When it was published in 2007, A Global History of Architecture promised to be the answer to a problem present in American architecture schools. While everyone agreed that the Western architectural canon was insufficient to train young architects, there was no reliable text that could account for architectural traditions from around the world. However, the disappointment with A Global History of Architecture begins in its own table of contents, which presents 18 chronological milestones, beginning in 3500 B.C. and ending in 1950, and then lists as many as 40 topics, responding to the variety of cultures around the world, grouped under each chronological milestone. This effort to account for everything in every era makes it impossible for one to concentrate on any particular place or subject, as the texts devoted to each topic are usually only one page in length. Under the rubric of the year 1,000, for example, appear the Rajput monuments in India, the Song dynasty in China, the Fatimids in Cairo, the Almoravids in Morocco, the late Carolingian culture in Germany, the Normans, the Italian city-states, the Kievan kingdom, the Mayan Uxmal, and, finally, the Cahokia on the Mississippi. While the text is admirably unhierarchical and wonderfully documented, its organization does little to help in understanding how styles, cities and cultures develop.

The authors have given up on the idea of a coherent narrative connecting people, practitioners, techniques, and historical events, and instead have treated each topic as a self-contained piece of information, almost like an encyclopedia entry. Aside from this feeling of aimlessness, the book has the merit of being the most comprehensive and accurate handbook on world architecture. One can rely on texts that record geographical and political facts, but one cannot expect in-depth approaches to issues concerning architecture. In addition, the role of women in architecture is ignored: the book does not, for example, record the exceptional patronage of Queen Hatshepsut in the Egyptian New Empire or that of Empress Wu Zetan during the Tang dynasty in China, as well as the talent of Julia Morgan, the first woman to graduate from the École des Beaux-Arts.

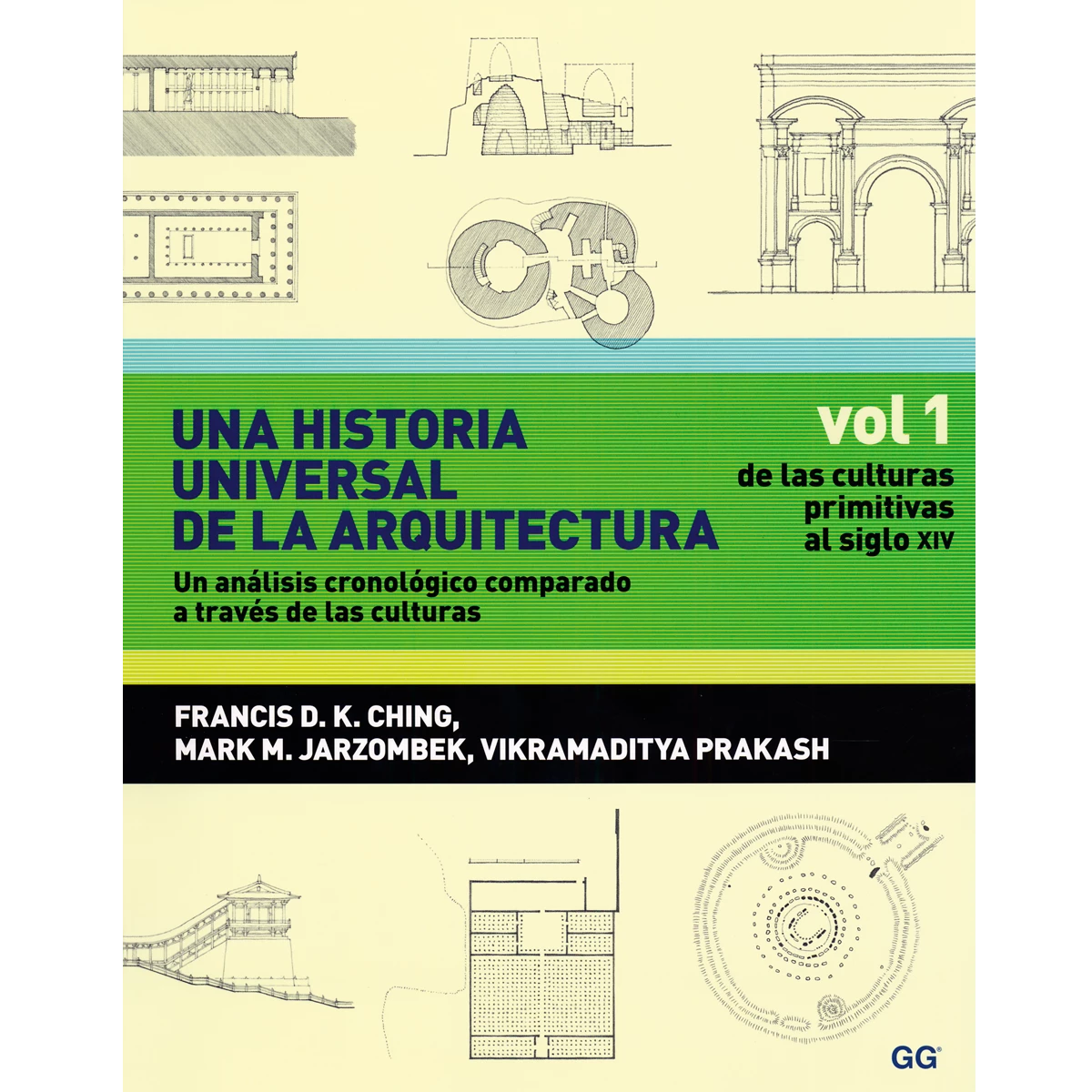

One of the book's great strengths lies in the lavish inclusion of hundreds of floor plans, sections, site plans and perspectives by Frank Ching, the man who taught the last four generations of American architects how to visualize their ideas with a pencil. However, the poor print quality makes the book uniformly gray, and its appearance, despite the array of images, is surprisingly drab.