Yi Sang, Korean literature’s perpetual enfant terrible, was not only a cutting-edge writer but a working architect, and his oeuvre teems with dark rooms, mirror worlds, and other uncanny spaces.

Bong Joon Ho’s film Parasite (2019) unfolds in two of the most memorable domestic spaces in recent cinema: the Kim family’s squalid apartment, on a Seoul street prone to fumigation and floods, and the tech entrepreneur Nathan Park’s sleek modernist mansion, which the grifting Kims infiltrate. In a delirious twist halfway through the movie, Bong reveals that the Park home, like similar structures built within living memory of the Korean War, has a “secret [bunker] where you can hide in case North Korea attacks or creditors break in.” (Neither Communists nor capitalists can be trusted.) Parasite imagines contemporary Korea as a haunted house, where rigid lines—between haves and have-nots, the present and the past—are broken in shocking fashion.

The mansion was designed and originally inhabited by a world-famous architect, Namgoong, who left Korea after the place was sold to the Parks some years earlier. The fictional Namgoong perhaps figures as Bong’s alter ego: the absent, godlike designer of the drama and chaos unfolding on-screen. Parasite and its structures came forcefully to mind recently as I read a new English-language collection of work by Yi Sang, Korean literature’s perpetual enfant terrible. Yi Sang was not only a cutting-edge writer but a working architect, and his oeuvre teems with dark rooms, mirror worlds, and other uncanny spaces.

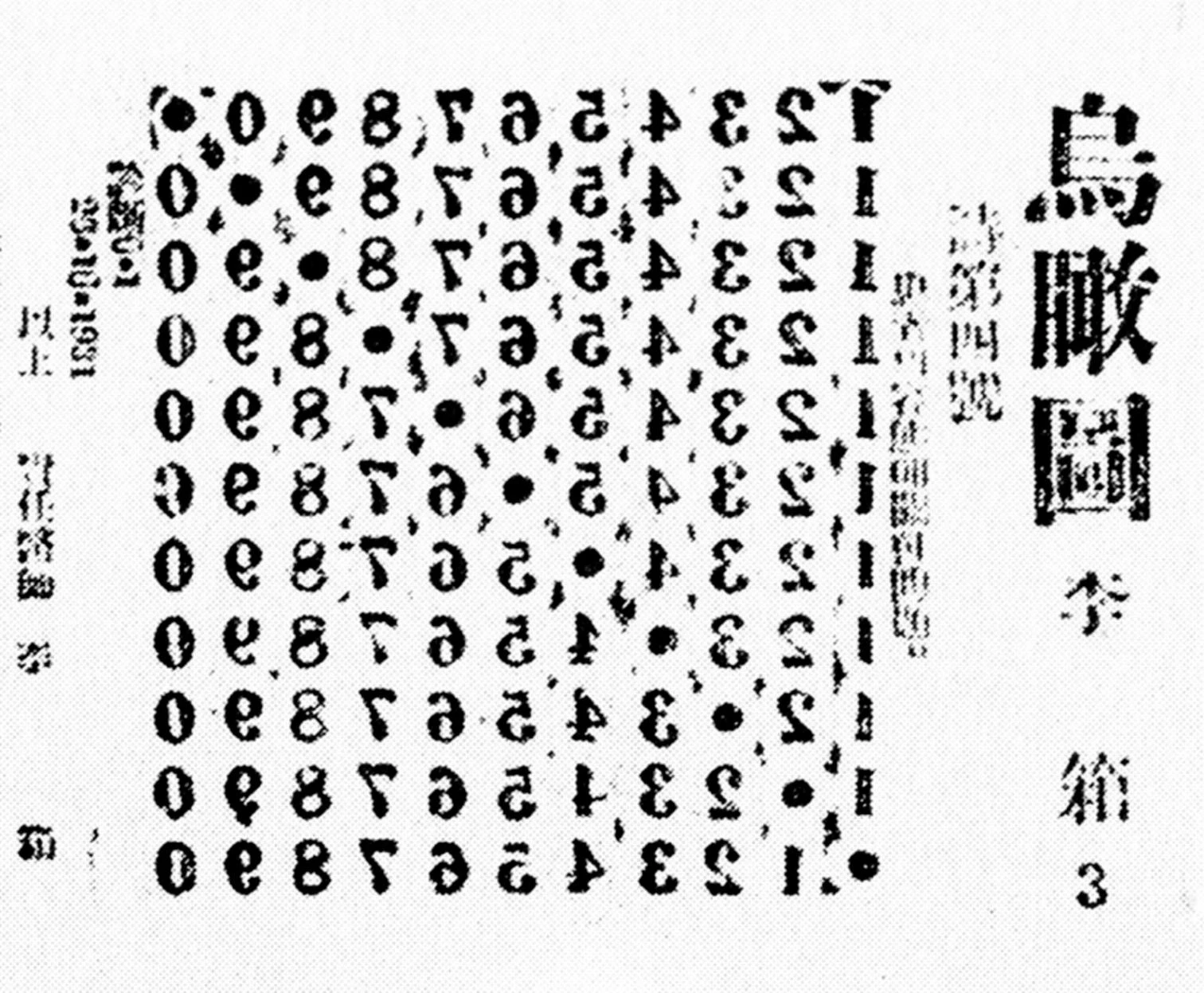

In 1929, at age nineteen, Yi Sang won a contest to design the cover of a magazine for Japanese architects in Korea. Two years later, his first poetic sequences appeared in that publication, with industry-appropriate titles like “Solid Angle Blueprint” and “Bird’s Eye View.” The poem “Movement” suggests Gertrude Stein vanishing into an Escher print:

I climb up above the first floor to the second floor to the third floor to the rooftop garden and look to the south and there is nothing there and look to the north and there is nothing there and so I go down from the rooftop garden to the third floor to the second floor to the first floor…

Still others use the language of geometry and physics—grids, equations, an “azimuthal study of numbers,” even actual shapes—to disorienting effect. Logical statements collapse into nonsense or sorcery. The mostly mathematical “Memorandum on the Line 3” ends with a glimpse of the reader’s blown mind: “The brain opened into a circle like a folding fan, then rotated completely.”...

The New York Review of Books: A Poet’s-Eye View