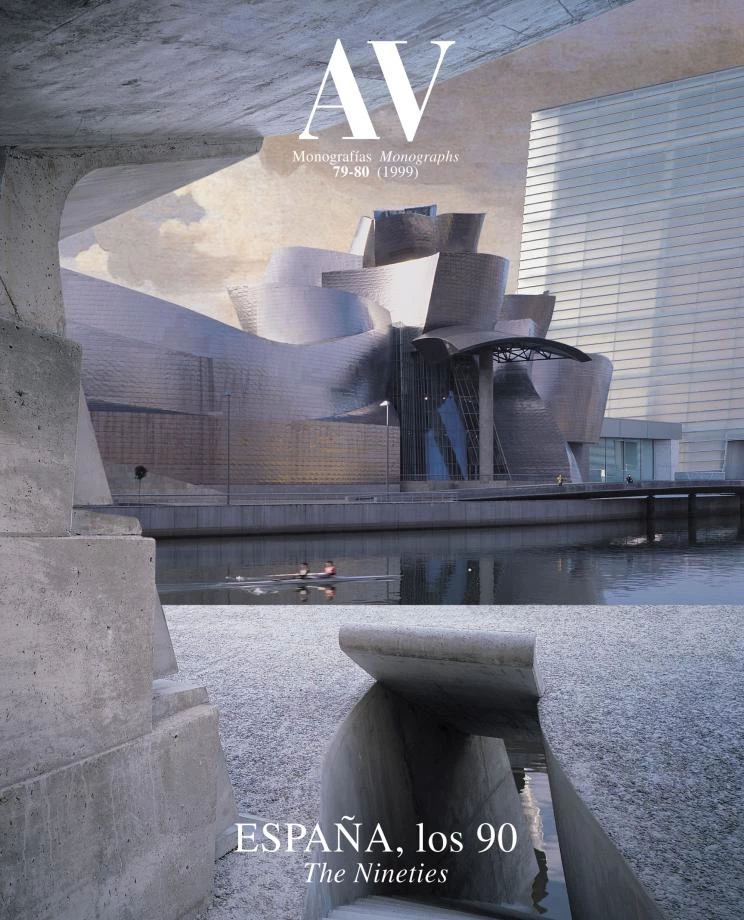

Opera of the Orient

The simultaneous completion of the Teatro Real and the Plaza de Oriente reflects the conservative mood of the Spanish capital.

Madrid has two new horseshoes: a horseshoe of red velvet seat boxes and a horseshoe of underground parking lots. Tangent to one another at their curved ends and connected by ramps and columns, they occupy the historic and symbolic center of the city, with the Bourbon palace rising nearby on the site of the old fortress. The theater horseshoe is the heart of Madrid’s restored opera house, which served as such from 1850 to 1925 but was transformed after various vicissitudes into a concert hall, and was used for that purpose from 1966 to 1988, when the works now being culminated began. In turn, three parking levels form a horseshoe beneath the Plaza de Oriente, which was brutally excavated to bury traffic and link the Royal Palace and the Almudena Cathedral by foot, via a pedestrian esplanade, to the revived Royal Theater. Though nurtured by different administrations – the theater was boosted by successive culture ministries during the socialist years, while the plaza is an emblematic realization of the current conservative city hall – both projects were characterized by huge budgets, huge delays and huge controversies. Their simultaneous completion enables us to gauge Madrid’s current tastes and to illustrate the paradoxes of urban and cultural policies.

Undertaken by administrations of opposed political signs, both the Teatro Real and the Plaza de Oriente renovations have been high-budget operations characterized by delays and controversies.

Anyone reckoning in 1982 that the two great socialist works in the historic heart of the country’s capital would be a cathedral and an opera house would have been considered insane. And the very idea that the conservatives would be the less respectful toward the city’s monumental heritage would have seemed highly implausible. But this is exactly what has happened in the past fifteen years. The cultural policy of the socialists was traditional to the point of allocating public funds to the completion of a cathedral initiated by the Marquis of Cubas a century before, in 1879, in the euphoria of Catholic affirmation that followed the first Vatican Council, and sticking to the project drawn up at the height of the Spanish postwar period, in 1944, by the architect Fernando Chueca, who supervised the work until its completion in 1992. And the socialists were so conservative as to promote, at huge cost, the restoration of an operatic tradition that had been interrupted for 60 years, using the very same building, designed in 1818 by Antonio López Aguado, where this socio-musical activity had had its past splendor; a building which was remodeled by José Manuel Gonzalez Valcárcel, the same architect who had transformed it into a concert hall in 1966, and who now supervised the construction of the reborn opera house until his dramatic death in 1992, right on the site of the works.

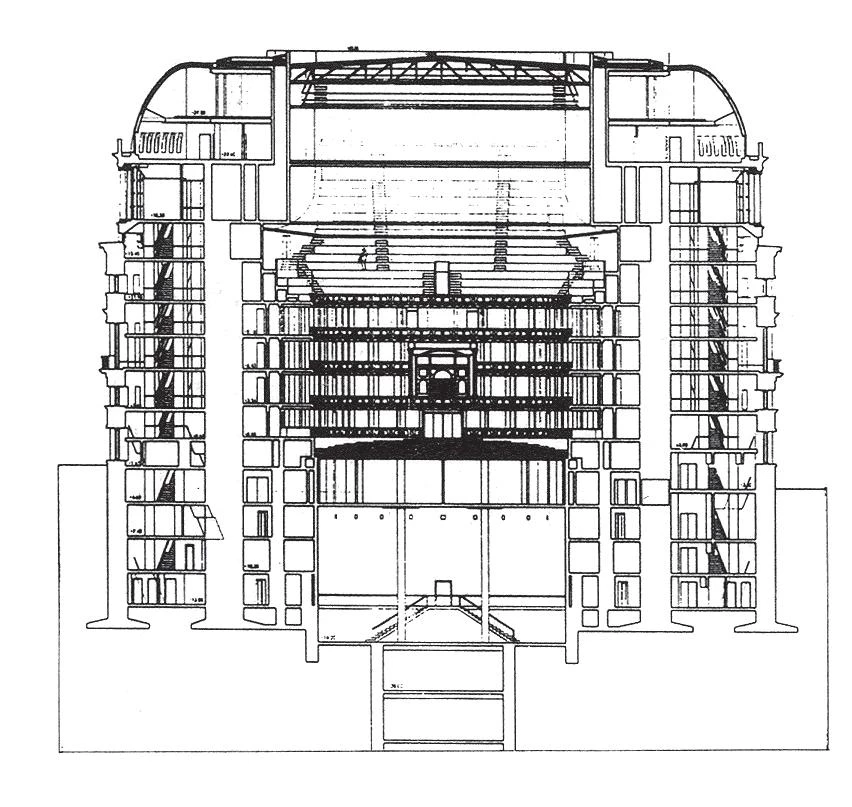

Francisco Partearroyo assumed the principal role in the Teatro Real renovation – originally planned by Antonio López Aguado in 1898 – following the dramatic death of the architect Valcárcel in 1992.

The urban policy of the conservatives, in turn, who have for quite some time now had Madrid’s city hall as a testing laboratory and figurehead, has been so extraordinarily contemptuous of the city’s traditional scheme as to have no qualms about disemboweling streets and squares in favor of tunnels and underground parking lots, so meanly subordinated to the totemic cult of the automobile as to sacrifice any patrimonial value on its heathen altar, and so embarrassingly uncultured as to bring its usual devastation of the subsoil and folkloric decoration of the surface to the very heart of the city, the environs of the fortress from which Madrid’s medieval core grew into successive precincts along the cornice of the Manzanares River. And in this symbolic and geographical center, the conservatives have been so shamelessly stubborn as to ignore public opinion and fabricate a tacky esplanade for a theme park of the Bourbon monarchy.

Theater and Square

The very conservative cultural policy of the socialists and the very subversive urban policy of the conservatives have converged in the simultaneous termination of the Teatro Real and the Plaza de Oriente, officially inaugurated on two successive dates in October. Though true that the party in power has opened the Teatro Real as a thing of its own and tinged the ceremony with conservative Spanishness, though true, too, that the timing of the Plaza de Oriente ribbon-cutting has been hastened in order to coincide with the inauguration of the theater, with its underground parking still unready for use, these circumstantial anecdotes do not affect the paradoxical, underlying concord of the two operations with a conservative taste that has taken root in Madrid more than we dare to admit. In fact it would not be absurd to think that the criticisms most frequently leveled at the works would have been avoided if the respective architects had refrained from modern follies and stuck instead to the strictest papier- mâché historicism.

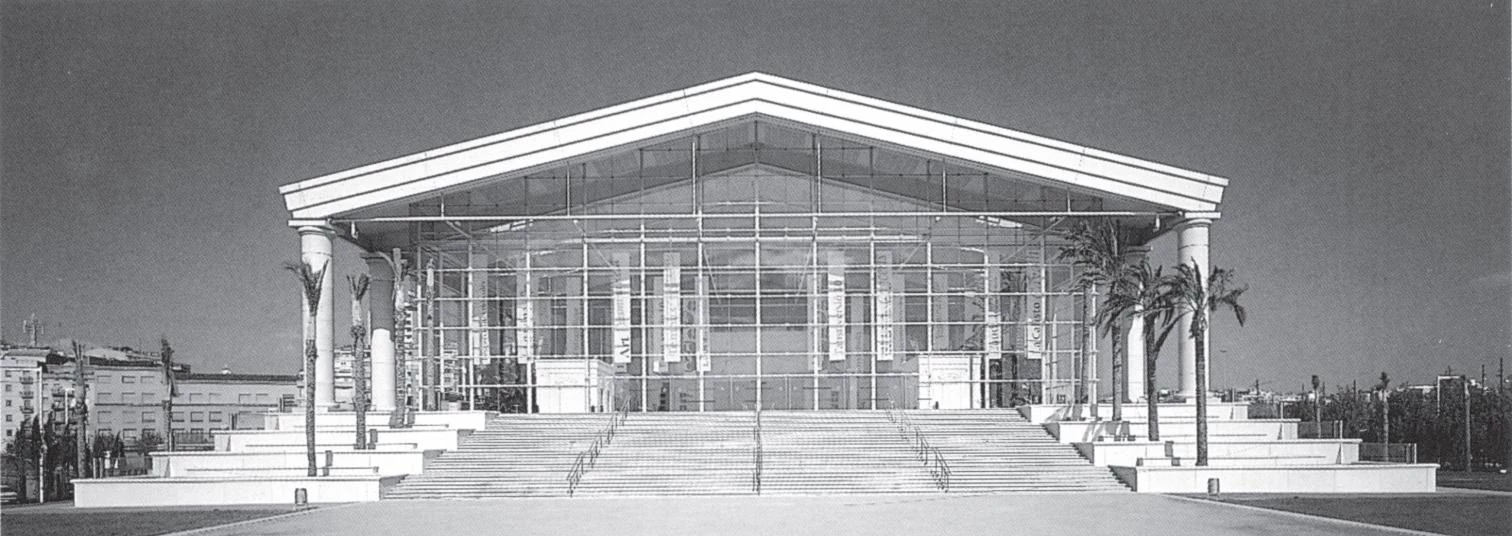

With the reconstruction of the Liceo (below), by Ignasi de Solà-Morales, and the National Theater of Catalonia (above), by Ricardo Bofill, Barcelona takes part in the recent design of major projects for the performing arts.

In any case, the works equally bespeak the personality of their authors, Francisco Partearroyo and Miguel Oriol, two competent professionals who share an unrequited love for architecture. Partearroyo, who assumed the essential part of the Royal Theater commission on the death of Valcárcel, had drawn up a project for the enlargement of the Prado Museum long before the ill-fated competition was convoked, and transformed some old military barracks into a campus for the Universidad Carlos III, two interventions on historical buildings where he displayed more organizational capacity than visual refinement. In the Royal Theater, his postmodern classicism is halfway between the rhetorical classicism of Ricardo Bofill’s National Theater of Catalonia and the mimetic academicism of Ignasi de Solà-Morales’ Liceo, Spain’s other two major performing arts projects, and suffers from a lack of sensibility in its interior design, which contrasts with the architect’s proven managerial expertise.

Oriol, in turn, who is responsible for the Plaza de Oriente in more than one sense, since besides being the architect of its refurbishing he conceived and doggedly promoted the idea for almost two decades, has amalgamated several obsessions in this personal project of his: the separation into different levels of pedestrian and vehicular traffic, an outmoded urban concept that corresponds to his formative years, and which he is threatening to apply as well to the Paseo del Prado; the combination of classicism and technology, with the results that can be seen in the Euroforum at El Escorial and in the hapless elevator temples of the plaza; and the narrative folklorism that is perhaps a fruit of his literary tastes, manifested here in the heterogeneous variety of paving materials, such as multi-colored granite, marble, slate and pebbles forming unrelenting bands, patterns and chessboards on the interminable surface of the square, which is then further adorned with steps and plinths and a whole range of other intricate episodes. And the worst is yet to come: a crowd of monarchs, on foot and horseback, to give the square the figurative Bourbon stamp it apparently lacks, which Madrid’s incumbent city hall, knowing its penchant for civic statuary, will surely not take long to supply, thereby imposing its indispensable comic ending on this Plaza de Oriente where Pilar Miró will no longer film Prince Philip’s wedding.

The late Alejandro de la Sota used to say that an auditorium must be judged with closed eyes, so perhaps we should appreciate the Teatro Real in this manner, attentive to the music and the feel of velvet, and maybe we ought to sense the plaza like this as well, shutting our eyelids and opening the nostrils to the disquieting perfume of the hedges that have been saved from being colonized by the automobile and the thematic tourism of memory. That sound, that touch and that aroma might rescue us from the trauma of the gaze that contemplates and censures, and raise hopes that the two inevitable horseshoes will at least bring good luck.