Architecture and art make strange bedmates. In contrast to the seamless continuity of classicism, modern severeness introduced a wedge between the abstract rigor of a building and the emotional fervor of the arts. In rejecting ornament, architecture refused to don the accessories of the so-called minor arts, and by asserting its autonomy, loosened its historic ties to sculpture and painting. The postmodern counter-reformation limited itself to chanting a mea culpa for the dogmatic excesses of modern fundamentalism, and its nostalgic call for a return to premodern attachments only took hold in the commercial sphere of thematic representation. Nowadays, architecture and art eye each other with curiosity and skepticism, while exploring divergent modes of coexistence. As far from the impassioned fusion advocated by the Gesamtkunstwerk as from the indifferent, reclusive divorce declared by the moderns, the experimental and roving promiscuity of our times speaks of an architecture that does not marry art, but will neither make a vow of chastity. Rather, architecture and art live side by side in uncertain adventures, with variable results.

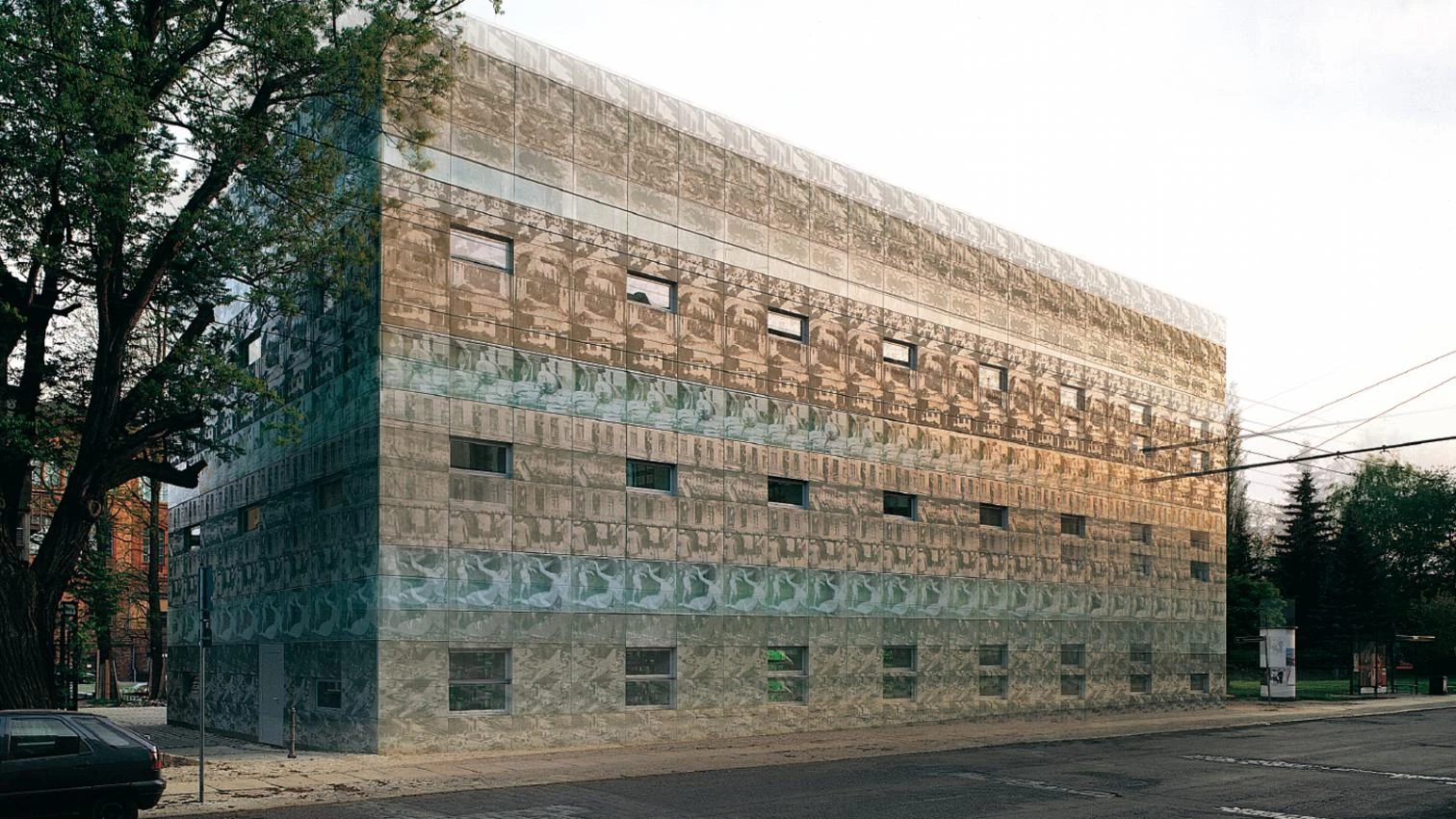

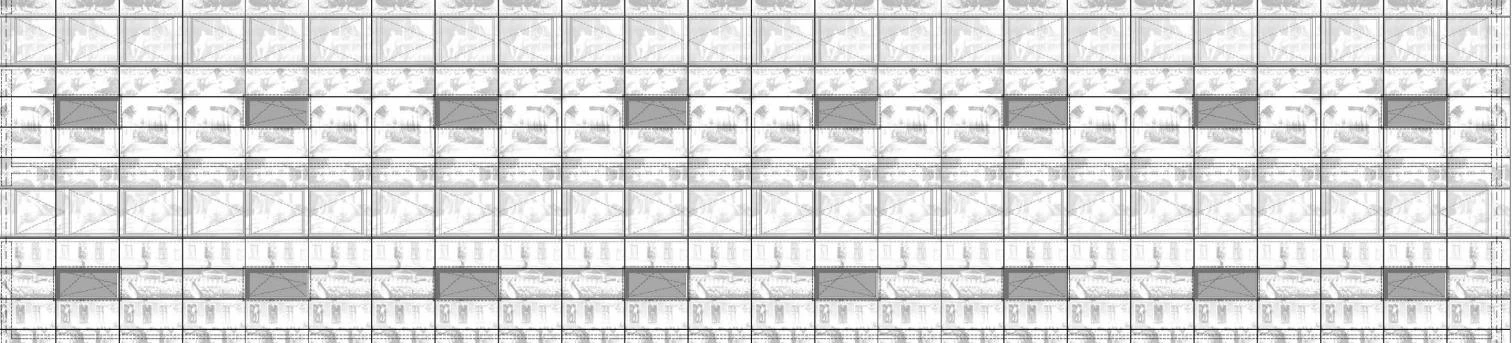

The facade of the Eberswalde university library, designed by Herzog & de Meuron, physically supports the vision of German culture and history reflected in the images selected by artist Thomas Ruff.

Michelangelo, Siloé or Bernini would have considered collaboration between architects and artists a redundance. To them there was no caesura between sculptures and buildings, and their work would have fully satisfied the demands of the contemporary cynicism that augurs excellent results for such collaboration... whenever architect and artist are one same person. Modern architecture limited itself to the art of the counterpoint, using its expressive density to emphasize, by way of contrast, the silent abstraction of its volumes. The organic presence of Kolbe’s feminine figure in Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona pavilion highlights the geometric exactitude of an exquisite and mineral space, but does not engage in an egalitarian dialogue with architecture. The same can be said of the sculptures by Henry Moore, Calder or Chillida which have in the second half of the century flourished before the impassive prisms of institutions and corporations: modern orthodoxy needed the garnish of a Miró mural, an Oldenburg piece or a Noguchi garden.

Architecture and art try new forms of dialogue: Francesc Torres built his Verneda line in a popular area of Barcelona (below) while Cristina Iglesias designed a fountain for the Amberes’ Museum of Fine Arts (above).

In the past decades, architecture has recovered the taste for conversation with the world of art, which it no longer looks at as a mere supplier of monumental ornaments, but as a landscape of formal and perceptional experiences that can fertilize its autonomous exploration of construction. The constant dialogue between Frank Gehry and Richard Serra – which has been going on for twenty-five years and had the chance to be captured, in all its grandeur, in the recent exhibition at the Guggenheim Bilbao – wonderfully exemplifies this new attitude. This takes on a variety of forms and methods, and some of the more characteristic ones are present at the Madrid gallery of Elba Benítez, where five experiments involving the collaboration of architects and artists – strung together by a common desire to blur the limits of disciplines and authorships – mark the lines of a vast territory that ranges from urban design and gardening to construction and interior decoration.

At the far ends of the scale are the two most narrative projects, whose controversial temperatures tense up the thin skin of the exhibition, each weaving a historical text on the physical grid of the city or building, as the case may be. The Línea de la Verneda, a project of the New York-based Catalan Francesc Torres in conjunction with architects of Barcelona’s Town Hall, is a slender band of steel, concrete and resins that stretches along the 1,500 meters of a new boulevard in a popular part of the Ensanche, disappearing into the ground at each intersection to reemerge and resume its abbreviated narration of the quarter’s history. A collective memorial and visual poem in the manner of Joan Brossa, this work of Torres is a metaphor of the discontinuity that characterizes a biography’s mark on the world, a testimony of its commitment to the identity of voiceless communities, and a tribute to his personal transit from the installation to the story, so clearly manifested in the laconic prose of his latest book, The Repository of Absent Flesh.

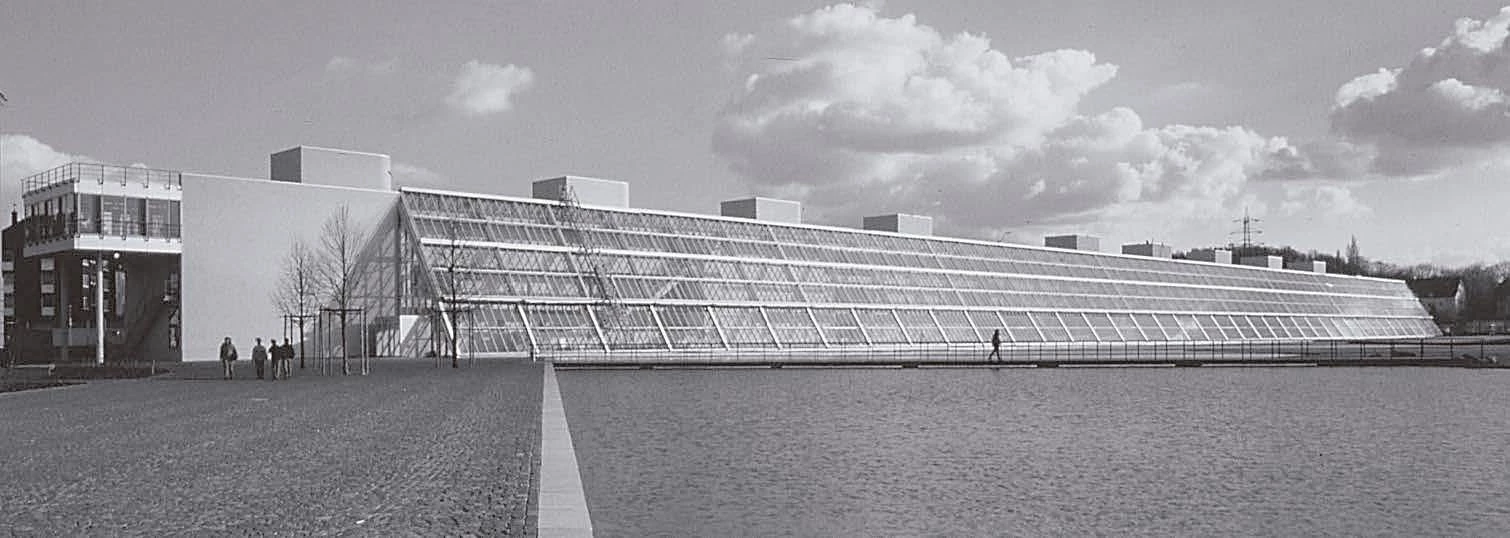

Dan Flavin’s luminous installation for a building by Uwe Kiessler in Gelsenkirchen (above) and the Garden of Waves by Fernanda Fragateiro and Joâo Gomes da Silva in Lisbon (below) complete the list of examples.

A library at Eberswalde – a small village near Berlin – is the fruit of the collaboration of the Basel architects Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron with the Düsseldorf artist Thomas Ruff, who used press clippings and his own photographic archives to create the iconography of the building’s unique facade of glass and concrete, where references to German history are skeptically interwoven with images of cultural or scientific themes. By serigraphing the images on the bands of glass and lithographing the concrete through formwork with sheets that use setting retarders instead of ink, the architects came up with a fascinating, textile-like continuum of materials enclosing the prism of the library, whose volume dissolves in the vibration of the skin’s repeated tattoo. With echoes of Warhol’s ironic serializations, but more powerfully evoking the mosaic murals of architect and painter Juan O’Gorman’s university library in Mexico City, this is a masterly example of the new age of collaboration between architects and artists, and a major work of the Swiss partners, whose brilliant record of exploring forms has few equivalents among their contemporaries. Jacques Herzog has said that their work is so artistic precisely because it is very architectural, and it might be true that collaboration is not so much a matter of approaching the alien as it is of going deeper unto one’s own, and that the best basis for dialogue is introspection.

The exhibition at the Elba Benítez Gallery includes projects of markedly different natures and scales, ranging from the landscaping of Lisbon’s Expo or the gardens fronting Antwerp’s Museum of Fine Arts to the lighting of one of the buildings of the world’s fair at Emscher Park, on the basin of the Ruhr. For Lisbon, architect João Gomes da Silva and artist Fernanda Fragateiro created a lyrical Garden of Waves as a recreational space for visitors to Expo 98, in the form of a meadow whose gentle undulations evoke the waves of the Tagus River’s banks. In Antwerp, the sculptress Cristina Iglesias worked with the architects who designed the surroundings of the Fine Arts Museum to build a reflecting pond whose bottom is a fascinating bas-relief of vegetal forms, and whose regular filling and draining will make it alternate between a mirror and an abyss. And in Gelsenkirchen Dan Flavin left one of his final works, a peer of his lighting fixtures for the Calvin Klein boutiques in New York, Tokyo, Seoul and Zürich, and which here is a luminous installation in the glazed atrium of an office building erected by the architect Uwe Kiessler, its horizontal form beside a small lake stressed by the artist’s characteristic fluorescent lights.