A Collective Project

The Chief Curator of Architecture and Design at New York’s MoMA explains the historical reasons behind the present surge of Spanish Architecture.

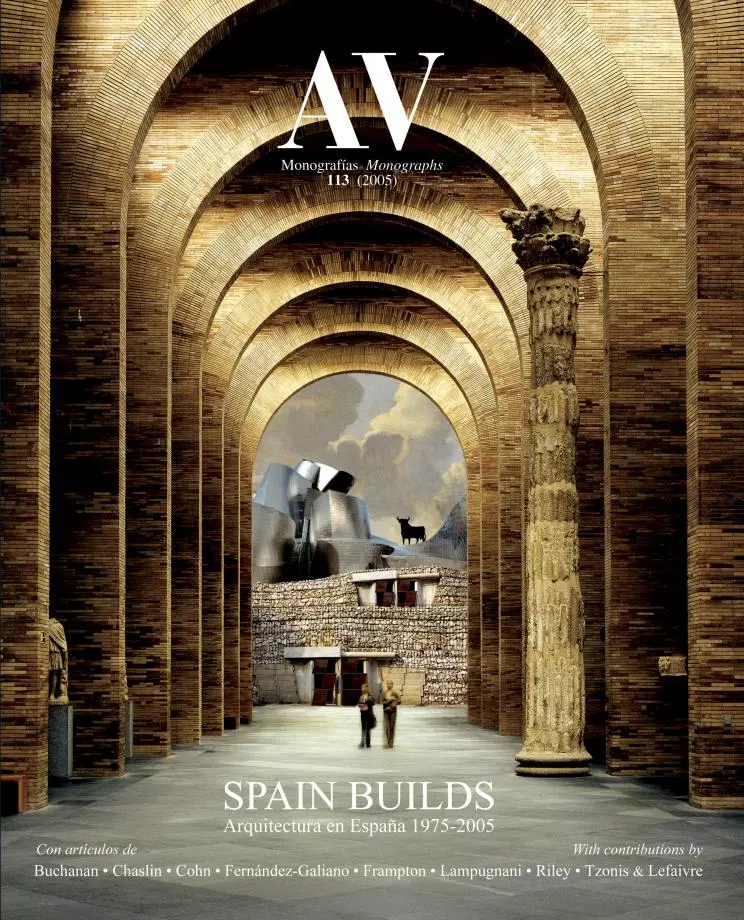

This publication is intended as a companion volume to “On-Site: New Architecture in Spain”, published by The Museum of Modern Art in New York at the time of the opening of the exhibition of the same name. Whereas that book focuses on the most recent projects in Spain’s building boom, this volume takes a more retrospective view, looking back to the dramatic unfolding of events that have transformed Spain, and no less so its architecture, since the death of Francisco Franco in 1975.

In early discussions regarding this volume, its editor Luis Fernández-Galiano and I adopted a very simple premise as a point of departure: architecture is an enterprise whose history is a mirror of the culture that supports it. In the publication’s organization this premise is readily apparent as each chapter is framed by the most significant events of the day, from the joyful establishment of a democratic constitution in 1978 to the tragedy of the Madrid Atocha station bombings in 2004.

Another premise evident in the making of this publication is the acknowledgement of Spain’s evolving role as a protagonist on a global architectural stage. Recognizing this development, the invited essayists whose writings appear in this volume all hold points-of-view developed from outside of Spain. They were selected for both their knowledge of the architectural transformation of the country over the past three decades and, equally important, for the particular prism of objectivity they might bring to the topic. Meeting for three days in Madrid last November, all of the essayists presented their work in draft form for an intense round of collegial discussion and critique, resulting in the synthetic overview you now read.

The breadth and depth of Spain’s cultural transformation is clearly evident in the parallel transformation of its architecture as documented in this volume. The expansion of civil liberties, the growth of the economy, the opening of its physical and mental borders to the world beyond have given Spain a new sense of self-definition, expressed eloquently and forcefully in the work of such figures as Rafael Moneo, Santiago Calatrava and Enric Miralles and many others. The devolution of power away from the central government has insured that the current building boom is spread across the country, reinforcing and encouraging the promotion of regional identities. Spain’s economic growth is evidently the engine behind the boom, but has many collateral benefits, not least of all the expanded possibilities offered to its younger architects. The end of Spain’s political and cultural isolation has not only created occasions for architects from abroad to work in Spain, but it has also created opportunities – well taken, it should be noted –for Spanish architects to study, work and obtain commissions on an international scale, resulting in the diverse and cosmopolitan profile of many within the profession today.

Going forward, however, the achievements of Spanish architects are not necessarily guaranteed. The appeal of Spanish architecture has often been attributed to the combination of a demanding education of architects in Polytechnical Universities where both the scientific and the artistic dimension of the profession receive due stress; unusually powerful professional associations – the ‘Colegios de Arquitectos’ – which sternly defend the legal and economic status of architects and lavishly promote architectural culture through magazines, exhibitions and events; and an archaic survival of the crafts that allows a quality in finishes and details which is rare in countries with more mechanized building industries.

Inasmuch, the schools, the ‘Colegios’ and the building industry formed a professional bridge between the cultures of the Franco period and the years of democracy. Today, however, this feeling of seamless development is altered by the rapid expansion of the educational system – in 1960 there were only two schools of architecture, Madrid and Barcelona; today there are twenty –, the weakening of the ‘Colegios’ bargaining power under European Union antitrust regulation, and the transformation of the building sector, now heavily mechanized and staffed with poorly trained labor.

Thus, the present moment offers not only an opportunity to reflect on the achievement of Spanish architects in the last thirty years but also a challenge to not only accept change but, to the extent possible, direct its course.