If there is anywhere that can be seen as the ground zero of what has become the world’s dominant industry, it is Silicon Valley. The place is, of course, a figure of speech, rather than an actual city with a government and a tax base. Nevertheless, it describes an area that has had an impact on the world’s culture and its economy to match that of any city in the last fifty years. It has attracted the talented and the ambitious from around the world; it has created new forms of workplace, new patterns of commuting; and it has accelerated the rate of change.

Beyond the two freeways that form a long, thin rectangle between San Francisco and San Jose is a string of little towns which constitute Silicon Valley and which barely existed in the 1950s. This can be understood as a city not because of its manufacturing capacity (the chip factories are elsewhere), nor for its size or form of government, but because of the people that it is able to attract, a factor that became self-reinforcing when the first generation of computer companies emerged from their garages. Apple, Google and Facebook are all here. Uber and Airbnb, which are transforming transport and hotelkeeping, respectively, are not far away, along with LinkedIn and Twitter. The world has come to look and learn, just as the world went to explore England’s industrial cities at the start of the 19th century.

If Silicon Valley has a centre, it is Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, named, in 1885, in memory of the only son of Governor Leland Stanford and his wife, Jane. And close by, on Sand Hill Road Drive in Menlo Park, is its financial centre, where the venture capital funds cluster together. Stanford was built on the 8,000 acres of farmland that the family donated. Frederick Law Olmsted laid out the campus and it developed in a uniform mission style, with sandstone walls and red roof tiles.

Stanford now has 30,000 students and staff, 14 square miles of nature reserves served by a ring road, called Campus Drive, which connects it to the two freeways that are the main arteries of Silicon Valley. It has nature reserves, a golf course and its own particle accelerator. William Hewlett and David Packard, Stanford graduates in the 1930s, were the first to start a high-tech business in a garage in Palo Alto. Yahoo, Sun Microsystems, Netflix, LinkedIn, eBay and a score of other successful enterprises are linked to the university. Larry Page and Sergey Brin did the early work that made Google possible on campus and gave the university shares in the new company to license the intellectual property. Stanford is the kind of institution that every ambitious city in the world would like to replicate. When he was Mayor of New York, Michael Bloomberg tried to persuade Stanford to set up a second campus on Governors Island in the middle of the East River. In Britain, Cambridge comes closest to Stanford’s remarkable record in turning out graduates who have put their academic training to use to start businesses that have achieved worldwide dominance, apparently instantaneously.

A Network of City-States

Stanford’s presence has made Northern California home to some of the world’s richest corporations, and they in turn have made the university wealthy. Apple, which reached a market capitalization of $900 billion at the end of 2017, making it worth more than the GDPs of Switzerland, Nigeria and Poland, among many other nations, is based in Cupertino. Google is in Mountain View. On a good day, getting to Google by car from One Infinite Loop, Apple’s headquarters, takes just six minutes. Google knows more about us than the US National Security Agency (NSA) and the UK Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ). It has worked on everything from self-driving cars to contact lenses that can monitor blood sugar levels for diabetics. Google can tell us exactly how long a drive will take before we have even started. Menlo Park, another 16 minutes on US 101 heading westward, is home to Facebook, which has more people logging on each day – which is to say, using its products – than the entire population of China.

Apple, Facebook, Google and, up in Seattle, Amazon, are city-states, with no democratic pretensions. They are oligarchies that famously feel no obligation to pay taxes. For Italy’s city-states, there were some sort of checks and balances between civic and religious authority, between pope and emperor. In Silicon Valley, there are no balances. It is the home of a cluster of global superpowers, the product of vertiginous growth, answerable only to themselves, and yet they depend on the wider city-region of which they are part, just as Florence and Siena depended on the wider Italian context for their culture, identity and security.

The total population of the Bay Area is scattered across eight counties and amounts to around 7 million people. This is the kind of urban soup that I once described as The 100 Mile City, where pockets of traditional urbanism float among open country, sprawling business parks and vast transport depots. It has within it one or two components that would be recognized as cities by European standards: San Francisco and Oakland. San Francisco, with about 850,000 people within the city limits, is the most densely populated big city in the United States. It has a downtown and a pedestrian life, as well as one of the USA’s most visible groups of homeless people. A long stretch of Mission Street with its flophouses and street sleepers is precisely the area where tech start-ups have been looking for space for their offices. San Francisco is full of the things that are conventionally associated with urban life: pavements, pedestrians, bookshops, an opera house, Chinese street food and public transport. Oakland, with rather fewer inhabitants, is similar. San Jose looks a lot less like a traditional city, being green, low-rise and low-density, but after decades of steadily expanding its borders it claims to have more people within its jurisdiction than San Francisco.

The Origins

If people work in Silicon Valley, they do not necessarily live there. Commuter buses taking Google programmers out to Mountain View used to come under attack from the more radical of San Franciscans. And the money made in Silicon Valley has had a big impact on property values in San Francisco’s residential streets. Over the past six decades, Silicon Valley has been through successive iterations, the first of which was the research phase, when Xerox shipped over some of its best brains from the freezing winters of Upstate New York to Palo Alto. They were accommodated in the purpose-built Palo Alto Research Center, Xerox PARC. This is where the early work was done on what would become the graphic user interface (or GUI) that opened up computing to the wider world when it was commercialized by Steve Jobs.

Xerox’s scientists and the early technology companies found themselves sharing Northern California with hippies and Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog types. Brand was a key figure in the crossover between the worlds of technology and the counterculture that was to inform Steve Jobs and later Sergey Brin and Larry Page at Google. Brand once lived on a boat moored in Sausalito, just across the Golden Gate Bridge from San Francisco. Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, non-fictional account of Ken Kesey’s LSD-fuelled road trip in search of the Grateful Dead, Hells Angels and Timothy Leary, portrays Brand at the wheel of the magic bus full of Merry Pranksters. Brand published the Whole Earth Catalog; it was an analogue ancestor of Wikipedia, and carried the subtitle ‘Access to Tools’, which went from solar panels to geodesic domes, emerging VCR technologies and self-sufficiency. The 1969 edition had a cover image of Earth as a blue disc in swirling cloud, in stark contrast to the deep black void of space. Here was Buckminster Fuller’s Spaceship Earth brought to life.

Brand played an important role working with Douglas Engelbart, the engineer credited with the invention of the computer mouse, hypertext and email. This cross-fertilization between utopian speculation, physics and mathematics, and between self-reliant autonomy and wealth creation, is what has shaped the urbanism of Silicon Valley. It is a view of city life that is based on a mix of the utopian and the brutally unsentimental, in which the pace of change is continually accelerating, in which all apparently public space is private under the watchful gaze of constantly swivelling surveillance, and where the corporation has commandeered the individual employees’s life and leisure with constant connectedness and the Apple watch has become a symbol of servitude. Three of the four most powerful and richest corporations on the planet have built themselves prodigious new headquarters in the area that we pay as much attention to as Engels and Schinkel gave to Manchester and its mills.

Corporate HQs or Teen Parks?

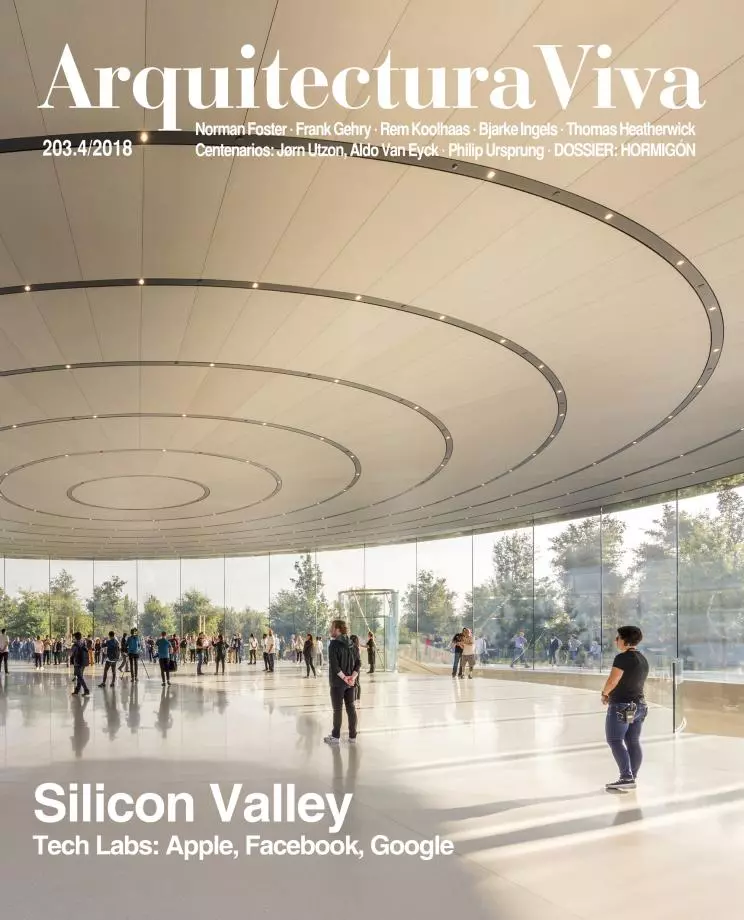

Steve Jobs made one of his last public appearances in Cupertino’s community centre to argue for Apple’s new heaquarters. Cupertino imposed a blanket 45-foot height limit on new developments and had declared itself full. But Jobs got his way. Norman Foster, in close dialogue with Jobs, and then after Jobs’s death with Apple’s best-known designer, Jony Ive, gave the building the form of a continuous ring. It accommodates an astonishing 16,000 people.

In contrast to the anomie and fragmentation of Apple's old headquarters in Cupertino, the Foster building is a single bold gesture on a huge scale which creates a piece of city with a clear identity.

If scale is one aspect of the Silicon city-state, rapid change is another. By local standards Apple is a mature, long-established business. It has been in Cupertino since the earliest days, when it emerged from the garage in which Jobs and Steve Wozniak first started thinking about computers in 1976. But in the six years between 2009 and 2015 Facebook grew even more rapidly than Apple and has occupied four different headquarter buildings. It moved from an office in Palo Alto to a building on the Stanford science park, and then acquired what had been the 1 million square feet that Sun Microsystems had built for itself in Menlo Park, big enough for the 6,000 staff it was employing by 2012. And then Zuckerberg hired Frank Gehry to design the world’s largest room. It is a measure of the speed of change in Silicon Valley that industrial empires, which would once have taken several lifetimes to build, now explode and crumple there as quickly as a smartphone becomes obsolete.

On what was the Sun Microsystems complex in Menlo Park, Frank Gehry has built for Facebook a randomly designed headquarters featuring the world's biggest work room, with space for 2,800 employees.

Like Google, Sun Microsystems was the product of a couple of Stanford graduate students. Started in 1982, it had 38,000 employees around the world by 2006. Four years later it had vanished. Zuckerberg bought the building when the company was sold to Oracle in 2010. Zuckerberg’s designers from a firm called Gensler treated a building that had won awards for its environmental efficiency when it was completed in 1996 as if it were an industrial dinosaur from the steam age. The driving principle for Zuckerberg was to have people work together in unplanned random interactions. Sun had planned their building around what it called an ‘internal street’. It’s the same metaphor that the Gensler team brought to the project. But Zuckerberg’s staff moved into a building that looked as if it had been occupied by upmarket squatters: there is graffiti art, installations, recycled furniture, and the annoyingly teenaged message ‘Move Fast and Break Things’ on the slogan-filled walls. By contrast, when IBM was in its pomp in the 1960s, walls were filled with Paul Rand’s elegantly crafted suggestions that demanded ‘THINK!’.

Facebook moved beyond its retro-fitted home in what was once Sun Microsystems’s building in Menlo Park into a sprawling studio space designed by Frank Gehry that allows Zuckerberg to sit in the middle of what looks like the largest room in the world, surrounded by 2,800 of his employees.

Google, based over in Mountain View, has considered a variety of expansion plans, first with what would once have been the obvious mainstream firm of NBBJ, which specialized in American corporate architecture, and more recently with the unstable pairing of the hyperactive Danish architect Bjarke Ingels and the British designer Thomas Heatherwick.

While Cupertino gave Apple permission to build its new HQ, Mountain View initially took a tougher line. It did not want to see itself turning into a single-company town. The Ingels/Heatherwick project was for a notional 2 million square feet. In consciously unconventional blue-sky thinking, robots that were ‘hackable’ would be used to create endlessly flexible customizable layouts. Google employees would work under artificial skies, giant bubbles that suggested lessons had been learned from Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes. But Mountain View said that it would consent to only 25 per cent of the scheme, and wanted to see LinkedIn take the rest of the space.

These are places that recall the scale of the huge ex-urban complexes of the East Coast that housed the bureaucrats who left New York for the suburbs. But the Silicon Valley behemoths are not cast in the traditional model of buttoned-down business cubicles. These are not offices or call centres, they are hothouses for creative minds. They are filled with brains that need careful nurturing. Those brains belong, mostly, to the young and the narcissistic. They demand in-house cycle repair shops to get their Pinarello fixed. They need beanbags and pizza windows; they need in-house resident artists. They need vegan food and tofu. They need to be able to interact with each other like crazy, all the time.

Foster building for Apple unfavourably with the other Silicon Valley giants’ plans. She sees it as looking back to the days when the big corporations like Union Carbide moved out of Manhattan and into purpose-built office complexes in lush suburban Connecticut, and, shortly after, expired of boredom and irrelevance. But those East Coast offices from the 1960s made a clear distinction between work and leisure, between the company’s time and that of the individual. Facebook and Google attempt to re-create the casual informality of fashionable street life within the compound of a security-controlled environment. They are, in a sense, infantilizing their workforces. They see their lives not in terms of home life but as permanent adolescents. The Facebook HQ is like a college town, without any dorms. In contrast, Foster’s highly polished structure, which is inevitably compared to the industrial design of the company’s products, seems to treat its employees as adults. They are working, not in a Starbucks or the lobby of the Ace Hotel, but in a grown-up building, dedicated to research and creative thinking.

We do not yet know the likely lifespan of the town-sized complexes that Silicon Valley is building. They could vanish even more rapidly than Sun Microsystems. But the big companies now have unprecedented economic power in very few hands. This is a place which saw Kodak, with its massive revenues for so many decades and its 80,000 skilled jobs, vanish. No one in Silicon Valley wants to go the same way.

Time-Lapse Urbanism

The usual claim about the Silicon Valley complexes is that they turn their back on the city, and then try to inject the essence of city life into their controlled environments. Over the years they have got better and better at creating the signals that suggest authentic urbanism in the contexts in which they operate. It’s the Disney version of urbanism, which over the years has gone from ersatz for the original to supplanting it. The question that still has no answer is whether the complexes will get better at creating a corporate culture that will save them from going the same way as Kodak.

The old Apple complex in Cupertino carried the unmistakable flavour of the vanilla-coloured blocks of a generic high-tech business park, lost in the endless parking lots that characterize the workplaces of Northern California. They are the appropriately bland expression of the kind of lurking, mildly sinister, late capitalism that could have come from the pages of a J. G. Ballard novel: a world that has apparently turned its back on the complexities and the random accidents of city life. Foster’s building is altogether more ambitious, different in its scale and in its sophistication. It offers the possibility of a piece of a city that might even outlive the corporation that built it.

It is missing something to see Silicon Valley as a place with no past. As long ago as three quarters of a century before Jobs established himself here, it was already attracting remarkable individuals from around the world. Camillo Olivetti, a bright graduate student from Italy, was at Stanford before he went home to start his own company, a century before Google existed. In the early days, Olivetti’s company made typewriters. Then it went on to mechanical calculating machines, and then, in 1959, under the guidance of Camillo’s son, Adriano, Olivetti built Italy’s first mainframe computer.

It is instructive to compare how Olivetti – for decades seen, much like Apple, as the most admired design-led corporation in the world – housed its research teams with the way that Apple does the job. Olivetti’s designers were based not in Ivrea, the company town not far from Turin (not so different from Cupertino or Mountain View), but on the Corso Venezia in the heart of Milan. It believed this was the only way to attract people of the calibre it needed. They were housed in a honey-coloured stone seminary built in the baroque style in 1652 by Francesco Maria Richini. The entrance had an elaborate pediment and cornice and a rusticated base, and was flanked by a pair of caryatids. Across the courtyard there was still a chapel; the archdiocese rented out the upper two floors to the company. Olivetti has long gone, but Corso Venezia is still a handsome and vital piece of the city, thirty years later.

The Silicon Valley model of urbanism has yet to prove its longevity. Until now it has evolved by tearing down what has gone before. It has built an alternative economic model of urbanism that is the very opposite of the Manchester of the 19th century. It has no need of an industrial proletariat – having outsourced it to Asia. The elite are tended to by barmen and chefs, cleaners and chauffeurs, yoga instructors, bankers and lawyers. Silicon Valley is a city that has no need of high-rise office towers, factories or blue-collar suburbs. It is an economy that is based on an unprecedented embrace of speed and change. For the first time in history, new products can sell in their millions over the launch weekend. It is a speed of change that leaves no time for monuments.

But just as the digital explosion has not ended the human need for physical, material objects, from the cult of vinyl records, to books and art, so Silicon Valley leaves a hunger for a more permanent form of city-building, one that leaves the traces of life lived in it, and time passing.

Deyan Sudjic is the author of The Language of Cities (Penguin), from which this article is taken.