The Art of Reality

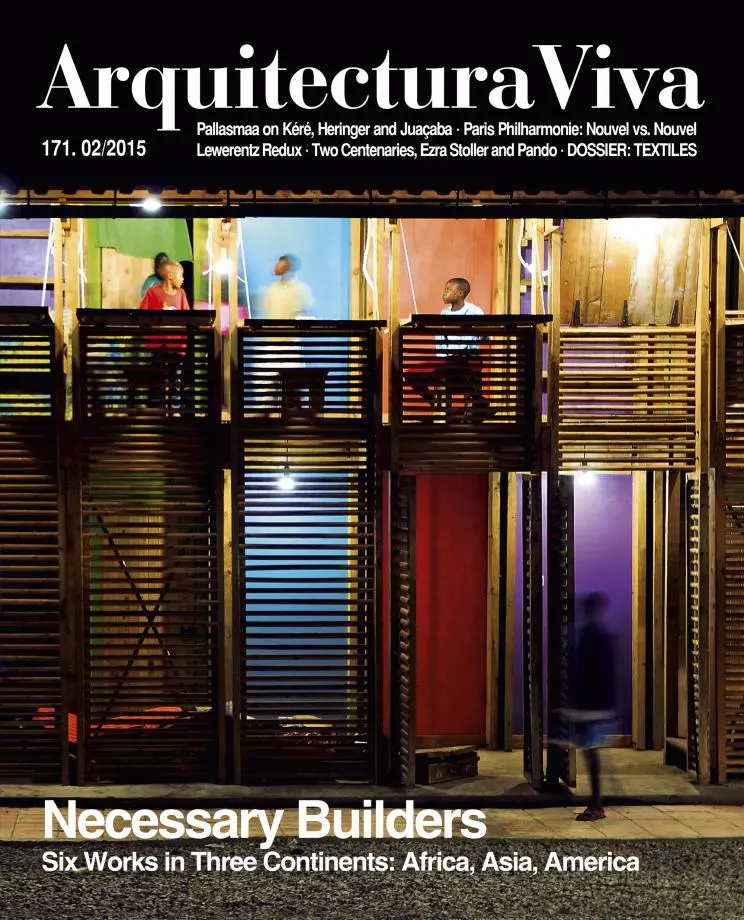

Francis Kéré, Anna Heringer, Carla Juaçaba

In the preface to his best selling novel Crash, J.G. Ballard argues that the relationship between fiction and reality in literature is in the process of being reversed; we live increasingly in worlds of fiction, and therefore the writer’s task is no longer to invent fiction. Fictions are already here, he suggests, and the writer’s task is to invent reality. Isn’t the architect’s task in today’s world of manipulated experiences, desires, and dreams, also to reverse and call for the rediscovery of reality? Already four decades ago Alvar Aalto made the thought-provoking statement: “Realism usually provides the strongest stimulus to my imagination.”

In the industrialized world of wealth, we have been experiencing decades of unforeseen architectural ecstasy and omnipotence; anything imaginable has become realizable. Yet, after the first surprise effect, these formal and structural inventions do not seem to enrich our lives, and the air of heroic newness quickly fades and turns into a feeling of insignificance and boredom. In today’s construction of often limitless material resources and means, obsessive ambitions, competition for visibility, and increasingly autistic expressions, new buildings often seem to take place in a dreamlike, fictitious, and aestheticized world with a weakened sense of causality and reality.

But isn’t the mental task of architecture to articulate and dignify our relationships with our world of experiences? Isn’t the duty of architecture to structure the existential meaning of our daily encounters with the world? As Maurice Merleau-Ponty succinctly puts it: “We come to see not the work of art, but the world according to the work.” Indeed, architecture seems to have entered its own autonomous world that does not mediate and articulate our relations with the realities of life. Buildings of the world of abundance seem to have lost their epic capabilites to connect us with the true narratives of culture, life, and construction.

“Music begins to atrophy when it departs too far from the dance (…) poetry begins to atrophy when it gets too far from music (…),” wrote the poet Ezra Pound in The ABC of Reading. When looking at the alluring buildings of today, I often feel that architecture, too, has forgotten its origins and its very task: establishing the human existential foothold. In my view, architecture arises from the acts of dwelling and celebration. The various diversifications of functions through the evolution of the art of building still echo the primal acts of inhabiting and dwelling. I have learned to value this tradition-bound view of art not as a form of nostalgia or traditionalism, but as the life-force of true renewal, in the sense that T.S. Eliot and Igor Stravinsky famously defined the role of tradition in their crucial essays on the subject.

Due to this alienation of architecture from its existential ground, and drifting into a world of formal aestheticization, devoid of the essential causalities that give buildings their sense of reason, reality, and authority, we find historical and vernacular settings increasingly comforting; they reinforce our sense of the real. These buildings seem to preserve an umbilical cord with the origins, the only thing that can maintain the proper course and provide architecture with meaning, its sap of life. We are beginning to get bored with the new and the unique, aren’t we? Meaning cannot be invented; architectural meaning is existential, and it arises from its live encounter. We desire architectural rootedness and reason; the poetics of humility and reason.

In the past few years, an increasing number of architectural journals have published projects from the non-privileged parts of the world. There have also been conferences and exhibitions dealing with similar issues, such as ‘Architecture of the Essential’ and ‘Edge- Paracentric Architecture’(Jyväskylä, 1994 and 2009), ‘Small Scale, Big Change’ (New York, 2010), or ‘Necessary Architecture’ (Pamplona, 2014), not to speak of growing interest in sustainability. The recent Pan-American Architecture Biennial in Quito awarded a humble bamboo house in a remote area of Ecuador and a horse farm over hundreds of technologically oriented urban projects. In accordance with its task, too, the Aga Khan Award has brought numerous projects from the Islamic world to international attention (in fact both Kéré and Heringer have received this award). In November, the jury of the prestigious Schelling Architecture Prize in Germany chose Diébédo Francis Kéré over the two other finalists, who were Anna Heringer and Carla Juaçaba. These contestants represented parallel approaches to architecture, approaches arising from a sense of the real. The Schelling jury had formulated the theme for the 2014 prize as ‘Indigenous Ingenuity,’ and posed the question: “How can an imaginative and site-specific architecture fulfill basic human needs in a self-explanatory way?”

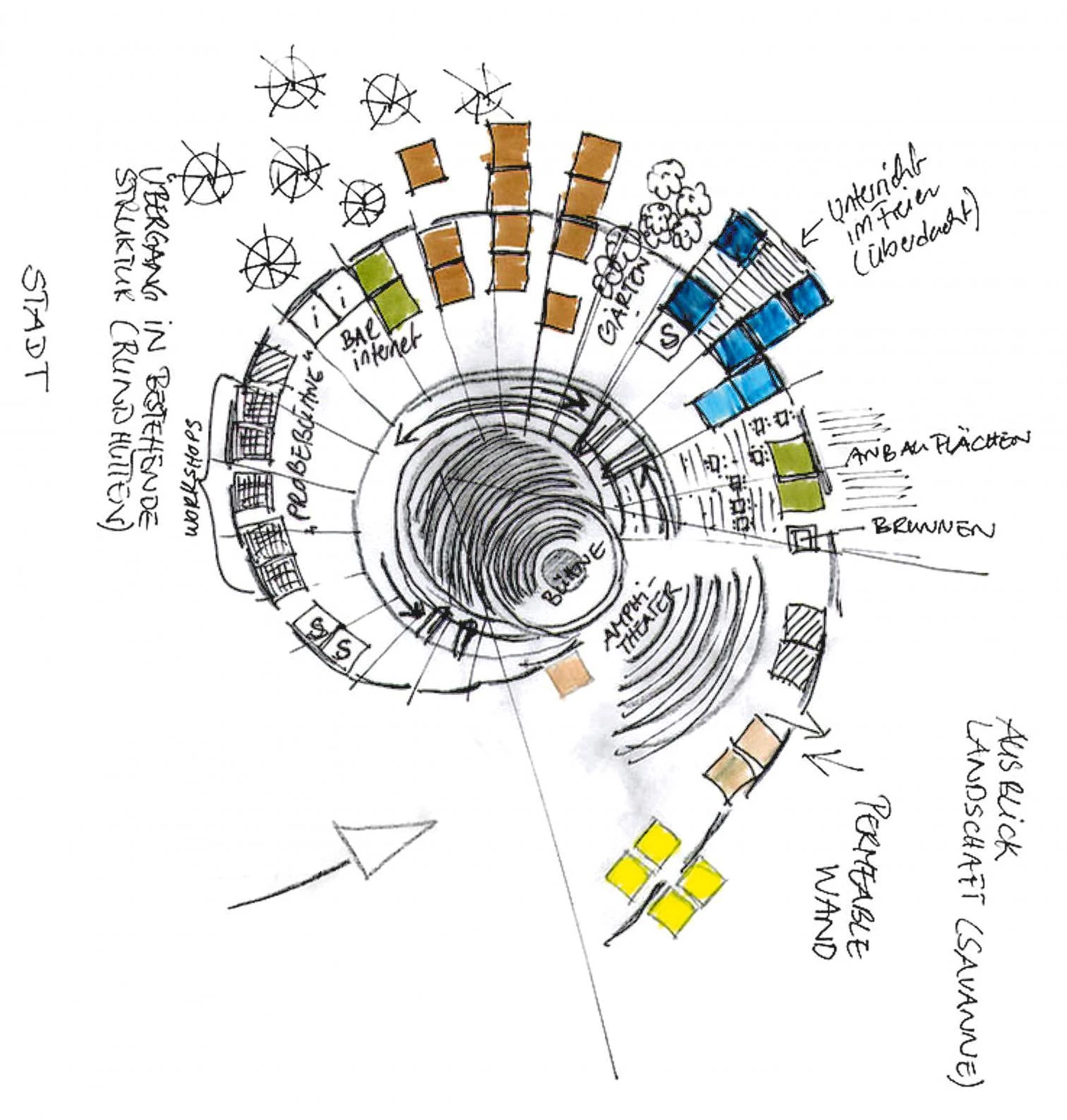

Diébédo Francis Kéré

Diébédo Francis Kéré (1965) has emerged as an exemplary representative and spokesman of an architecture that is engaged with local traditions, craft skills, and materials, and a basically modernist sensibility of volumetric, spatial, and structural design. Kéré’s buildings have the clarity and authority of Le Corbusier’s early houses, inspired by his journeys around the Mediterranean studying vernacular constructions as an alternative to the tired academicism of the time. Kéré grew up as a member of his native clan in Burkina Faso and was the first individual in his village to attend school. He received his professional training as an architect at the Technical University of Berlin, and made a school project in his hometown, Gando, his diploma project, winning the Aga Khan Award after the building was executed.

Since his initial success, he has turned into a fluent cosmopolitan working also in Germany and other countries on projects related to totally different socioeconomic and cultural realities. The strength of his African buildings arises from the acknowledgment of local climatic and socioeconomic conditions, but they are also independent types that can be further elaborated and adjusted to differing situations. He is at once an insider and an observer of the traditions of his land, which is probably what helps him in his un-romantic and non-picturesque approach. Yet, regardless of the autonomy and personal logic of his architectural solutions, his buildings have a strong sense of place, cultural specificity, and emotive ambience. His architecture fuses serious deliberation and reason with a sense of playfulness and joy. This is probably a quality that is part of his mental constitution rather than a conscious intellectual goal. Kéré regards the collaboration of the villagers essential to the success of his projects: “Only those who are involved in the development process can appreciate the results achieved, develop them, and protect them.”

Kéré’s buildings are executed with traditional materials and skills, and they address the specific needs of the communities that raise them, but they never succumb to romanticism or the pretty picturesque.

Kéré mostly uses mud bricks, both in wall structures and in vaulted ceilings with light metal constructions for roofs. He has recently also experimented with the use of clay vessels placed in the vaults to reduce weight, articulate acoustic qualities, and create culturally familiar visual patterns. Clay vessels tie his buildings strongly with local craft traditions.

Kéré’s buildings include schools and health facilities, a library, a National Park, a Women’s Association Center, a Center for Earth Architecture, residential projects, and a Modular Housing Prototype, not to mention projects in Germany, China, and elsewhere.

DESI Training Center, Rudrapur (Blangladesh)

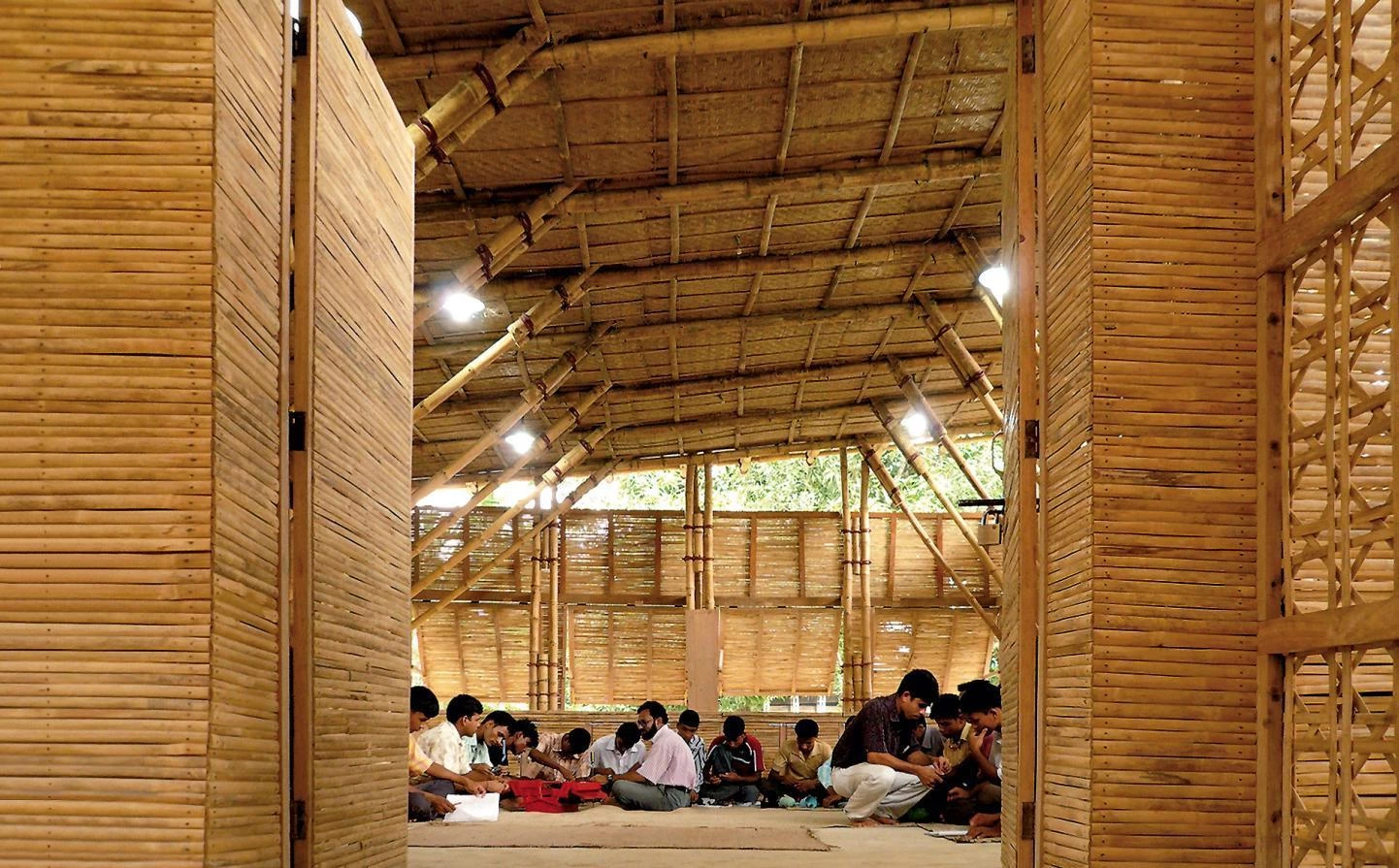

Anna Heringer

The work of Anna Heringer (1977) has also been widely publicized and awarded. She comes from the Austrian-Bavarian border region, but at the age of 19 she lived nearly a year in Bangladesh and became passionately interested in local architecture as well as in traditions, skills, and materials. She designed the Meti School in Rudrapur, Bangladesh, as her diploma project in Linz, Austria. A year later the project was executed and won the Aga Khan Award. Following this initial success, she has built and taught in Europe, Asia, and Africa, and her work has been published and exhibited internationally. Her buildings are usually made of loam and straw for walls, and bamboo as both a structural and an ornamental material. The bamboo brings to mind traditional constructions of the area, but like Kéré’s works, her buildings have a logic and character of their own. Clay is used to create intimate, protective, and tactile spaces on the ground floor, whereas bamboo bridges long spans and creates the climatic shelter. There is a growing interest today in the use of bamboo for structures, furniture, surfaces, and objects. Bamboo is an extremely fast-growing reed, and it is evident that the contemporary use of this material is just beginning.

Heringer’s buildings are based on a convincing technical logic and use of local skills, but though grounded in necessity, they have an elevating, optimistic character. The ornamental motifs and vibrant colors contribute to an air of celebration. In addition to buildings, she has developed textiles based on local traditions.

Carried out in direct dialogue with the local population, Heringer’s buildings give tactile sensations thanks to materials like clay or stone combined with the lightness and permeability suggested by bamboo.

Anna Heringer’s little credo defines emancipatory and empowering qualities of architecture as her ultimate goal. These humane aspirations are also, for her. the foundation of beauty. “The vision and motivation behind my work is to explore and use architecture as a medium for strengthening cultural and individual confidence, supporting local economies, and fostering the ecological balance (…). For me, sustainability is a synonym for beauty; a building that is harmonious in design, structure, technique, and use of materials, as well as with the location, environment, user, socioeconomic context. This, for me, is what defines its sustainable and aesthetic value.” Indeed, sustainability can hardly become accepted in today’s world merely as a technical goal. Sustainable aspirations have to be turned into a desirable new lifestyle and internalized ethics and be experienced as a new kind of beauty.

Carla Juaçaba

Carla Juaçaba (1976) has worked since 2000 as an independent architect. She is known for her formally simple but emotionally intense designs for houses, such as Casa Bonito (2005), Casa Varanda (2007), and Casa Minima (2008). These houses were conceived as formally abstracted schemes, contrasting heavy masonry walls with hovering steel/wood floor and roof structures. Abstraction and formal reduction are juxtaposed with stone walls that become metaphors of nature, time, age, and gravity, and bring a sense of rootedness, stability, and place.

Her largest project to date is the Humanidade Pavilion for the second UN Conference on Sustainable Development in 2012 (with artist Bia Lessa), on the site of a historical fort in Rio de Janeiro. The pavillion was an ephemeral, translucent scaffold structure that housed the various functions of the event, supported by five structural scaffolds. The volumes floating in space suggested Freedman’s utopian urban visions of the 1950s and 1960s. In accordance with the pavilion theme, sustainability, it was built with a standard construction scaffold system with other easily available materials, and after dismantling, it was completely reusable.

Author of small houses and large pavilions, Juaçaba has developed a unique language where recourse to sustainable materials and techniques is combined with a rigorous and stripped formal language.

Juaçaba’s work aspires to elegance, sensuality, experiences of contrasts; levitation and gravity, abstraction, a sense of the real. Her exhibition designs project a sense of weightlessness and immateriality, as exemplified by the Isostasy installation held together by magnets.

Juaçaba’s oeuvre is not directly engaged with social issues, but in its focus on formal reduction, purity of expression, and deliberate interest in sustainability, her work exemplifies an ascetic and poetic architecture that projects an aesthetic and ethical air. Regardless of its abstractness, her work reflects the virtuoso spirit of Brazilian modernity. There is also a touch of the rationalism of the Californian Case Study Houses of the 1940s and 1950s in the orderly elegance of her houses.

A century ago, modern music, painting, and sculpture sought inspiration for radical artistic experimentation in folk music as well as primitive and naive art. At the same time, many of the architects of early modernity were influenced by traditional and vernacular architectures; the worldwide influence of traditional Japanese architecture was particularly important.The architectural structuralism of the 1950s and 1960s sought inspiration in anthropological studies and especially sub-Saharan and North African building traditions. Have we again, after several decades of vision-centered and aestheticized architecture, come to a point where we can use guidance from cultures of reality and need? I believe that we need to re-identify the primary purposes and evolutionary roots of architecture.