Architecture is a hybrid and ‘impure’ discipline which, instead of being grounded in its own independent theoretical foundation, largely relies on the theoretical views of other areas of research and knowledge, The practice of architecture fuses ingredients from conflicting and irreconcilable categories: materiality and feeling, construction and aesthetics, physical facts and cultural beliefs, knowledge and dreams, past and future, means and ends. In the past decades architecture has been viewed from various theoretical perspectives provided by psychology, psychoanalysis, structuralist linguistics, anthropological studies as well as deconstructionist and phenomenological philosophies. On the other hand, the fast development of computerized digital technologies has provided an entirely new horizon for architectural production.

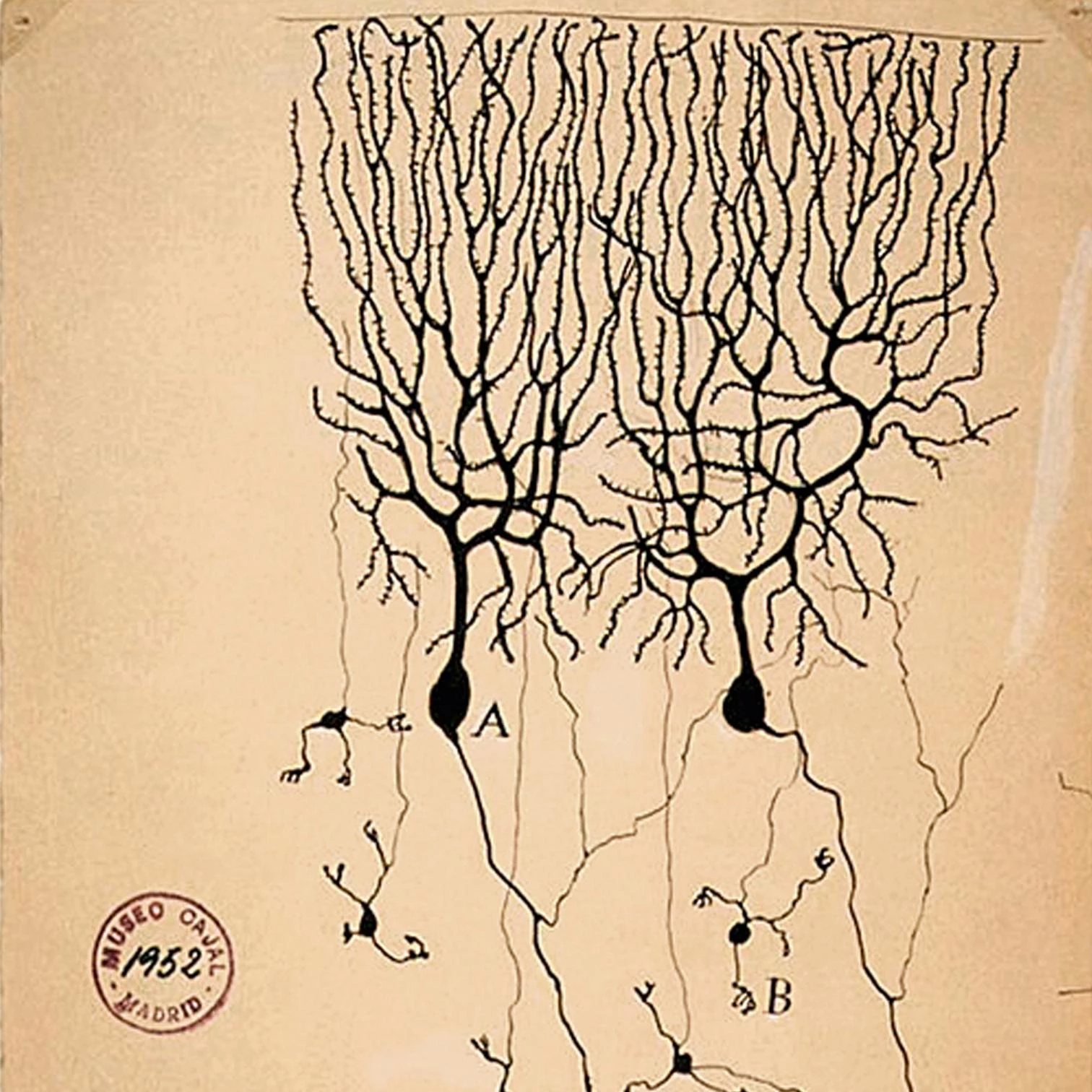

Along with the currently popular discourse arising from ideas of human embodiment and the emphasis on experiential qualities, findings and views emerging in the neurosciences promise a deeper understanding of the mental implications and impacts of the art of building. Findings on the complexity and plasticity of the human brain and neural systems emphasize the innately multisensory nature of our existential and architectural experiences. These views challenge the visual understanding of architecture and suggest that significant architectural experiences arise from existential encounters rather than retinal percepts. The discovery of mirror neurons helps us understand the origins of empathy and how we can experience emotion and feeling in spatial and material phenomena.

Scientific experiments reveal the processes taking place in the human brain as well as their specific locations, dynamics and interactions. Yet, experiencing mental and poetic meanings through space, form, matter and illumination is a phenomenon of a different category and order than observations of activities in the brain. So combining the quickly advancing neurological knowledge to appropriate philosophical framing and analyses seems a particularly suitable methodology in approaching the mysteries of artistic meaning. This approach with a double focus can be appropriately called neurophenomenology.

Growing interest in the neuroscience of architecture has led to the establishment of the Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture (ANFA) in San Diego. In addition to research projects, the Academy hosts conferences on aspects of the neuroscience of architecture. In November 2012 the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture and the Academy organized the pioneering conference ‘Minding Design: Neuroscience, Design Education and the Imagination’, which brought together scientists and architects.

Interaction of neurosciences and architecture offers potentials for enhancing our settings. Any scientific proof of mental phenomena and their consequences concerning our environments will help make claims for architectural qualities that are more acceptable in our materialist culture.This conversation is in its beginnings and is largely directed by neuroscientists. Yet neurologist Semir Zeki has made the strong claim that great artists have always been neurologists in intuiting how the human mind works and how to excite it through poetic images. In Proust was a Neuroscientist Jonah Lehrer argues that Walt Whitman, Marcel Proust, Paul Cézanne, Igor Stravinsky and Gertrude Stein anticipated certain neurological findings of today in their art. Obviously the neuroscientific investigation of architectural experiences and meanings has to be based on a dialogue between scientists and the makers of architecture.