Against Glass: the Limits of Transparency

Summer.Private intimacy and public transparency are hard to reconcile, and the information explosion of the webs create a new framework for this conflict.

We cry out for transparency while clamoring for privacy. The blurred lines between public and private, however, make it hard to address these opposed demands. On the one hand, political conflict has invaded the personal lives of elected and appointed officials, who are subjected to stern scrutiny or home harassment; on the other, more and more people are immodestly airing their private lives in the media to the guilty delight or hypocritical scandal of mass audiences. Reconciling the right of access to public information with that of protection of personal data is a juridical challenge, but also a cultural oxymoron.

We keep defending the rhetoric that the public domain should be a glass precinct, see-through for examination by the common gaze, and the private realm a hermetic fortress, armored against the intrusion of the Leviathan State. In reality, the public sphere – from legislation to diplomacy – is historically inseparable from opacity or reserve, and the private field has always been subject to an inspection that today reaches a paroxysm with the omnipresence of cameras and the full digital register of communications, contacts, or bank accounts. Maybe the time has come to realize that the ethics of responsibility authorizes penumbra, and that privacy is but a recent invention that can only be protected by knowing its inevitable limits.

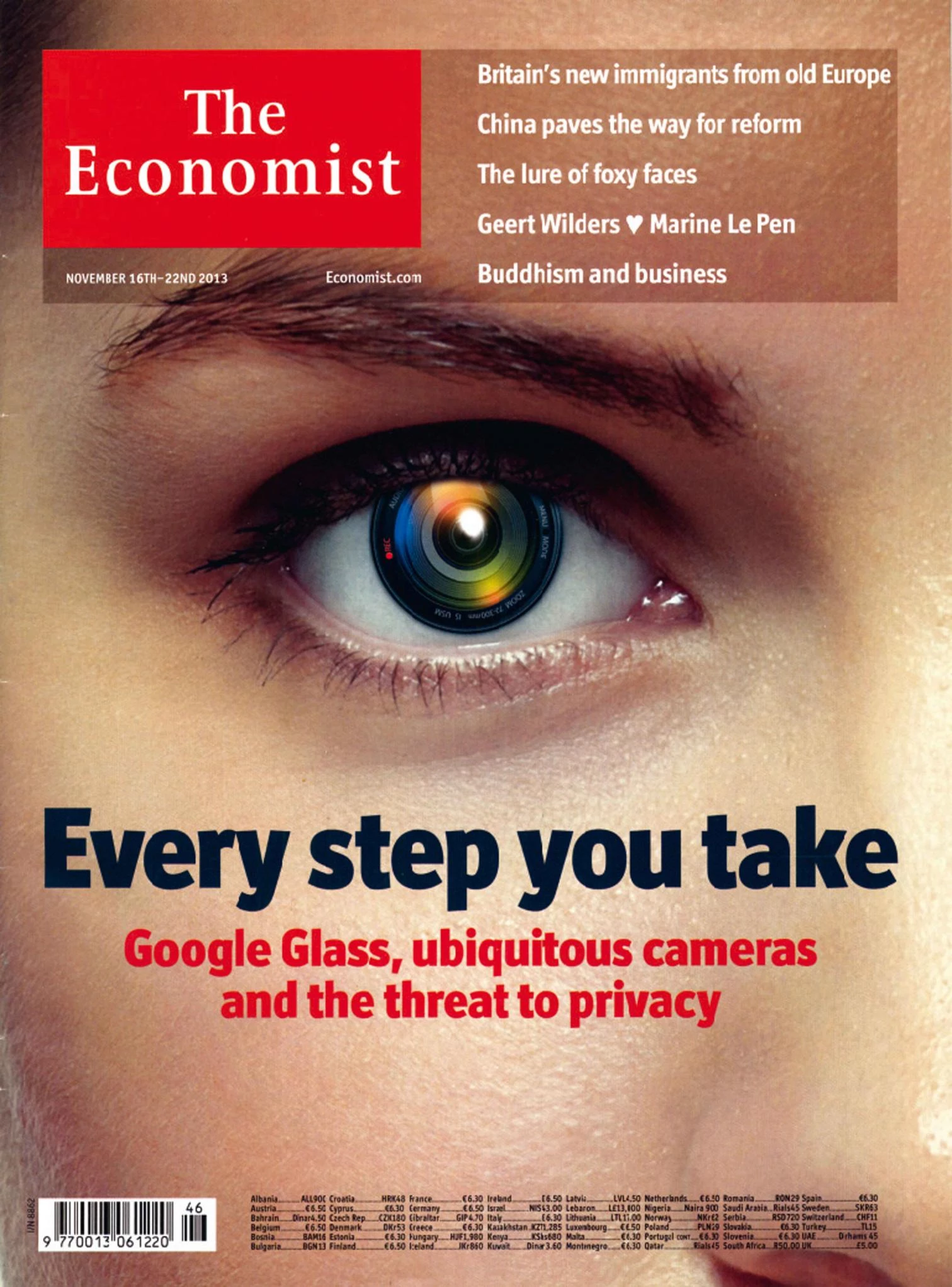

The information boom we call Big Data has entangled the globe in its webs, and both the proliferation of cameras and the overbearing digital presence of the ‘seven sisters’ puts everyone’s privacy at risk.

In fact, no political or social pact can be reached with full transparency. Bismarck sensibly warned that it is better not to know how sausages and laws are made, and the massive leaks of information by Julian Assange or Edward Snowden are not likely to be entirely beneficial, nor their authors unblemished heroes. For their part, the mail and telephone violations of olden times have been replaced today by the digital processing of the information contained in social networks and data bases of corporations or public archives, and the unstoppable proliferation of mobiles and cameras has turned all of us, as in the TV series, into ‘persons of interest’.

This explosion of information, commonly described as Big Data and characterized by the volume, speed, and variety of the data to be handled, has given protagonism to the companies that generate and manage them. Half a century ago we spoke of ‘seven sisters’ to refer to the seven large companies that dominated the oil industry, and through it the global economy, but the oil that drives the world today is information, and the new seven sisters go by the names of Amazon, Apple, eBay, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, and Twitter.

Against them, but with their help, young people in many cities of the West protest wearing the mask of Guy Fawkes, a Catholic conspirator of the 17th century, and this smiling face that hides their features ought to produce as much unease as Ku Klux Klan hoods – or the balaclavas of terrorists and special forces – because the festive atmosphere is ill-suited to any association with one who wanted to blow up the House of Lords. Democratic protest cannot remove private identity from the public sphere, and anonymity on the streets or the web is as censurable as the face-concealing of a police helmet or a Muslim burka.

The confusion between the intimate and the public is such that the same people who demonstrate or control crowds while hiding their identity are willing to show their private life urbi et orbi. Today we no longer need a Limping Devil to raise the roofs of houses to bare their secrets, when those in them already expose their lives in social networks and the media, while public affairs concerning all of us are ambushed in a maze of irrelevant or excessive information. We may have to resign ourselves to the idea that the private citizen’s reserve or modesty is a thing of the past, and that technology has made us as see-through and fragile as the Licentiate Vidriera. With skeptic realism we must also perhaps concede to a certain degree of opacity in power, which is tolerable if it can provide prosperity and liberty with equanimity.

Our ideal of domestic bliss is indeed the introverted precinct, the classical ‘hortus conclusus,’ but we live in the Google showcase, exposed to the abrasion of the traffic of networks and with no other ‘panic room’ than disconnection. In the same way, we dream of transparent parliaments, and when these have had to be housed in historic buildings – such as Berlin’s Reichstag –, architectural debate has revolved around opening them to the vigilant gaze of citizens, but lawmakers, like governments and courts, are in truth as opaque behind glass as behind a wall. While we remain lost between the walled garden and the media showcase, rebuilding the sense of responsibility of the elites will be as important and urgent as regulating the transparency of power.