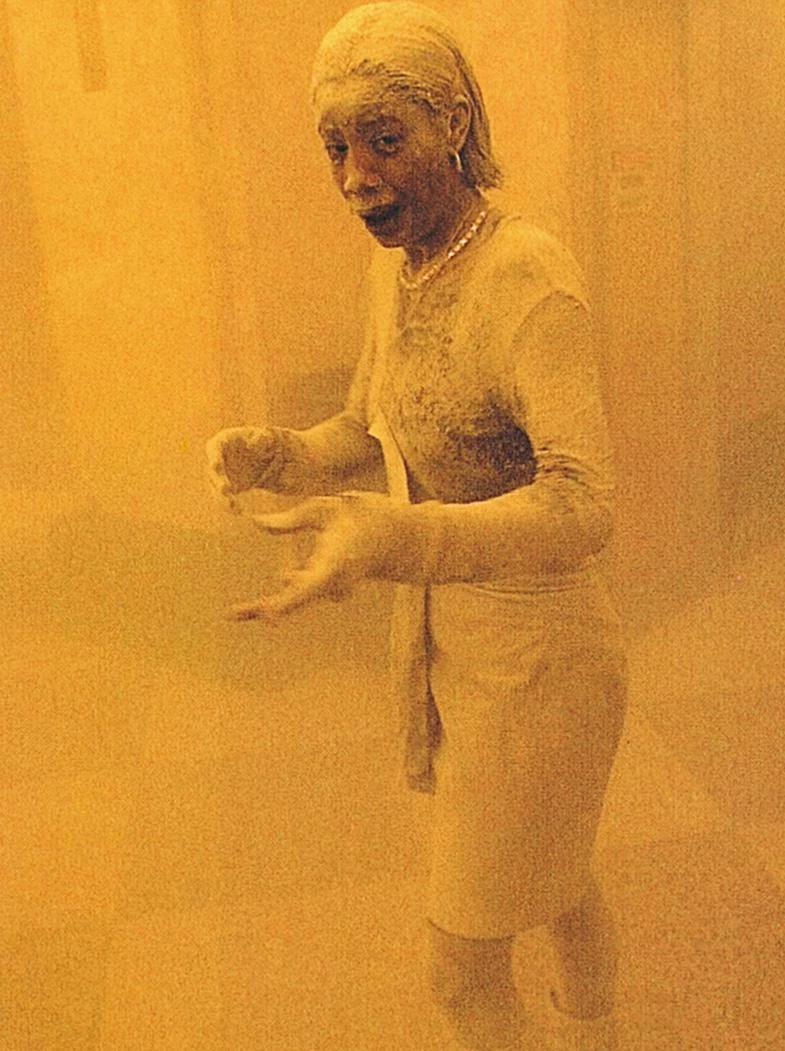

We live in a glass park. If the 20th century can be summed up in the skyscraper and the airplane, the fragility of the 21st is encapsulated in their tragic encounter of 11 September. But the perverse double fusion of Boeing brothers and Twin Towers does not only throw light on the dangers of a flying lake of kerosene or an interminable shaft of steel and concrete: it violently bares the fiasco of human domestication. After the ideological and territorial clashes of the century past, this is neither a Huntington-style conflict of cultures, nor a Pearl Harbor of impeccable geostrategic legibility, nor an unexpected Challenger or a haphazard Chernobyl illustrating the vulnerability of technical reason. What the blurred, anonymous, and lethal terrorism of Manhattan’s Black Tuesday reveals is the derailment of the civilizing process, the regressive mutation of the tamed animal into a psychotic one, and the need of our human park for the renewed discipline demanded by the philosopher Peter Sloterdijk.

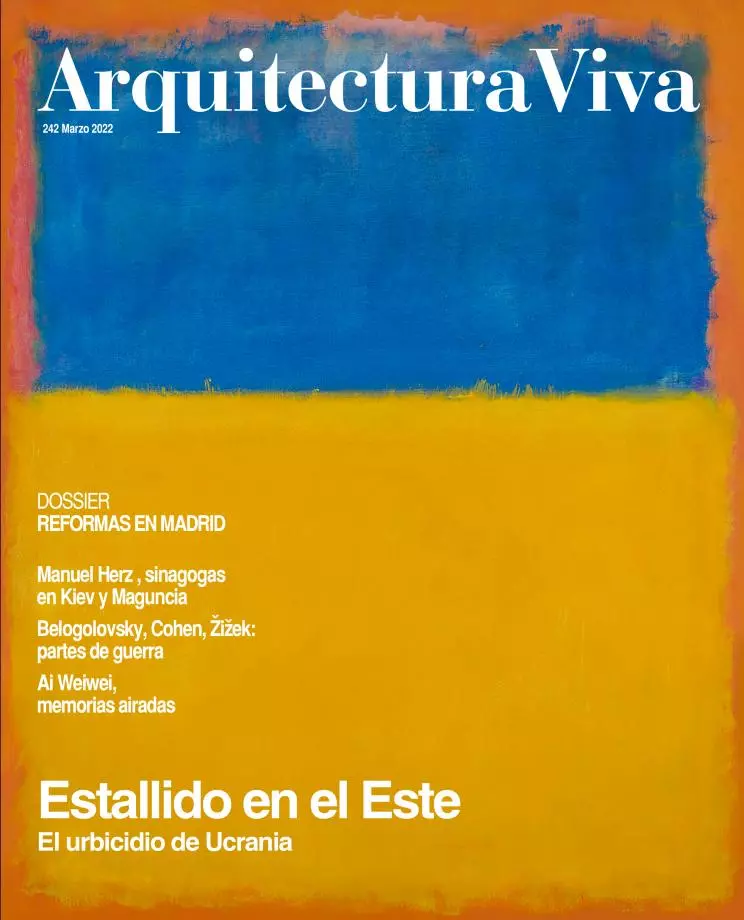

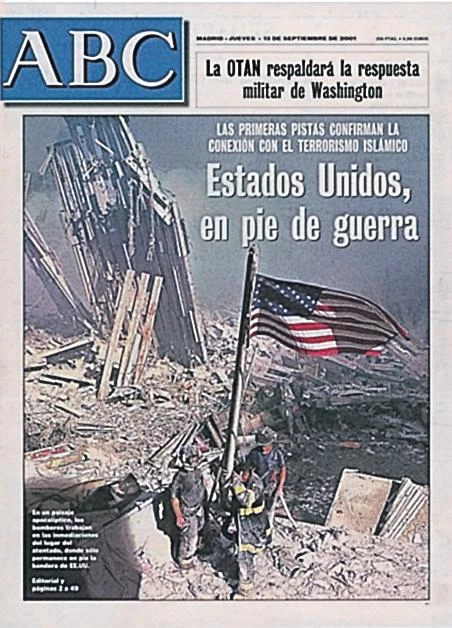

In the world to come, we will trade liberty for security. Beyond the inevitable transformation of commercial aviation, the probable decline of high-rise construction, or the expectable hysteria with regard to the Islamic universe that the novel by the French writer Michel Houellebecq’s Plate-forme forebodingly feeds, the orderly regulation of everyday life will reach a point of inflection in the vertiginous heyday of an individualism turned dysfunctional. In the face of a homicidal and suicidal visionary who believes himself a paradoxical David hitting a pentagonal Goliath, or a Samson bringing down the columns of the temple of capital, perhaps less freedom is the only way to defend freedom, and the voluntary submission to the collective discipline of democracy is the best way to protect the individual, as the wounded serenity of the American reaction has manifested. The towering inferno is not an image of a humiliated USA, but that of the assaulted human race, and it exposes not so much a leak in civil or military security as it does a crack in the education ataming of our species. In the requiem of these skyscrapers, the bells toll for us.

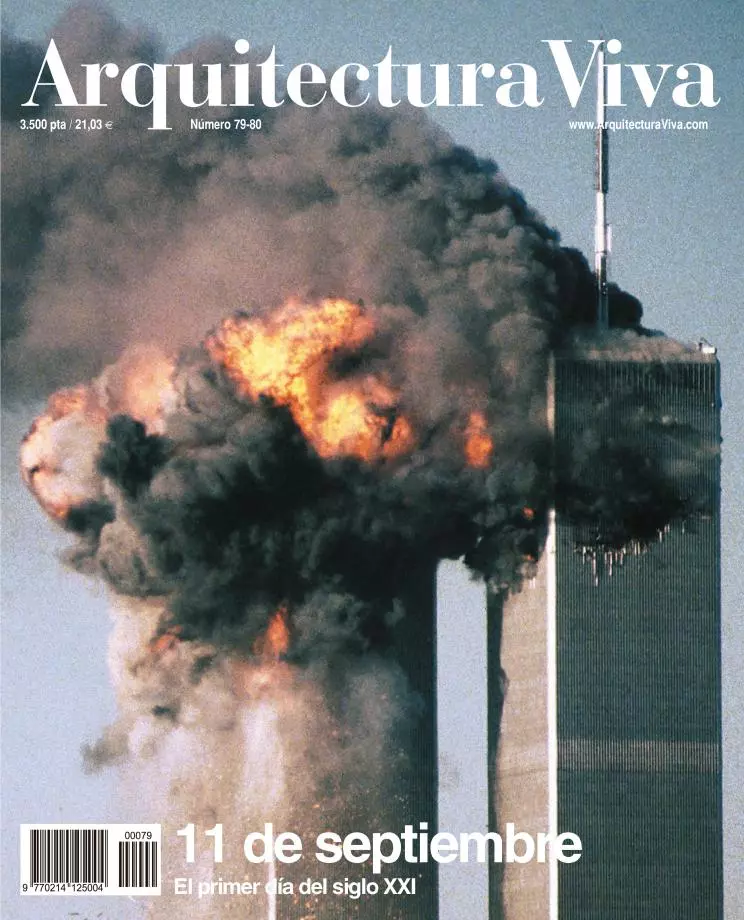

If the 20th century closed on 9 November 1989, with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War, the 21st began on 11 September 2001, with the terrorist attack that destroyed the Twin Towers of New York.

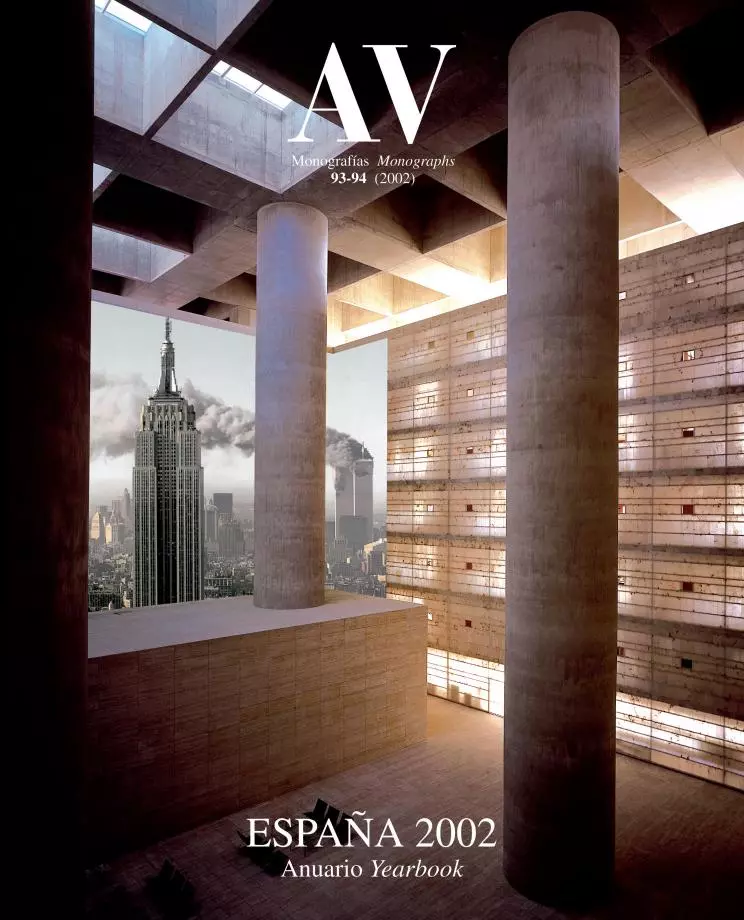

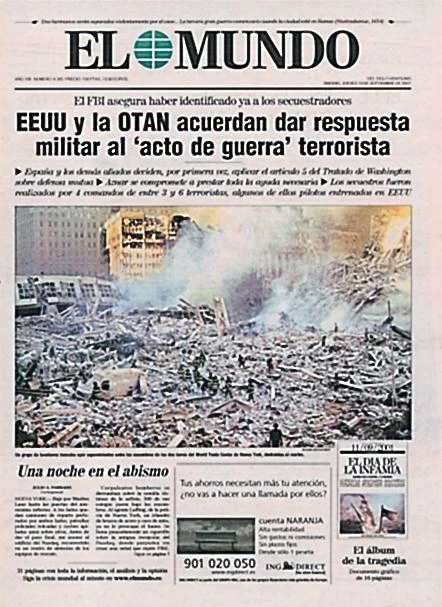

For this precise historical moment, New York’s Twin Towers provide such a perfect motif as to seem almost unreal. In the financial heart of Manhattan, the buildings designed by Minoru Yamasaki for the World Trade Center, which for a while were the planet’s tallest, were the very embodiment of corporate power and a globalized economy. Although we still find it hard to believe that those icons have altogether vanished from the city’s skyline, the apocalyptic images of a New York where mass panic has given way to the dusty silence of recent ruins forces us to accept that, if the 20th century ended on 9 November 1989 with the fall of the Berlin wall and the termination of the Cold War, the 21st century began on 11 September 2001 with the cruel and devastating staging of the vulnerability of the core of that economic and military empire that Muslim terrorists single out as the Great Satan, even if the demolished landmarks were only nodes of a resistant and diffuse network spread all over the globe. Exactly during the long decade of twilight between these milestone dates developed an architectural project that struggled with the guilt-ridden memory of the most heinous episode of a century rich in evilness: the Jewish Museum of Berlin, conceived shortly before the wall went down and inaugurated, so it happens, on the eve of the day of America’s horror.

The burning colossus is not the image of a humiliated America, but of humanity attacked, and it reveals not so much the failure of civil or military security as the breakdown of the educational taming of an unruly species.The blurred, anonymous and lethal terrorism of Manhattan’s black Tuesday evidences the derailing of the civilizing process, the regressive mutation of the domestic animal into a psychotic one.

Designed by Daniel Libeskind, an American Jew of Polish origins who gave it the zigzagging form of a geometrical ray of lightning, and directed by Michael Blumenthal, an American Jew of German stock –Treasure Secretary under Jimmy Carter – who softened the building’s angular image so as to present it as a conciliatory institution, the museum opened in conspicuous simultaneity to the destruction of the Twin Towers, offering a complementary symbol for contemporary disorder. While the robust Cartesian rationality of the World Trade Center lies hidden in rubble, ash, and smoke in south Manhattan, the broken, lyrical emotion of the Jewish Museum presents itself in Berlin as a shaken sign of the inhuman tremor of our times. Against the mad, infamous violence of the New York hecatomb, a dramatic and pedagogical testimony to the Jewish holocaust; and against the catastrophic devastation of forms and lives, the rhythmical, musical ritualization of fractures, as in a protective and healing exorcism.

One of the WTC towers on September 11

Also in Berlin, Peter Eisenman is building the Holocaust Memorial, a huge plaza occupied by an orderly labyrinth of concrete blocks, at once ominous and placid, which shudder to a quiet wind. But now the architect sits in his Manhattan studio, contemplating the tufts of smoke rising from the southern tip of the island, and not even the immediate friendly call from Manuel Fraga, his client in Galicia’s City of Culture, manages to snap him out of the stupor. “The towers were a symbol of capitalism.This is worse than Pearl Harbor.” His wife Cynthia weeps inconsolably, as consultants stranded by the cancelling of flights look for a place to sleep. The architectural journalist Cathy Ho, who heard the roar of the first plane over her building, describes the chaos of sirens and terrified multitudes she sees through the window, and takes it upon herself to provide the essentials for the colleagues trapped on the island. She would have liked to donate blood, as Laura Bush and Yassir Arafat were to later, for the invisible wounded of a calamity that only leaves dead and survivors. But in Central Park on Saturday, after a trivial argument over a football, a woman had bitten her savagely and she had to be given tetanus and hepatitis B shots, besides a prescription for antibiotics. Definitely the human park needs taming anew, lest this species never survive in the dark glass jungle that is now our habitat.