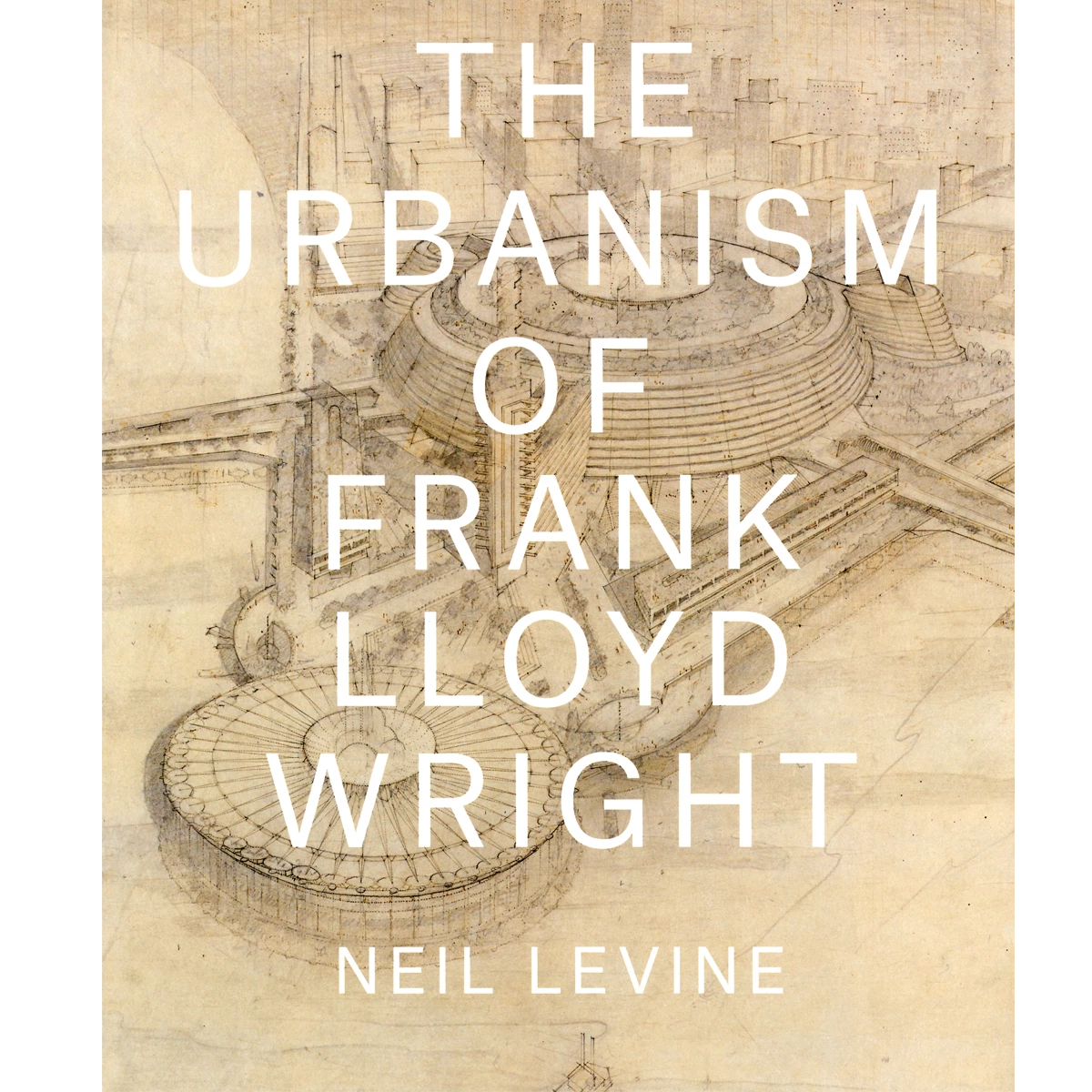

If there is a quintessentially anti-urban master, it is Frank Lloyd Wright. After all, his great urbanistic utopia is Broadacre, which he published under the title The Disappearing City, and his militant ruralism has been indistinctly associated with Jefferson’s gentleman farmer, Emerson’s return to nature, or Olmsted’s picturesque gardens. But the Harvard historian Neil Levine has put forward a rectification of this conventional idea through a monumental work, the product of twenty years of study and the first book ever to benefit from the new digital photography of Wright’s drawings, carried out after the transfer of the archives from Taliesin West to Avery Library, their new home thanks to a project developed in collaboration with MoMA. It was this institution that did a first stocktaking of Wright’s oeuvre with its exhibition of 1940, revised thirty years after the architect’s death with the major exhibition of 1994, which was more significant than the one held at the Guggenheim in 2009. Levine had published his Wright monograph in 1996, and contributed to the Guggenheim catalog with an article, ‘Making Community Out of the Grid,’ which presented the themes he would address exhaustively in The Urbanism of Frank Lloyd Wright: a title which, as he points out, seems oxymoronic, precisely because it signals a radical revision of Wright’s work, against the grain of the historiographic canon, presenting him as a profoundly urban architect; a book, in the final analysis, so ambitious intellectually and so painstaking in its erudition that it is bound to become a critical milestone with the importance of the MoMA exhibitions of 1940 and 1994.

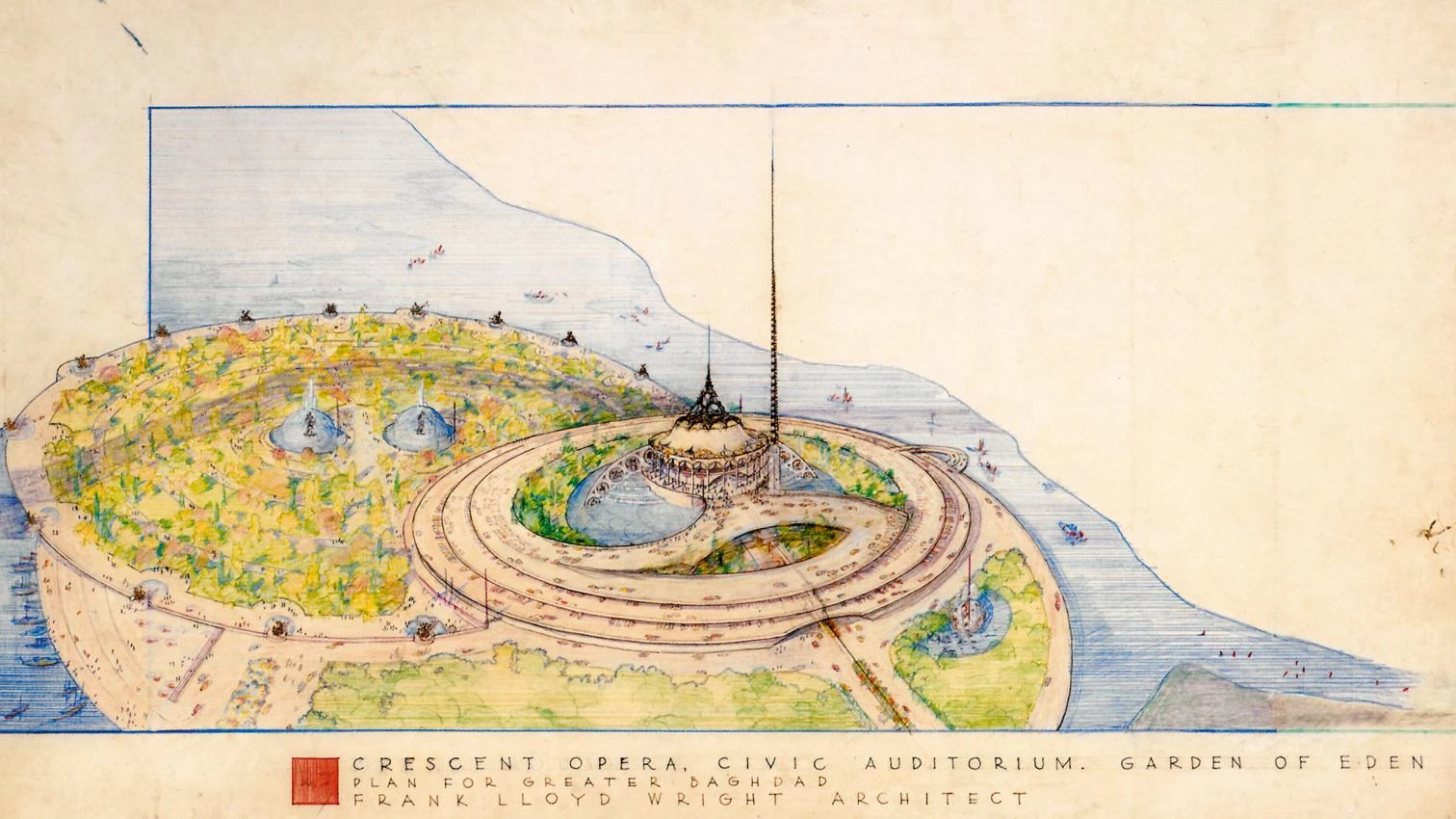

The first of its three parts looks at ‘the new streetcar city,’ and develops his text of 2009, where he subordinated the Prairie Houses to the Midwestern grid as a symbol of democratic egalitarianism, and more specifically the insertion of these houses in grouping schemes, especially the Quadruple Block Plan. The second part is about Broadacre, which put the city into question at the dawn of the automobile age, and which Levine considers “more an anomaly than representative of Wright’s architecture as a whole,” explaining its gestation in 1929 as a response to Le Corbusier’s urban proposals, against the conventional view that associates it with the Crash and the Great Depression. The third and final part tackles urbanism under the hegemony of the automobile, and describes four projects in urban centers – Madison (1938), Washington, D.C. (1940), Pittsburgh (1947), and Baghdad (1957) –, which he presents in dialogue with CIAM concerns about ‘the heart of the city’ or the new monumentality of Giedion and Mumford, justifying its theatrical spectacularity in the need to create symbolic forms as a stage for mass events, and linking his rhetorical classicism to the City Beautiful and Burham’s plans for Chicago. Like the Guggenheim show, Levine’s work upholds the later operatic Wright, halfway between science fiction and Arabian Nights, and from the angle of his urban spirit: a colossal achievement that opens up vast avenues to critical discussion.