyzed the educational reforms carried out by the pedagogy of 18th-century Enlightenment. The exhibition on view at the Círculo de Bellas Artes in Madrid, titled ‘Juguetes de construcción. Escuela de la Arquitectura moderna,’ is the result of more than twenty years of acquisitions from the international market. The rareness of the pieces is impressive; all are of the kind that, after a bout of intensive use, end up in the attic or garbage.

Parallel to the exhibitions we remember the controversial art/childhood matter. The archaeologist Corrado Ricci, who wrote L’arte dei bambini (Bologna, 1887), was first to suggest that children’s scribbles and doodles could be considered artworks. His work has been published in Spanish with a revision by the gallerist Antonio Machón, author of Por qué dibujan los niños: Guía práctica para padres and maestros (Madrid, 2015). Aside from the psychologist/epistemologist Jean Piaget’s insightful studies on the learning process and cognitive development of children, there is a whole body of literature on the theme. We can mention the tract by the painters Ramón Cascado and Antonio Aznar, Nuestra manera de ver. Experiencias plásticas con experiencias con el papel. Una contribución a la didáctica del arte (Madrid, 2015), which addresses the serious nature of origami, the art of folding paper which Unamuno practiced and which the pedagogue Friedrich Froebel (1772-1852), creator of the first kindergarten and disseminator of building blocks for use in nurseries, considered “an efficient tool for the development of the child in school.”

Construction Sets

Geometrical recreations have always been good for making the mind moreagile and increasing figurative imagination. Stomaquion, a Greek game believed to have been invented by Archimedes, is similar to Tangram, which in 1815 an American shipping captain purchased in Canton, with its book of instructions. With this ‘Chinese puzzle’ consisting of five triangles, a square, and a rhomboid which together form a larger square, one can make thousands of silhouettes of persons, animals, buildings, and more. In the West, combinatory art, linked to Euclidean geometry, always preferred three-dimensional figures. In the 17th century, construction sets were wooden blocks with painted architectures. Luxury items for aristocratic children, as with the house of cards and the paper cut-out, its archetypes were collapsible models. In the 19th century, with the democratization of education, the classical building blocks took on didactic value. Just as a future artist or artisan had to learn to draw, in the liberal schools – from Pestalozzi (1746-1827) to Maria Montessori (1870-1952) by way of Froebel, manual works, and problem-solving exercises – the creative spirit inherent in the human being since childhood had to be awakened.

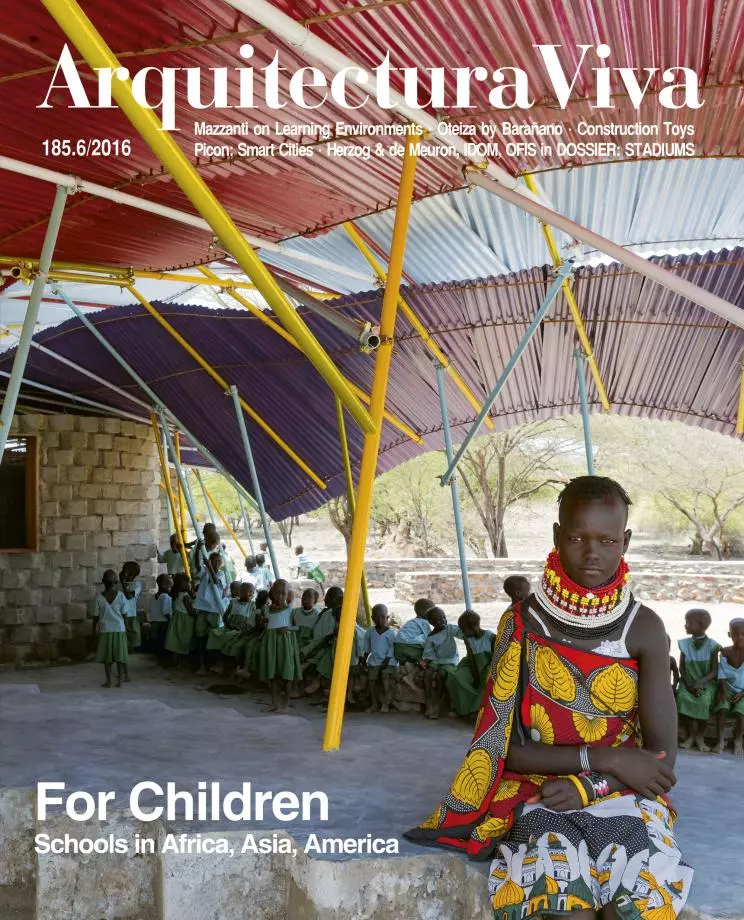

Inspired in construction sets, the montage of the exhibition is the work of the designer Enrique Bordes, the collector’s son faithfully interpreting paternal ideas. In accordance with the Vitruvian triad Firmitas/Utilitas/ Venustas, the most unique objects are placed in rectangular vitrines, following a chronological and conceptual order. As a text on the wall of the first room says, the exhibition is not due to any nostalgia for childhood. Yes to the germinal role of architecture. In each of the showcases, each box shows the pieces with the corresponding instruction manual, which, illustrated with planes of models, is in itself a concise and synthetic treatise on construction.

Since the mid-19th century game boxes have always had an attractive lid or cover with the familiar picture of a child making a building, alone or with a sibling, complacent parents looking on. Inside each box, the pieces slick with bright, nuance-less primary colors are arranged in perfect order. The latest construction toy sets, consisting of rods, hinges, and bolts, are sold in cylindrical cans. The boxes come in a variety of materials: solid wood, baked clay, artificial stone, plexiglass metal, and plastics. The cubes, cylinders, and other polyhedrons, just like the pieces that already come in classical orders like arches, pinnacles, or domes, serve as elements of imaginary constructions. In accordance with evolution in art and in modern construction techniques, the models follow stylistic changes, developing from neoclassicism to historicism, from eclecticism to modernism, and from expressionism to rationalism, to end with Fuller’s geodesy, Archigram’s fantasia, and other icons of postmodernity. Besides constructing buildings and works of engineering – such as bridges and the Eiffel Tower – by joining different pieces one can recreate entire urban ensembles in a virtual reality.

Until the mid-19th century, the cubic pieces were held up through weight balancing. But the stability was precarious. Then, thanks to an accidental discovery of an American manufacturer of cricket games as he watched his children play with the remains of the jagged packaging of his products, the cubic pieces were made to interlock. Grandall Blocks caused a change in the method of constructing with solid components. The famous Meccano and Lego sets, made of metal and plastic, respectively, use different techniques of holding pieces in place. In his exhibition Juan Bordes clearly marks the divisions in the historical times of construction game sets, which in spite of Internet and the virtual world of computers are still very much alive.

Models of Architecture

Construction toy sets have always been linked to the concept of an ideal architecture. Froebel’s didactic program was determinant in the training of Le Corbusier and Gropius. So had it been, previously, for Frank Lloyd Wright, whose mother, a schoolteacher advocate of kindergartens, bought him such a set when he was a little boy.

Let us also remember Bruno Taut, who published Die Stadtkrone (The City Crown) in 1919, the same year he designed a set of pieces of colored glass that summed up in miniature form his Alpine notion of architecture. And neither should we forget that Malevich created suprematist models which, though not construction toys, had close ties with those sets, nor that the sculptor Anthony Caro recreated their evocative forms in his ‘Arena Pieces.’

For Roland Barthes, as expressed in Mythologies (Paris, 1957), children’s toys of his time were a microcosmos or homunculus version of adult consumer society. The semiologist denounced gentrification and the banality of fashion, and the only toys he spared from criticism were construction toys, which promoted bricolage and made children creators. Against toys he said were ‘chemical,’ Barthes yearned for the old toys made of wood, a living material, familiar and poetic, not like the inert mass of artificial products.

In the final analysis, the exhibition confirms that toys are not always just the puerile objects that experts of the Ancien Régime held them to be, as defined by Covarrubias in Tesoro de la Lengua Castellana (1611): “something childish and of little importance.”